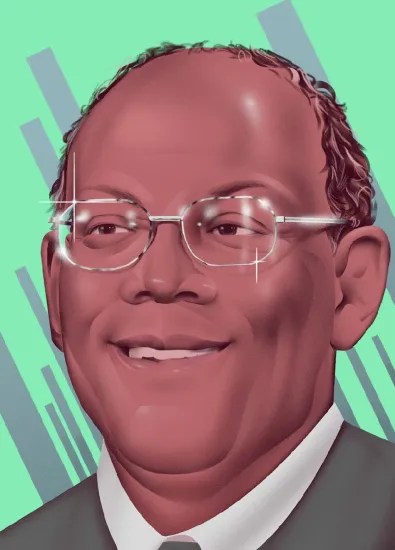

John Rogers Is Winning

Illustration by Richard A. Chance

The Ariel Investments co-CEO has triumphed in the boardroom and on the basketball court. Now he says value investing’s comeback is just beginning.

John Rogers

Chicago

Pete Carril

Ariel Investments

Michael Jordan