Illustration by II

By Mark Kramer, Nina Jais, Erin Sullivan, Carina Wendel, Kerry Rodriguez, Carlo Papa, Carlo Napoli, and Filippo Forti

Corporate leaders, investors, and analysts today must deal with two separate and entirely disconnected reporting systems: one for financial results and the other for environmental and social impact, or ESG, performance. Companies can be screened in or out using various criteria, but there is no way to integrate the data into earnings projections or valuation analysis. The result is two separate narratives, one telling how profitable a company is, the other highlighting whether it is good for people and the planet. There is no clear way to discern which company is most profitably doing the most good.

Investors, therefore, cannot accurately assess whether a company’s sustainability or shared-value strategies are creating shareholder value, and thus miss an important dimension of corporate performance that may affect future earnings. Eventually, an increase in shareholder value will manifest in long-term financial performance. But investors end up mispricing securities in the near term and management teams lose out on timely rewards in their market capitalization when those teams create shared value. This produces a strong disincentive for both investors and corporate leaders to prioritize social or environmental impact in their day-to-day decision-making.

Moreover, even if company executives want to give weight to societal priorities, the absence of any internal decision-making framework that integrates social and environmental impact with its economic consequences prevents them from finding optimal solutions.

No definitive evidence linked social and financial metrics until very recently. In the past few years, however, a growing body of research has demonstrated that there is a strong correlation between ESG performance on factors material to a given industry and the financial performance of companies over time, including stock performance. This suggests the possibility of a single hybrid measurement system that combines social and environmental impact with standard measures of financial performance to make the connection explicit.

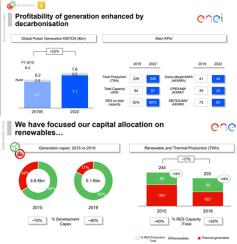

Italian electricity company Enel, for example, has a multiyear strategy to shift from fossil fuels to renewable power generation. This change, together with network digitalization, will offer higher profitability and lower volatility. Decarbonization, therefore, links directly to EBITDA. Once the correlation is validated, a hybrid metric based on the ratio of EBITDA to carbon intensity could be compared against industry peers’ to determine which utility is most profitably shifting to renewable energy.

That metric could also help predict changes in earnings based on planned investments in renewables or in decommissioning coal- and gas-fired power plants. Similar hybrid metrics could link profitability to health outcomes for health insurance companies or to nutritional value for food and beverage companies. They could also link employee productivity to wages and benefits in service and retail industries, or the cost of goods sold to labor conditions in the supply chain for clothing companies.

These connections will be meaningful only in cases where there are clear causal relationships between a change in social/environmental performance and financial results. In those cases it should be possible to create a few potent, comparable, and externally verifiable hybrid metrics in every industry, enabling investors, analysts, and corporate managers to factor a limited number of material social and environmental impacts directly into conventional financial analyses. Hybrid metrics could help fill out the emerging architecture of social and environmental impact reporting, increasing the accuracy of earnings forecasts and rewarding companies that perform best in both social and financial dimensions — with higher P/E ratios than companies that perform well in only a single dimension.

Linking social/environmental performance to standard measures of financial performance would be especially useful in an investment world increasingly driven by quantitative algorithms that cannot easily accommodate qualitative data. Hybrid metrics could also underpin a better internal decision-making framework, enabling managers to make choices that optimize both social and financial outcomes.

Bringing financial and ESG performance together would require significant changes in the ways that companies, investors, and analysts operate. For companies it would mean close collaboration among strategy, finance, investor relations, and sustainability officers, something that rarely happens today except in the few companies that have fully integrated sustainability into every aspect of strategy and operations. Among analysts and investors it would need an integration of key ESG metrics into security analysis, not as a final “green screen” that merely eliminates poor performers, but as an active element of company valuations and earnings projections. This would require broader expertise in social and environmental issues than is now typical among analysts and investors.

Each industry and, at least initially, each company may need to develop its own highly transparent metrics. It will take some time for them to become accepted, standardized by industry, and comparable across companies. Much more careful research will be needed to develop and validate the kinds of hybrid metrics we propose, but we have already seen indications that more clearly communicating the economic value of social and environmental performance can influence analyst and investor perceptions and raise company valuations.

Where ESG Ratings Fall Short

Understanding the potential of hybrid metrics first requires knowing why they don’t yet exist. After all, ESG and financial reporting developed in very different ways, each well designed to serve its intended purpose but never to be integrated with the other. Financial reporting has evolved over one hundred years to enable company managers and investors to assess the profitability of an enterprise. It is a highly detailed, externally verifiable, and thoroughly consistent system. Nowhere are social and environmental impacts captured.

ESG reporting is much younger. It was meant to hold companies accountable for the impact of their activities on people and the planet without regard to financial performance or profitability. The Global Reporting Initiative is the dominant standardized reporting framework within different industries. Some measures, such as carbon emissions, are consistent and externally verifiable, but many others, especially in the social dimension, are not. The GRI aims to be comprehensive, including nearly all social and environmental impacts, although many of them are not material to a company’s economic performance. The system makes no attempt to capture causal relationships between social/environmental performance and economic results. Further, the GRI provides no opportunity for companies to report on the positive impacts of creating shared value. For example, Brazilian pulp and paper company Suzano can report reductions in its carbon emissions from manufacturing. But nowhere in the GRI framework can it account for the positive effect of carbon sequestration from its many acres of fast-growing eucalyptus trees, which distinguish it from competitors that rely on less carbon-absorbent mature forests.

In addition to GRI reporting, investors often give weight to various ESG ratings and indices that attempt to list the most socially responsible and sustainable companies. But one assessor’s A+ is often another’s C–. Saudi Aramco — responsible for massive carbon emissions from the oil it sells — was rated higher than sustainability-focused retailer Costco by a top provider. A 2019 study found the correlation among leading ratings providers — including MSCI, Sustainalytics, Bloomberg, and RobecoSAM — to be only 30 percent. This contrasts sharply with a 99 percent correlation among credit ratings agencies.

An even greater variance is found among the world’s 125 different sustainability data providers. Even when the underlying GRI data is accurate, as it usually is (absent intentional fraud, such as in the Volkswagen emissions scandal), the individual ratings agencies each have their own definitions of socially desirable behavior and therefore weight the data differently.

Most investment firms that consider ESG factors rely on these ratings as the best data available, even as they acknowledge the flaws. Unable to directly connect ESG data with economic performance, investors use the ratings not as a meaningful predictor of corporate performance, but as a very blunt instrument that serves as a general proxy for risk and a final step in their selection process to eliminate poorly rated companies.

A Corporate Reporting Revolution

Until a few years ago, very few companies included social or environmental data in their reports to shareholders, instead sidelining that information in a sustainability report. A shift began with the Integrated Reporting Initiative, led by professor Robert Eccles, then at Harvard Business School. By 2017, 78 percent of the world’s largest 250 companies included some social or environmental indicators in their financial reports, almost double the 44 percent six years earlier, and 67 percent provided at least some external assurance of their data’s accuracy (although the majority of this assurance is limited to selective data). The European Union’s Non-Financial Reporting Directive will accelerate this trend for companies regulated by the EU.

The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board has gone a step further by working with companies to identify the most material social and environmental factors in each industry. SASB standards are increasingly being adopted by U.S.-based companies (although they were not developed to comply with the EU directive, a limitation that SASB is working to overcome). Recent research has demonstrated that the companies that focus their sustainability efforts on the material issues identified by SASB outperform their peers, delivering superior shareholder returns of 3 to 6 percent annually.

The few investment firms that conduct proprietary research to identify companies that derive material economic benefit from a distinctive approach to sustainability have substantially outperformed the market. But they remain outliers, and their deep company-specific research is not easily duplicated or translated into broadly applicable algorithms.

Many other efforts to connect sustainability with financial results are also underway. The Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures is developing methodologies for companies to detail climate-related financial risks. Ceres, similarly, has quantified the economic risk that carbon-dependent businesses face. The Impact Management Project is coordinating efforts to provide comprehensive impact investing standards. CEOs brought together by the World Economic Forum are advocating for standardized and comparable ESG metrics. And the Impact-Weighted Accounts Project, led by Harvard Business School’s George Serafeim, is working to create financial accounts that monetize different types of social and environmental impact. Despite all these worthy efforts, very few companies as yet describe any clear, consistent, and direct linkage between social/environmental and financial performance in their investor communications.

We do know, however, that social and environmental performance can influence financial results, especially for companies that pursue shared-value strategies. As Enel shifts a majority of its power generation to renewables, the company will see a faster return on capital investment, more-consistent earnings, a lower cost of capital from issuing SDG bonds, and a higher EBITDA margin. Walmart increased wages, training, and benefits for its hourly employees, and workforce productivity and same-store sales increased while turnover costs fell. Norwegian fertilizer company Yara has a distinctive competitive position and profit margins 17.5 percent higher than the industry average because its customized fertilizer mixes and technical support increase yields for small-hold farmers, justifying premium pricing, while reducing harmful runoff and deforestation. In Brazil, pulp maker Suzano’s business model speeds up its harvesting cycle and cuts costs. It also sequesters millions of tons of carbon from the air, which hardwood-pulp producers cannot match.

Why Hybrid Metrics Speak to Investors

We propose that the integration of social/environmental and financial reporting should go still further by using hybrid metrics that directly combine social/environmental and financial performance. A virtue of this approach is that it uses existing financial metrics that enable application of traditional tools of security analysis while also incorporating social and environmental factors. Before hybrid metrics can be adopted, they must be verified through quantitative analysis and by establishing a clear causal connection between social/environmental impact and financial results. Mere correlation may be misleading without an understanding of the underlying cause and effect.

Enel has long described its shift to renewables in its sustainability reports and taken pride in its efforts to advance sustainable development goals, but only in the past year has management made this information a key part of the company’s Capital Markets Day presentation, by focusing on the theme “sustainability = value.” Investor communications in late 2019 and early 2020 clearly highlighted the specific financial values driven by the renewables business model, including revenue, profitability, and reduced risk. From the Capital Markets Day presentation in November 2019 to February 2020 (when the Covid-19 pandemic deflated the market), Enel’s share price increased almost 24 percent and the company reached its highest-ever market capitalization. Management attributes much of the improved stock valuation to this shift in communicating the economic implications of the company’s renewables strategy.

Hybrid metrics, once vetted, should also enable comparisons and the development of common standards across companies within an industry. For example, if the increase in earnings for every 1 percent decrease in carbon intensity were higher for a certain company than for a competitor, we could conclude that the former had achieved greater efficiency in its renewables business, a factor that would become increasingly important as the industry continued the shift to renewables. If the company were also decreasing carbon intensity more rapidly, the difference in earnings between the two companies would be expected to accelerate.

Consider, for example, a hypothetical hybrid metric of EBITDA/CO2 intensity for three energy companies. According to the data, if one were to select the utility that is most rapidly decarbonizing, that would be Engie, even though the company’s profits have actually declined. Iberdrola, which is the second fastest in decarbonization and received the strongest ratings according to many ESG scoring systems, also comes out significantly better when one considers decarbonization and profit together — validating the sustainability ratings, but importantly demonstrating that the environmental impact is matched by strong financial performance. Enel comes out in between, decarbonizing more slowly than Engie but more profitably. Of course, EBITDA is also affected by different lines of business as well as by operational efficiencies unrelated to power generation and one-time transactions such as acquisitions and divestitures. Ideally, one would identify the financial metric most closely linked to social/environmental impact — in this case that might be the gross margin on power generation — which should offer a more meaningful and causally related hybrid metric. (Further validating this — or any other — hybrid metric would require a much more extensive statistical analysis across an industry.)

Static hybrid metrics like these compare competitors’ financial benefits from sustainability measures already achieved. Hybrid metrics that rely on changes over time — the correlation between the rate of decreasing carbon intensity and changes in profitability, for example — could predict the impact of sustainability targets on future financial performance. The metric that is best suited will probably vary based on a company’s strategy and the ultimate goal of the investor communication, although a good hybrid metric should be valid and consistent across an industry. The significance of the social/environmental component may also change over time. Once the energy industry has shifted entirely to renewables, the EBITDA/CO2 hybrid metric becomes anachronistic.

Or take a hybrid metric combining food and beverage companies’ profitability with nutritional value. Across the industry, companies are reducing salt, fat, and sugar in their products, although doing so diminishes consumer appeal and can result in loss of market share. Companies such as Nestlé, however, have found new technologies that preserve the original taste using less of the unhealthy ingredients — for example, mixing ice cream at lower temperatures to preserve the mouth feel of higher fat content and coating ingredients so that salt remains on the food surface, where it is tasted rather than being absorbed and diluted. Presumably, investors would like to know which companies are moving to healthier ingredients while maintaining profitability and which are simply sacrificing profits for nutrition.

Multiplying a company’s EBITDA margin by the index score from the Global Access to Nutrition Index yields a distinctly different result than profitability or nutrition alone. As consumer tastes and government regulation increase pressure for healthy food and beverage offerings, it will be increasingly important to understand not just which companies are profitable and which offer good nutrition, but which companies offer good nutrition most profitably.

Instead of considering profit and the nutritional profile equally, some investors may wish to give greater weight to profitability, others to social impact.

Hybrid metrics may also be valid only within certain limits. For example, the correlation that Walmart found between raising hourly compensation and increasing productivity makes sense at lower wage levels, but would probably not hold true if wages continued to increase indefinitely. A hybrid metric that links wages and productivity in retailing, therefore, would be valuable only within a specific range.

Hybrid metrics may show negative correlations as well as positive ones. For an automobile company, a hybrid metric that links profitability to the average gas mileage of cars sold might show that profitability is heavily dependent on sales of SUVs and trucks, which consume more fuel, even if the company’s GRI report shows it has reduced the carbon intensity of its manufacturing process. Such an assessment would much more explicitly illustrate the risk of carbon regulation for the company’s profitability than do current ESG ratings of the company’s overall carbon footprint. The table below lists a few other potential hybrid metrics that might apply in different industries. Considerably more research will be required to define and test the most meaningful hybrid metrics for each industry.

We do not suggest that hybrid metrics should replace GRI reporting or other ways of tracking corporate social and environmental impact. Narrowing the focus to a few key hybrid metrics for investment analysis will not excuse companies from responsibility for other aspects of their social and environmental footprint. Governments, nongovernmental organizations, and socially responsible investors will rightfully hold companies accountable for a wide range of social and environmental impacts, whether or not they are material to shareholder returns.

Hybrid metrics can also guide internal corporate strategy and decision-making by bringing societal and business outcomes into the same analytical framework. Discovery Limited, a health and life insurance company based in South Africa, has developed a distinctive business model that rewards its members for engaging in healthy behaviors, such as exercise, a good diet, and preventive care. The incentives have been shown to change behavior, leading to 15 percent lower medical costs and an eight-years-longer life expectancy, in turn increasing Discovery’s profit margin. Discovery has developed an equation that links the cost of incentives with the resulting changes in behavior and improvements in health outcomes, along with the cost savings to the company from reduced medical bills. This analysis helps guide management decisions about the viability of new incentives and product offerings.

The Obstacles — and How to Get Around Them

If hybrid metrics are to take hold, companies and investors will need to confront several normative factors in the capital markets system that currently impede the linkage of social/environmental and financial performance through various policies, practices, and deeply embedded mind-sets. For example, companies are often advised by legal counsel not to disclose any data unless they are legally required to do so. Only Intel and Clorox among S&P 500 companies voluntarily include sustainability data in the business or strategy sections of their 10-K filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission. Regulatory requirements to disclose social and environmental impact data are increasing, especially regarding climate change, but as yet only France and South Africa now mandate extensive disclosure.

Other concerns include the risk of litigation if a future prediction fails to materialize and the reluctance of outside auditors to provide assurance about social and environmental outcomes. These obstacles are reinforced by stubbornly persistent mental models of both the investment community and corporate leaders. Many investors still see consideration of social and environmental issues as irrelevant to security analysis or, in some cases, as an actual violation of fiduciary duty. And many executives continue to look at such issues as merely a matter of corporate reputation and a vague license to operate rather than as a driver of competitive advantage and bottom-line results. Both the investment and corporate communities will need to change their thinking if social/environmental and financial metrics are to be linked effectively.

First and foremost, company leaders must approach social and environmental issues from the perspective of shared value, intentionally building a social-value proposition into their competitive positioning as a source of differentiation. This can be done by developing new products and services that address social and environmental needs or reach underserved populations. For example, publicly traded DSM, originally the Dutch State coal mining company, exited coal decades ago and committed to selling only sustainable products by using the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals as an initial screen to prioritize product development. And Unilever uses highly innovative distribution systems to deliver hygiene products to rural villages in India. This kind of social-value shift can also be accomplished through improvements in productivity within a company’s or suppliers’ value chain. Walmart has added billions of dollars to its bottom line over the past decade through greater efficiency and renewable energy initiatives that have reduced its carbon footprint. Or change can be achieved by improving conditions in the communities where a company operates. Novo Nordisk has invested heavily, in partnership with universities and government agencies, in improving awareness and treatment of diabetes in China, resulting in a dominant market share for its medicines and a reduction in morbidity and mortality.

Communicating shared-value strategies requires a clear narrative about how a company’s positive social and environmental impact will deliver shareholder value over time. This means that a business must disclose longer-term strategies to investors and analysts, rather than focusing exclusively on near-term earnings. It must also measure and report its impact on the most material social and environmental factors in its investor and analyst communications, ideally with reference to the materiality analysis developed by SASB or the EU reporting directive. This requires zeroing in on the few material impacts that actually affect key financial metrics, such as revenue growth, profit margins, and return on capital, and making that connection explicit. Last, a company must develop highly transparent formulations of hybrid metrics, in collaboration with its auditors, to ensure that investors can understand and trust the data being presented. Of course, reporting must also include the necessary caveats and qualifications to safeguard the company in making forward-looking statements.

In its investor presentation in March 2020, Enel moved to aggressively highlight how sustainability is integrated into its business model and drives economic value, with clear quantitative data. Analysts and investors reacted very positively.

This kind of reporting is possible only when there is a company-wide understanding of the link between social/environmental and business strategies and sufficient collaboration among the sustainability, finance, and investor relations teams.

Yogurt concern Danone said in February 2020 that it would begin pricing carbon emissions into its quarterly earnings, reporting on carbon-adjusted earnings per share. The new measure is calculated based on the estimated cost per share of the tons of greenhouse gases the company generated in 2019, which is then subtracted from regular EPS. The calculation shows that carbon-adjusted earnings per share grew more quickly than regular EPS in 2019. Danone also announced significant investments in product improvements to address climate change, which are expected to “deliver in the midterm a consistent mid- to-high-single-digit recurring earnings per share growth.”

Companies such as Danone and Enel go well beyond SASB’s materiality analysis to clarify how their shared-value efforts differentiate them from competitors and confer meaningful competitive advantages. Of course, once companies begin to report on these metrics, they must continue to do so, making it clear to investors that these social and environmental strategies are core to ongoing corporate strategy and economics. The NYU Stern Center for Sustainable Business’s Sustainable Share Index, for example, compares sustainable consumer product performance with standard product performance, finding 5.6 times faster growth for the former.

As noted earlier, it is important to show a clear causal relationship between the two components of the hybrid metric, as well as the potential limits of its range. One can find correlations and construct ratios between all kinds of data points, but a metric will be meaningful only if the connection between social/environmental and financial variables is clearly understood. To pressure-test the connection between variables, companies can analyze whether the correlation holds true across multiple years of internal data, as well as in comparison to competitors.

Linking social and environmental impact to standard financial performance metrics seems far more reliable and informative than using newly invented metrics such as social return on investment, net benefit, and total return, which fail to convey economic significance to investors or fit into ordinary security analysis. Investors already struggle to determine what really matters from an endless sea of ESG data and ratings, as companies are saddled with ever-more-numerous social and environmental reporting obligations.

Hybrid metrics have the potential to reduce, rather than expand, the volume of relevant data for both companies and investors. They could also help investors make better-informed decisions and tighten the feedback loop for companies between positive impacts on the world and their own stock prices.

Stock (Out)Performance and Shared Value

The scarcity of companies that disclose the financial impact of their social/environmental efforts prevents any comprehensive analysis to confirm that stock performance and analyst predictions respond to the types of reporting recommended here. We did, however, compare 21 companies across seven industries, separating them into three categories within each industry: (1) “business as usual” companies that do not follow shared-value strategies, (2) “limited communication” companies that follow shared-value strategies but do not communicate the economic benefits, and (3) “strong communicators” that both follow and communicate the economic value of shared-value strategies.

We found that the shared-value companies in category 2 reported more frequent positive earnings surprises, surpassing earnings estimates 66 percent of the time, compared with 54 percent for their business-as-usual category 1 competitors. This finding is consistent with previous analysis and with our hypothesis that the financial and competitive advantages of shared-value companies are often underestimated.

We also found much less variation in analysts’ earnings estimates for category 3 strong communicators, with the average scaled forecast dispersion nearly three times higher among the limited communicators. Last, we discovered that the strong communicators benefited from P/E ratios that were on average 40 percent higher than industry norms. Despite these initial findings, it is important to acknowledge that many other factors affect earnings surprises, forecast dispersion, and P/E ratios, so our analysis affirms, but does not prove, our hypothesis.

The few investors that have been able to identify strong signals about successful shared-value strategies have consistently outperformed the market. In its first ten years, the average return for Generation Investment Management’s global equity fund was 12.1 percent a year, more than 500 basis points above the comparable MSCI index’s growth rate. Over the past seven years, the AB Sustainable Global Thematic Fund’s 10.46 percent annual return beat the MSCI All Country World Index by 4.47 percentage points, outperforming 93 percent of peers.

Actively managed funds and research analysts are best positioned to meaningfully interpret and act on hybrid metrics that convey shared-value strategies, but if our hypothesis is correct, sooner or later all types of investors and analysts will need to integrate a deeper understanding of social and environmental issues into financial analysis and industry expertise.

Doing the Work

Making this transition will require a number of changes on the investor and analyst side. For example, investors will need to integrate social and environmental factors into security analysis from the start, identifying shared-value opportunities through industry-by-industry analysis in light of social and environmental trends. Instead of relying on external ESG ratings, Pimco, for one, develops forward-looking ESG-driven sector frameworks by industry, built on company disclosures and proprietary trend analysis. For many analysts this will require them to incorporate longer-term trends in social and environmental factors, along with unconventional sources of data and new types of expertise.

Analysts must ask companies the hard questions about the link between shared value or ESG performance and economic results, and push for alignment of compensation with social impact as well as economic performance. In particular, investors must consider the “S” in ESG as equally important to the more easily quantified “E.” This is particularly true as companies become more aware of the significance of racial equity in all aspects of their operations. And to the extent that shared-value strategies span multiple years, a longer-term perspective and compensation structure will be important to shifting the investment industry.

We believe that investors can improve the accuracy of their earnings projections and that companies can improve their near-term market capitalization by better articulating to investors how their social and environmental strategies create value for shareholders. This requires first that companies approach material social and environmental issues as a source of differentiation and competitive advantage through strategies that create shared value. Second, companies must consistently communicate, through normal investor presentations and reports, how their shared-value efforts will affect future earnings and provide competitive advantages relative to others in their industry.

Last, we see an opportunity for companies to create hybrid metrics that directly combine improvements in social and environmental impact with changes in standard financial indicators, such as EBITDA, return on capital, and cost of goods sold, both for use as internal decision-making guides and for external reporting. Once appropriately devised and tested, hybrid metrics can more easily be integrated into security analysis and trading algorithms by investors, as well as into capital allocation decisions by companies, with greater significance, standardization, and verification than in prevailing ESG ratings.

This approach, along with the development of hybrid metrics, goes well beyond current best practices in ESG ratings, integrated reporting, and materiality assessments. The few leading companies that have already started to make these shifts in investor materials have seen positive responses. But these changes are very recent, and many innovative companies with social and environmental strategies that improve economic performance are still going unrecognized and unrewarded by investors.

Until we embrace a new set of metrics that bridges social/environmental and financial reporting, we will never fully understand these two interdependent dimensions of corporate performance.

Mark Kramer is a founder and managing director of social impact consulting firm FSG and a senior lecturer at Harvard Business School. FSG co-authors include director Nina Jais, associate directors Erin Sullivan and Carina Wendel, and consultant Kerry Rodriguez. Enel Foundation co-authors include managing director Carlo Papa and senior researchers Carlo Napoli and Filippo Forti. Thanks to George Serafeim for his guidance.

This article derives from the report “Hybrid Metrics: Connecting Shared Value to Shareholder Value,” published by the Shared Value Initiative. It is based on research funded by the Enel Foundation, with support from Francesca Gostinelli (head of group strategy, economics and scenario plan), Monica Girardi (head of investor relations), and Giulia Genuardi (head of sustainable planning & performance management) of the Enel Group.