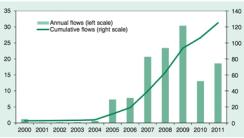

According to the UN’s 2012 World Investment Report , sovereign funds are increasingly important contributors to foreign direct investment (FDI), allocating roughly $125 billion today with a trend-line that suggests this will increase dramatically in the years ahead. I think this is a pretty big deal. And to explain why, let’s start with some FDI 101.

The IMF defines ‘foreign direct investment’ as a category of international investment whereby there exists “a resident entity in one economy (direct investor) with the objective of establishing a lasting interest in an enterprise resident in an economy other than that of the investor (direct investment enterprise).” Importantly, “lasting interest” refers to a long-term relationship in which the direct investor holds a certain amount of influence over the management of the direct investment enterprise. As such, FDI is quite different from funds’ standard portfolio investments in public equities. Foreign direct investment is akin to ‘foreign direct influence’ over local private enterprises. In general terms, we would categorize an investment as being “FDI” once an equity position passes 10%. (If you’re still not sure what it looks like to have a SWF influencing management decisions, have a look at the ‘fun’ Glencore and Xstrata are having with the Qatar Investment Authority .)

Anyway, here’s a useful blurb from the UNCTAD report describing the FDI that SWFs are making:

“FDI by SWFs is concentrated on specific projects in a limited number of industries, finance, real estate and construction, and natural resources. In part, this reflects the strategic aims of the relatively few SWFs active in FDI, such as Temasek (Singapore), China Investment Corporation, the Qatar Investment Authority and Mubadala (United Arab Emirates).”

So that’s the scene. Now, why do I think this is a big deal? Two reasons:

1) This is precisely the kind of investing that I (personally) like; investors seeking to add value to portfolio companies through active engagement ( see AIMCo as an example of what I'm talking about); and

2) This is precisely the kind of investing that Western policymakers freaked out about in 2008, leading to the (seemingly dormant) International Forum and the ( well intentioned but flawed ) Santiago Principles.

In short, the trend towards more FDI by SWFs will inevitably raise some eyebrows among policymakers in target countries. But that’s not to say that SWF FDI should be avoided or even discouraged. In fact, this type of investment could serve as a catalyst for economic growth by building required infrastructure or developing agriculture. And UNCTAD has some interesting perspectives on how this can be achieved:

“As SWFs become more active in direct investments in infrastructure, agriculture or other industries vital to the strategic interests of host countries, controlling stakes in investment projects may not always be imperative. Where such stakes are needed to bring the required financial resources to an investment project, SWFs may have options to work in partnership with host-country governments, development finance institutions or other private sector investors that can bring technical and managerial competencies to the project – acting, to some extent, as management intermediaries.

“SWFs may set up, alone or in cooperation with others, their own general partnerships dedicated to particular investment themes – for example, infrastructure, renewable energy or natural resources. In 2010, Qatar Holding, the investment arm of the Qatar Investment Authority, set up a $1 billion Indonesian fund to invest in infrastructure and natural resources in Indonesia...”

“Where SWFs do take on the direct ownership and management of projects, investments could focus on sectors that are particularly beneficial for inclusive and sustainable development, including the sectors mentioned above – agriculture, infrastructure and the green economy – while adhering to principles of responsible investment, such as the Principles for Responsible Agricultural Investment, which protect the rights of smallholders and local stakeholders.”

In short, UNCTAD believes that SWFs should continue to make foreign direct investments. However, UNCTAD also believes that these sorts of investments should be done in ‘friendly’ and ‘unthreatening’ ways, such as setting up special purpose investment vehicles that ensure de-politicization of the investment process (i.e., a local GP) or investing in industries that have substantial positive impacts on local communities (e.g., infrastructure).

That’s nice in theory. But will it work? Will SWFs pay attention? I don’t know. Whatever the case, it will be rather interesting to watch policymakers react to foreign sovereign funds influencing the operations of local companies in the years ahead...