Illustration by II

Shock rippled across the asset management world in March when it was reported that Vanguard was pulling out of China. Reports from Chinese news site Caixin, later picked up by Bloomberg and the Financial Times, said Vanguard had planned to scrap its joint venture with Ant Group, a partnership envied by competitors when it was announced in 2019.

It didn't seem to add up. Until that point, the numbers reported by the venture seemed promising. Vanguard said in 2021 that it had secured more than 1 million mainland customers, and by January 2022, the clientele had reportedly swelled to 3 million. This early success signaled the possibilities for others in China’s multitrillion-dollar market.

So when news of the closure circulated, many attributed the flop to outside factors rather than anything the U.S. fund giant had, or had not, done. A limited pool of underlying securities and minimal access to offshore markets had made it hard for the partnership to shine, sources told the Financial Times. The heated race for fund advisory in China was hurting profitability as more players came in, the South China Morning Post said.

Meanwhile, Vanguard denied the rumors. “It’s business as usual for us and our JV in China,” a spokesperson at Vanguard told Institutional Investor in May. “The reports in Caixin and then subsequent media outlets were based on rumors and speculation.” II’s sources initially said the speculation could have originated from a disgruntled former employee before being passed from Chinese media to international outlets.

In October, Vanguard confirmed that the story was true. The manager sold its 49 percent stake to Ant. In a statement to II, a spokesperson said it would “continue to support the joint venture through December 2023. Vanguard will close its Shanghai office thereafter and will continue to monitor developments in China. We have not ruled out other business opportunities in the future.”

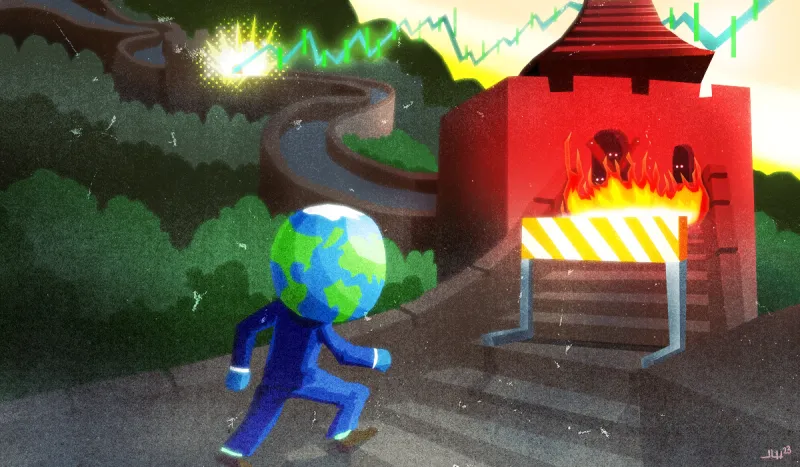

The fact that the departure made such big news illustrates the challenges facing foreign asset managers in China, where the opportunities are plentiful, but so are the obstacles.

“People do not want to say, ‘We did China wrong,’” says Peter Alexander, managing director at investment consultancy Z-Ben Advisors in Shanghai. “And the majority of them did it wrong — they didn’t understand the market, so they are looking for an excuse.” A decision to turn tail by the likes of Vanguard could signify the end of the growth market for asset managers that have been eyeing success in China in the past decade as foreign investment laws have been relaxed. It might have even been seen as a relief by others that have been struggling there. “There would be no better excuse,” Alexander added in a call before the end of the joint venture was confirmed, “than if Vanguard were to exit and they could say, ‘The second-largest asset manager in China couldn’t make it work, we can’t either.’ If Vanguard said they were going to exit, this would give considerable internal political cover for others who want to pull out.”

Foreign asset managers have been slow to crack China because of regulatory caps. Despite reforms, China’s A-shares market is still largely dominated by domestic investors, unlike many developed markets where foreign institutions play an important role. Prior to 2011, foreign ownership in A-shares was below 1 percent. The level has increased slowly since 2016, but by 2018 it was still below 3 percent.

In recent months, investors have been pulling out of China over concerns about the economy and the unfolding crisis in real estate that began in 2021 when Evergrande, the country’s second-largest developer, warned it could not meet repayments after regulatory changes to debt limits. From July to September, foreign investors dumped more than $10 billion of shares in mainland companies through Stock Connect, the trading link between Hong Kong and exchanges in Shanghai and Shenzhen — the largest net selling since the program began in 2014. America’s big three institutional investors — BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street — own a minuscule percentage of the Chinese market, even as investment from China has poured into the U.S.

President Donald Trump highlighted the imbalance on a visit in 2017, decrying the “very unfair and one-sided” trade relationship. In response, the Chinese Foreign Ministry said it would lower entry barriers for outside investment in banking, insurance, and finance.

When it did, however, growth was hindered for unforeseen reasons. China ended ownership limits for foreigners in its financial sector in 2020, a year earlier than originally proposed, but the pandemic sharply curtailed outside investment activity for almost two years. At that time, most companies entering China set up as wholly foreign-owned enterprises under a 2016 law. Since restrictions ended, firms have been free to directly establish a mainland holding over which they exercise complete control or start a joint venture with a Chinese partner. Finance is the most popular sector for joint ventures between European and Chinese firms after consumer goods and services, according to Datenna, an open-source intelligence software company specializing in Chinese industry. In 2022, there were 159 fund managers in China, 58 of which were state-owned, according to data from the Asset Management Association of China. Of the 53 that were privately held, 45 were joint ventures established by foreign asset managers and their local partners. Just three were wholly foreign-owned enterprises: BlackRock, Neuberger Berman, and Fidelity International. Schroders joined them this year.

Authorities have been accelerating approvals for foreign managers to start their own mutual funds. BlackRock was the first to get the green light from the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) in 2021 to launch a wholly foreign-owned fund management company, enabling the firm to provide services to local investors. Then the CSRC went quiet until the end of last year, when a flood of approvals came. In November, Neuberger Berman became the second global firm to get approval, allowing it to start managing local currency funds. In December, Fidelity became the third. Fidelity already had a quota of $1.2 billion in funds as part of the qualified foreign institutional investor program, among the largest for any manager. It was also one of the first to register as a private fund manager with the Asset Management Association of China. Wholly foreign-owned enterprises are often seen as advantageous because they allow a company to keep all of the equity and control of the business, including internal operations and strategy.

Foreign firms identified this ability to bring fresh ideas to the Chinese market as a key edge.

“As the Chinese government continues to open up its financial market, we believe the China onshore retail fund and pension fund markets are ready for differentiated investment solutions from global investment managers,” David Guo, CEO for China at Schroders, said in January, when the firm won CSRC approval to start a wholly foreign-owned enterprise.

“The vast majority of foreign companies that set up have genuinely struggled, to the point to which many are now assessing [whether] they are viable,” Z-Ben’s Alexander says. “They have run out of money, and they are asking whether or not they should remain. It’s accurate, in working with some of these organizations, to say that the platforms and the strategies set forth in the beginning five or six years ago — these strategies were doomed to fail.”

Foreign firms face a number of challenges entering the Chinese market, not least around ESG. China is one of the few large economies not to align with the Paris Agreement’s target of net zero emissions by 2050. In recent years, alarming reports have emerged about the treatment of Uyghur Muslims in alleged labor camps, and China’s feud with Taiwan remains a foreign policy risk. “As we move to an increasingly multipolar world, questions remain around whether we will have regional or political blocs aligned with each other that will be in opposition to Western investors,” says Arif Saad, head of client advice at Dutch wealth manager Van Lanschot Kempen. “Grappling with these issues will be a key consideration when investing in China for both Western banks and underlying investors.”

Then there are the risks tied to intellectual property. In a sample of the 500 most capitalized joint ventures, Datenna found that in almost 70 percent, the U.S. partner was the minority shareholder. Chinese law grants shareholders with more than two-thirds of shares almost complete control over the company. When this type of arrangement is combined with a Chinese shareholder that also has strong government ties, the joint venture can fall under high risk of state influence.

Invesco and HSBC both have passive vehicles in which they own a chunk of the business and get dividends but allow a Chinese partner with links to the government to run the funds. Invesco’s 49-percent-owned joint venture, Invesco Great Wall Fund Management Co., raised $5.4 billion from Chinese investors in the first six months of 2022. The venture posted a profit of 756 million yuan. Invesco plans to increase its holding but is in no rush to buy out partner China Great Wall Securities Co., Andrew Lo, the Hong Kong-based CEO of the Asia Pacific unit of Invesco, told Reuters last September. The largest shareholder of China Great Wall Securities is Huaneng Capital Services Co., whose ultimate beneficial owner, China Huaneng Group, is wholly owned by the assets commission of the country’s State Council. Invesco says it went with a strategic partner rather than a financial partner to give it independence in distribution.

Similarly, HSBC chose the Chinese shareholder of HSBC Jintrust Fund Management Co., a joint venture running since 2005, for strategic reasons. The HSBC joint venture is with Shanxi Trust, which is 91 percent held by Shanxi Financial Investment Holding Group, an enterprise fully owned by the Department of Finance of Shanxi Province.

“State-owned enterprises’ decision-making process may not be as efficient as with a private company,” Matthew Levy, a partner at Faegre Drinker Biddle & Reath LLP in Indianapolis, wrote in a blog post. Chinese law requires special approval processes for investments or transfers of state-owned assets, he noted. State-owned enterprises may require internal approvals plus the okay from an asset management authority. Levy also highlighted the risks of tech transfer: “Technology should be segmented and distinguished so that the complete core technology is not exposed to the JV or the Chinese partner.”

Mutual funds may find looser rules around transparency and due diligence. “There has to be recognition that rules are different whereby you do not get the same level of transparency as you typically would in Western countries, nor does due diligence exist to the same degree,” Saad from Van Lanschot Kempen says. “Going forward, investors will have to assess what they are comfortable with and explain to clients why the upside of the investment opportunity remains such a positive one in spite of these known factors.”

But joint ventures also come with advantages, especially in attracting market share from established local firms. There are 120 local asset managers running public fund businesses in China, most with a range of products as well as track records and brand awareness from more than two decades of operation, according to Morningstar. Local funds also have established distribution networks.

Invesco has operated its China business with full regional authority, Z-Ben’s Alexander says, allowing the firm to compete better than most other foreign groups. HSBC and most other joint ventures require Chinese teams to strictly follow global operating practices, with zero room to adapt to local practices, he adds. “You have large global asset managers set up and management says, ‘Here’s our global operating manual; you need to follow it to the letter.’ This approach is a recipe for failure and is, today, a very significant issue.” HSBC said that from the outset, both partners in HSBC Jintrust Fund Management agreed that the joint venture would be operated to international standards while complying with local regulations.

“China has arguably the most open architecture in distribution anywhere in the world,” Alexander says. “That’s not your problem. Your problem is: How do you stand out? You need to have something to market.” He points to Fidelity, which has started fundraising for its first China product that will rely on Ant and Eastmoney Tiantian mobile portals to target investors. That marketing-centric drive is a first for a foreign manager in China, he says. Fidelity has put up the cash for prime placement on mobile apps of the two major portals, vying for eyeballs in a bustling marketplace. “Time will tell if the price paid is a line-item expense or an actual investment,” he noted on LinkedIn.

From this perspective, Vanguard’s partnership with Ant — in which Vanguard provided investment advisory services rather than asset management services — seemed like nirvana: the expertise of a Western powerhouse combined with the local knowledge of a Chinese distribution partner. But it wasn’t plain sailing. Because of Covid, Vanguard personnel couldn’t make it to China to work directly with Ant. It didn’t help that Ant entered the regulatory crosshairs. In 2020, after controlling shareholder Jack Ma infuriated government leaders by criticizing regulation for holding back technological development, President Xi Jinping personally decided to halt Ant’s IPO. The intervention was viewed as the culmination of long-running plans to rein in Ant. The news about the closure of the joint venture came two years after Vanguard announced it was abandoning plans for a mutual fund management license in China to focus on the Ant partnership.

The dust is yet to settle on Vanguard’s decision to exit China. But for rival firms struggling to produce revenues, a failure of that size could prove politically useful. It could also be a coping mechanism for companies unwilling to face defeat in a market and a culture unlike anything else they’ve seen. “China has made it clear they have their own rules of engagement — you’re not going to change them,” Alexander says. “You have to accept what they are and find ways to adapt your business — or decide not to and forgo the opportunity.”