The Hong Kong Police Force has begun arresting some of the leaders of the civil disobedience movement known as Occupy Central, which virtually shut down key thoroughfares of China’s offshore financial center for almost three months late last year.

At their peak, the demonstrations drew more than 250,000 mostly young people to the streets to protest China’s decision to restrict the field for Hong Kong’s chief executive election in 2017 to candidates approved by a Beijing-appointed selection committee. Many of the protesters called on the current chief executive, C.Y. Leung, to resign. Leung and the government didn’t yield to the protesters’ demands and ultimately enforced court orders to clear the protest camps and reopen the streets by mid-December.

Police have not publicly announced whom they plan to arrest, but, according to local police sources and those close to opposition groups, more than 30 key figures of the movement will be arrested in the coming weeks for “instigating, organizing or aiding and abetting an unlawful assembly” that began September 26 and ended on December 15.

“They are asked to go to the police headquarters to assist in a probe in connection with a case of unlawful assembly,” according to a police source, who added that these individuals would be arrested and then granted bail. “If they fail to come, we will visit them and make arrests.”

Among the 30 or so names, according to the police source, are three leaders who founded the Occupy Central movement: Reverend Chu Yiu-ming and University of Hong Kong professors Benny Tai Yiu-ting and Chan Kin-man. The three men reported to the police in early December, in the dying days of the demonstrations, and were allowed to leave after about an hour. Key members of two student groups that spearheaded the movement also may face questioning and arrest, sources say, including Alex Chow Yong-kang of the Hong Kong Federation of Students and Joshua Wong Chi-fung, co-founder of the group Scholarism.

Authorities have been vague on what kind of penalties the protest leaders may face, but, according to lawyers familiar with Hong Kong law, the punishment could include some jail time. “The police are still investigating at this stage, so we can’t comment on this,” secretary for Justice Rimsky Yuen Kwok-keung told news media recently when asked about possible prosecutions. “I can only say that we will act in accordance with usual procedures, that is, all the relevant information and evidence will be presented to the Department of Justice. The department will decide according to the law and the code of prosecution.”

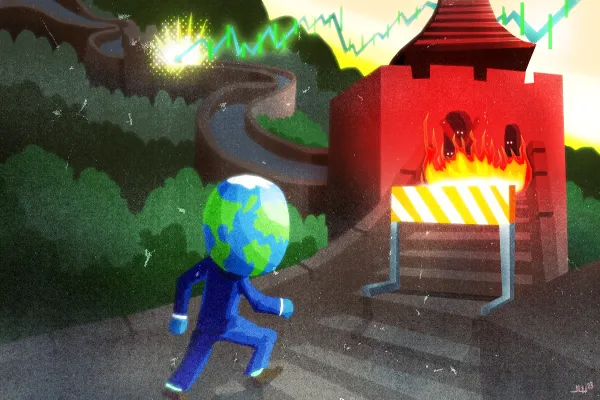

Punishment is likely to be muted because officials are wary of arousing international criticism of human rights restrictions in Hong Kong, which has enjoyed a reputation as a bastion of capitalism and freedom of expression at the doorstep of an autocratic China, says Paul Schulte, who heads his own Hong Kong–based equity research firm, Schulte-Research.

“I think these arrests will fizzle and go away,” Schulte says. “Nothing is served by harsh treatment. That would be counterproductive and would be a blot on an otherwise impressive job that the police did in dealing with the situation. The Hong Kong police are respected internationally for the coolheaded and professional way they handled the situation. They want to keep this reputation intact.”

The protests were the largest to take place in Hong Kong since 1967, when leftist students and union workers led riots against the British colonial government that caused 51 deaths and more than 800 injuries. There were no fatalities during the recent demonstrations, but dozens of protesters and police officers were injured in confrontations. Police arrested more than 5,000 people after the 1967 riots, and dozens were incarcerated for years. The British government also banned leftist newspapers from publishing and shut down schools with left-leaning curricula.

By comparison, Beijing and the Hong Kong government have refrained from taking drastic actions in the aftermath of Occupy Central. So far, no conservative newspapers or schools that were closely tied to the protests have been prevented from operating.

Officials have taken a step recently to address some of the economic issues that helped fuel the protests. In late December the government announced plans for a HK$27 billion ($3.5 billion) housing reserve fund as a first installment of a program to build 290,000 low-cost apartments in a bid to boost the supply of housing and lower the cost of home ownership.

Growing inequality and a severe housing shortage have fed much of the discontent that lay behind the protests. Average real wages rose by just 3.2 percent over the past decade, whereas real estate prices tripled during the same period. Hong Kong had the most unaffordable housing in the world for the fourth straight year last year, according to a survey of 360 cities by U.S.-based consultancy Demographia. The survey found that Hong Kong’s median home price was HK$4.02 million ($516,000), or nearly 15 times the median annual household income of HK$270,000.

Schulte cites a growing public debate about the need for social welfare measures as further evidence that the demonstrations may spur changes in policy. “You see greater focus on what government will pay for in-hospital treatment. You see more attention on the question of payments for the elderly,” he says. “You see people saying that a place as great as Hong Kong can no longer throw its least desirable to the dogs. Some form of welfare is coming, and this is definitely a good thing.”

Still, uncertainty continues to hang in the air, weighing on markets. The Hong Kong stock market is down 4.7 percent since early September and has not recovered, notwithstanding Beijing’s introduction of direct access between the Shanghai and Hong Kong markets in November. Indeed, the performance of Hong Kong stocks has paled in comparison with the mainland market, where the benchmark CSI 300 index soared 62 percent in the last five and a half months of 2014.