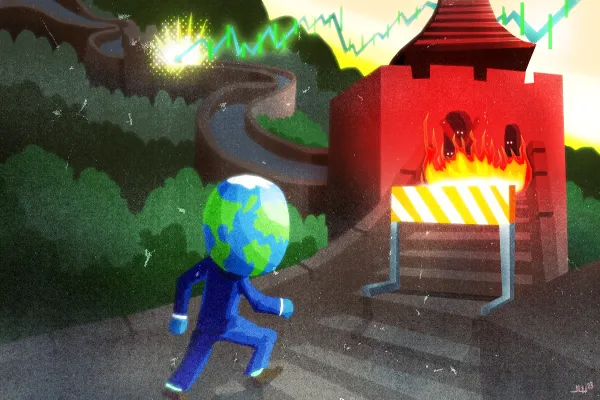

The recent disappearance of the executive chairman of Guotai Junan International Holdings is sending a chill across Hong Kong’s financial district, fueling worries that President Xi Jinping’s crackdown on alleged abuses in the securities industry is turning into a campaign against political rivals.

Yim Fung, a senior executive who oversaw the Hong Kong–based offshore arm of state-owned Guotai Junan Securities Co. for more than 15 years, has not been seen or heard from since November 18, according to a statement from his office. Executives are not sure of his whereabouts, but according to a November 24 report from China’s official Xinhua News Agency, government investigators have been probing the Shanghai headquarters of both Guotai Junan and Haitong Securities, two of China’s leading brokerage houses. Industry insiders say the chances are high that Yim is being held for questioning on the mainland as part of the financial industry probes.

Chinese authorities began cracking down on so-called malicious short selling and insider trading following this summer’s brutal stock market correction, which saw the mainland market plunge an unprecedented 40 percent between early June and late August and prompted Beijing to spend close to $300 billion to shore up prices.

In August investigators from the Communist Party’s Central Commission for Discipline Inspection detained several senior executives of Beijing-based CITIC Securities Co., China’s largest brokerage house. Overall, investigators have detained more than a dozen bankers — and even several senior officials of the China Securities Regulatory Commission — since launching the crackdown.

“When the market began to crash, there was a reflexive reaction to go after those were who responsible for it,” says Victor Shih, an associate professor of political economy at the University of California, San Diego, and an expert on China’s financial industry. “In reality, lax regulation and political pressure from the top were the main culprits. I am sure some people used this crackdown to settle political or even personal scores. The problem is that people will start to accuse each other, which can unsettle the market for quite some time.”

Although stock prices have recovered somewhat since August, the apparent widening of the financial industry investigations rattled the market last week. The Shanghai Composite index sank 5.5 percent on November 27, with a gauge of volatility surging from the lowest level since March. The Hang Seng China Enterprises index slid 2.5 percent on Friday in Hong Kong, whereas the Hang Seng index retreated 1.9 percent. The markets recovered slightly early this week.

On November 20 regulators reopened the market for initial public offerings, which had been suspended in early July to help steady stock prices.

Based in Hong Kong, Yim had a high profile in the local securities industry. He often spoke to the media as chairman of the Chinese Securities Association of Hong Kong. He also was a former aide to Yao Gang, a vice chairman of the China Securities Regulatory Commission who, until his arrest on November 13 as part of the industry crackdown, oversaw initial public offerings. Before joining the regulatory agency more than a decade ago, Yao had served in various roles as an investment banker in Shanghai, including as chief executive officer of Guotai Junan Securities from 1999 to 2002.

Yim was taken by Chinese authorities for investigation in connection with Yao’s case, Chinese Internet portal Sohu.com reported, citing an unidentified individual in Hong Kong’s financial industry.

With $196 million in investment banking revenues this year as of November 11, Guotai Junan ranked third among China’s brokers, according to research firm Dealogic, behind CITIC Securities and China Securities Co.

The financial crackdown is part of the larger campaign by President Xi to root out corruption, says Andrew Collier, managing director and founder of Orient Capital Research, a Hong Kong–based independent research firm. “Certainly, it has been widely accepted that new IPO listings and other share dealings often lead to big monetary gains for insiders,” Collier says.

But Yim’s presumed arrest, if confirmed, would carry political overtones too, Collier contends. Guotai Junan’s top executives were known to be close to aides of former president Jiang Zemin, whose power base is in Shanghai and who once served as the city’s party chief. According to several sources close to the party, Xi may be using the anticorruption campaign to challenge rival power centers, chief among them to the so-called Shanghai faction that Jiang heads. The disappearance of Yim and Yao’s arrest “look like an anti–Shanghai faction move,” says Collier, who served as president of the Bank of China’s operations in the U.S. from 2009 to 2011. “The Guotai arrests were shocking, as they seemed so clearly Shanghai-related.”

The arrest of top bankers from CITIC Securities — including president Cheng Boming, operations management head Yu Xinli and Wang Jinling, the vice director of information technology — may be an indirect attack on CITIC Securities’ chairman, Wang Dongming, who remains highly influential at the brokerage house, sources say. As the son of Wang Bingnan, a senior aide to former premier Zhou Enlai, Wang is known as a “princeling,” or son of a past party leader.

“Political logic here may be to discipline the princelings to some extent,” Shih says. “Perhaps the princelings had come to believe that they were above the law.”

President Xi himself is a princeling. His father, Xi Zhongxun, was a former aide to paramount leader Deng Xiaoping and was instrumental in the launch of the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone, a pivotal early reform initiative in the early 1980s. Analysts say, however, that Xi has been increasingly using his anticorruption campaign to silence would-be rivals within the party.

Regardless of the motives, there is no question that Beijing’s aggressive intervention in the market following the sharp correction and the subsequent arrests are causing concerns among investors. “The massive state intervention in the stock market in the wake of the crash was a serious setback for reform,” Shih says. “It will take years to repair. Restarting IPOs by itself cannot earn the trust of investors who are wondering when the government will issue another order forbidding share sales. Instead, credible institutional mechanisms need to be put in place.”

Follow Allen Cheng on Twitter at @acheng87.