Bob Iaccino for CME Group

AT A GLANCE

- July 2022 CPI fell on a YoY basis from 9.1% to 8.5% and was the first since May 2020 that didn’t show a month-over-month increase

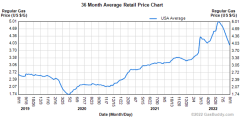

- Gas prices at the pump fell more than 20% between mid-June and mid-August, but are still 81% higher than two years ago

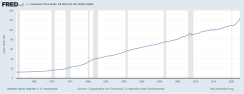

The July read of the CPI fell on a year-over-year basis from 9.1% to 8.5% and, more importantly, was flat on a month-over-month basis. The July read is the first that did not show a month-over-month increase since the May 2020 report, when we had a decrease of 0.1%. This monthly drop in the CPI was the last negative reading in a streak of three that occurred from March 2020 through May 2020, driven by pandemic-driven demand destruction. According to the St. Louis Federal Reserve's "FRED" website, in the week ending April 4, 2020, over 6.1 million U.S. workers filed for their first week of unemployment benefits, representing the highest number of initial claims in history.

Before that, to find even two consecutive months of negative month-over-month CPI growth, you have to go back to August and September of 2015.

People either forget or don't realize that the Consumer Price Index is precisely that – an index. When the U.S. Fed refers to its price stability mandate, they define it as an average of 2% growth in inflation on a year-over-year basis. When the CPI data is released every month, we see the rate of change in the index, which is almost always positive. Simply put, prices for the basket of goods represented by the CPI are almost always rising.

Many commodities, such as crude oil, corn, wheat and copper, have dropped in price recently. Gasoline prices have fallen substantially at the pump, a total of 20.45% since June 14 through Aug. 11. Prices were still 25.27% higher than a year ago yesterday and approximately 81% higher than they were in early August 2020.

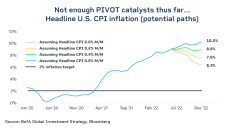

Prices of consumer goods rose so fast that, according to research done by Bank of America, even if we had 0.0% month-over-month inflation growth through the end of the year, the year-over-year rate of change in CPI would still be greater than 6.3%.

Friends and family ask me daily when prices will start going down. The complex answer is that some prices are going down right now, but the more accurate answer is they're not going back down to past levels for the foreseeable future, and maybe never on some products like autos and healthcare or healthcare insurance.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, prices for new cars are 9.01% higher in 2022 versus 2021 (a $3,151.75 difference in value on a vehicle that was $35,000 in 2021). In other words, for an equivalent purchase, cars costing $35,000 in 2021 would cost $38,151.75 in 2022. Compare that to a rise of only 4.47% from 2009 to 2019!

Even if car inflation slowed to 0.5% from the current 9.01%, a significant and unlikely drop, that $35,000 car would now cost $38,170.83. Reports would say that price inflation on autos has slowed from over 9% to just 0.5%, and that would indeed be a victory, but you may never see that same new car priced at $35,000 again.

A peak in the year-over-year and month-over-month rate of change in the CPI may be here, but "peak inflation" is not, as that phrase implies falling prices. What will help consumers if CPI rarely decreases? An increase in "real earnings." The definition of real earnings is an individual's income after considering the impact of inflation.

According to the BLS, "from July 2021 to July 2022, real average hourly earnings decreased 2.7%, seasonally adjusted. The change in real average hourly earnings, combined with a decrease of 0.9% in the average workweek, resulted in a 3.5% decrease in real average weekly earnings over this period."

Unfortunately, this negative trend in real earnings may reverse slowly, especially if the FOMC continues on the path of tightening monetary policy. Considering that peak inflation is not here and continues to run well above the Fed's intended target of 2%, more Fed tightening seems a likely outcome.

Read more articles like this at OpenMarkets