At 3:00 in the afternoon on Thursday, November 14, a small group of the world’s most powerful people prepared to board two chartered airplanes in two separate European capitals.

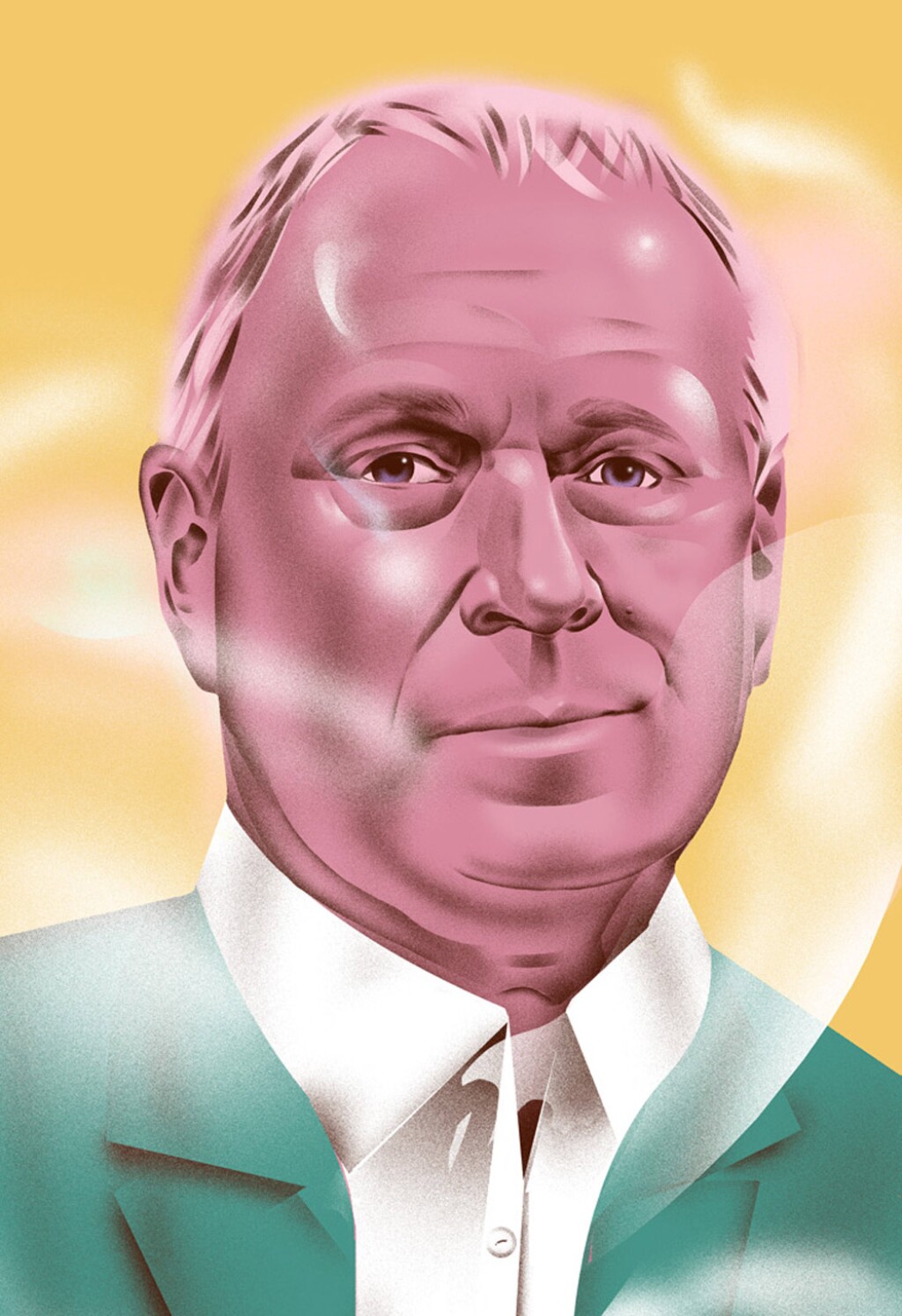

They were headed for Philadelphia for a weekend-long event that had been several years in the making for its creator, Nicolai Tangen, the Norwegian founder of one of Europe’s most successful hedge funds, London-based AKO Capital.

“You are all exceptional,” Tangen wrote in the program for the event. “You all want to extend your range and open your minds. But, like me, you may not always have sufficient time in your daily lives to do this, which is why I have had to whisk you away to learn not only from some of the world’s most inspiring speakers and professors, but also from each other.”

He called it the “dream seminar.” The 150 attendees included psychotherapist Esther Perel, former U.K. Conservative Party leader William Hague, celebrity chef Jamie Oliver, and some of the most powerful people in Norway, including the ambassador to the United Nations, government ministers, government lawyers — and Yngve Slyngstad, the chief executive of the Government Pension Fund Global, otherwise known as “the oil fund.”

Days before, Slyngstad had announced his decision to resign as chief executive of the oil fund — the largest sovereign wealth fund in the world — after an impressive 12 years, during which the fund had topped $1 trillion in assets and sparked headlines for announcing its intention to divest from shares in the very asset from which it derives its wealth: oil.

But even for a man of Slyngstad’s stature, a man who spends much of his life speaking at finance events, the dream seminar was notable for its opulence.

Passengers at London Stansted boarded the Crystal Skye, described as “the world’s newest . . . and most spacious luxury jet.” This adapted Boeing 777 contains a restaurant for 20 people, a chef, butlers, two wine bars, and spacious bathrooms, plus seats that can be made into fully reclining beds, furnished with 24-inch televisions. From Oslo, participants traveled in a large Airbus passenger plane, done up entirely as business class. The two flights alone cost Tangen $1.4 million.

Fredrik Sejersted, a government lawyer, described the journey to Norwegian tabloid Verdens Gang as “a luxurious crossing and most unusual for most of us.” Knut Brundtland, an art collector, says guests were invited to attend with all expenses paid — something he notes was “exceptionally generous.”

In Philadelphia, the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania — Tangen’s alma mater — collaborated on the program, in which leading academics, artists, celebrity chefs, and Olympic athletes gave talks on topics ranging from cancer to trust to art. The evenings were crammed with drink receptions, networking events, and nightcaps in the library of the Inn at the Penn hotel, with entertainment from Gregory Porter and Sara Bareilles. On the Saturday, during a day of activities titled “Ready for the Future?,” Slyngstad appeared on a panel called “What type of economic system do we need to prosper into the next decade and beyond?” with Wharton School dean Geoff Garrett and Marc Rowan, co-founder of Apollo Management. It was just half an hour long, before a sandwich lunch, and paled in the excitement of that evening’s entertainment: Sting, who played an hourlong concert that cost Tangen $1 million.

Participants were encouraged to keep quiet about the dream seminar. Tangen later claimed this was to solicit “good discussions and proper exchanges of opinions.” Perhaps because of this, the event went entirely unnoticed by the press anywhere in the world.

That is, until after March 26, when Norges Bank Investment Management — the authority charged by the Norwegian central bank with the day-to-day running of the oil fund — held a press conference via videolink from its offices in Oslo. The conference had been convened to announce Slyngstad’s successor as head of the oil fund from a short list of eight men, released a month earlier, including one anonymous applicant and two internal candidates. But the person who appeared on the screen was not on the short list, not even as the unnamed man.

It was Nicolai Tangen.

Norwegians are oddly affectionate toward their oil fund. It acts as a financial reserve, smoothing out revenue and hedging against fluctuations in the price of oil, but also as a national savings account. The fund provides 20 percent of the annual government budget, though a fiscal rule ensures Norway does not spend more than the real return of the fund, which is estimated to be about 3 percent per year. Today less than half of the value of the fund comes directly from oil and gas production; most is from returns on investments in equities, fixed-income, and real estate in international, rather than domestic, markets — hence the name: the Government Pension Fund Global.

At $1.1 trillion in assets, the oil fund is likely the largest sovereign wealth fund in the world, a quarter of a trillion dollars bigger than its nearest neighbor, the China Investment Corp. It wields considerable influence in global stock markets, owning 1.5 percent of all shares in the world’s 9,000 listed companies, alongside hundreds of buildings in global cities that provide rental income. It also has a steady flow of income from lending to countries and companies. In recent years, under the leadership of Slyngstad, the oil fund has shown increasing willingness to hold companies to account over social and environmental issues: It no longer invests in producers of coal or coal-based energy, nuclear weapons manufacturers, producers of tobacco products, and companies that have been shown to violate human rights. Since 2016 the oil fund has adopted many measures in the fight against tax havens and financial secrecy. As recently as March, NBIM’s chief corporate governance officer and the Norwegian central bank’s head of sustainability for corporate governance declared publicly that maximizing long-term value “does not require aggressive tax behavior” and that as an investor, NBIM expects multinational enterprises to exhibit tax behavior they consider “appropriate, prudent, and transparent.”

So it was with some surprise that Norwegians turned to look at the investing record of Nicolai Tangen, the shock successor to Slyngstad as chief executive of the oil fund.

Tangen has personal investments worth £67 million ($85 million) in funds and companies based in tax havens in 2020, according to VG, including 284,913,910 Norwegian kroner ($31 million) in “The Russian Property Fund” and $14.1 million in the “Ennismore European Smaller Corporation Companies Hedge Fund,” both registered in the Cayman Islands. He also has an ongoing case between his company, AKO Capital, and the British tax authorities relating to incentive schemes. Her Majesty’s Revenue & Customs, the authority that collects taxes in the U.K., declined to comment on or confirm the case, but Tangen himself told VG in April: “It is a so-called ‘deferred payment scheme’ that most in the industry set up after the financial crisis to create even better harmony between investors’ and managers’ interests.”

How do we know all of this? Because in the month that followed Tangen’s appointment, the Norwegian press went bananas.

They pored over Tangen’s personal investments, scrutinized the hiring process and why he didn’t appear on the short list of applicants before his appointment — experts even speculated that the omission was criminal — and excavated as many details as possible about the extravagant dream seminar.

Official after public official came forward with apologies for having attended the seminar without making the proper declarations to the public. “I should have been more open,” said Torbjørn Røe Isaksen, former minister of trade and industry in the government, about his decision to go. The ministry scrambled to pay back the cost of his hotel bill and meals, and there was hand-wringing about whether he should pay for the concert with Sting. The U.N. decided to cover the stay at the Penn and meals for Mona Juul, the Norwegian ambassador, after it was contacted by the press.

Slyngstad was the most heavily scrutinized. Norges Bank was forced to investigate his travel, revealing he had caught the train from New York to Philadelphia on Norges’s dime but had slept and eaten at the conference at Tangen’s expense, as well as taking the plane chartered by Tangen home from Philadelphia to Oslo out of “convenience.” Slyngstad also revealed to VG that he had attended the seminar in his professional capacity as head of the oil fund, and that he spoke about his resignation at the event, though not directly with Tangen. He did not, he said, personally encourage Tangen to apply for the job. But emails requested by Dagens Næringsliv, a Norwegian newspaper, on April 3 reveal that the two men had been in contact from August 2016 — and that that contact dwindled in 2020, when Slyngstad stopped responding to Tangen’s emails, messaging Tangen again only to congratulate him when his appointment was announced.

“I am really, really sorry,” Slyngstad wrote in a message to employees, admitting he had “really screwed up.” He added: “Since this will be my last business trip as head of the oil fund, I am embarrassed to have made such a mistake this time.”

The stories sparked a public debate in Norway about the place of gifts in public life. “If you want to apply for a construction permit in Norway, you would not bring a basket of fruit to the public official managing your case,” says Tina Søreide, research leader for the corruption and criminal law unit and professor of law and economics at the Norwegian School of Economics. “Those who work in the oil fund are not supposed to accept even a silk tie. But this seminar was so far beyond that, there was no recognition of the difference between the public and the private. It goes beyond Tangen to reveal a lack of consciousness about gifts.”

In the aftermath of these revelations, the 15 members of the Norges Bank Supervisory Council, which oversees compliance at the central bank, has repeatedly written to the central bank for more details about Tangen’s appointment. On April 23 the council sent 26 questions detailing problematic aspects of the appointment and demanding a full written account. A week later, Norges Bank responded with an 83-page document. It contains details of Tangen’s personal investments and those of AKO Capital, which manages $20 billion across long-only and long-short equity funds; the AKO Trust, established in 2002; and the AKO Foundation, a charitable foundation. (Tangen declined to be interviewed for this article.) A spokesman for Norges Bank tells Institutional Investor rather optimistically that Tangen had “decided to stay under the radar media-wise” until he starts his new job in September. But in April, VG asked him what he thought about having invested heavily in tax havens like the Cayman Islands and Jersey, given he was about to take the top job at a fund that has been striving for tax transparency and cracking down on the use of tax havens.

His answer? Everyone’s doing it. “This is a Cayman-registered fund in line with approximately 60 percent of this type of fund in Europe,” he said.

Then, in a development that left many Norwegians reeling, Norges Bank backed him up. In a letter, Øystein Olsen, governor of Norges Bank, wrote that all of Tangen’s tax arrangements were legitimate — because Jersey and the Cayman Islands, though they are frequently referred to as tax havens, are both members of the OECD Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange for tax purposes. That forum scores countries on one measure, and by this measure — willingness to exchange information — the Cayman Islands scores similarly to Denmark and Germany.

The tax havens, according to Olsen, aren’t actually all that bad, if you evaluate them by the single fact that they have agreed to share some data. But under the 20 criteria of the Financial Secrecy Index — which ranks a country based on how well its legal and financial system allows wealthy individuals and criminals to hide and launder money — the Cayman Islands is the biggest enabler of financial secrecy in the world in 2020. “So they are saluting the tax havens,” says Sigrid Jacobsen, director of Tax Justice Network Norway. “What we consider to be the worst of the worst has been saluted by the head bureaucrats of Norway. They are spinning words.”

In the months since, Tangen has worked with Norges Bank to separate himself from his personal financial interests and those of AKO Capital. He will move to Norway and pay taxes in Norway, where his salary, as chief executive of the fund, will be just $630,000. For the duration of his time at the oil fund, all dividends arising from his stake in AKO, already diminished from 78 to 43 percent, will be donated to the AKO Foundation. He has closed the AKO Trust. His wealth has been placed in a blind trust with Norwegian fund manager Gabler investments. Tangen has also stepped down from all AKO boards. In accepting the changes, he said, “Trust is something you don’t take, you get.” Norges Bank wants to draw a line under the affair. On May 28 it announced that Tangen’s employment contract had been signed. “With Nicolai Tangen we will have a highly skilled leader of the Government Pension Fund Global,” Olsen said, announcing, for the second time, the appointment. “Tangen is a man with good leadership skills and unique experience from international capital markets.” Tangen is due to start the job on September 1.

But for many Norwegians the debate is not yet over.

“The oil fund belongs to the Norwegian people,” wrote Anja Bakken Riise, leader of Future in Our Hands, Norway’s largest environmental organization, in a June op-ed in VG. The democratic roots and the ethical profile of the fund are at stake, she claimed, concluding, “The Parliament should take back control and stop Norges Bank’s employment of Tangen.”

Jacobsen goes one step further. She says Olsen stood behind Tangen and pushed for him to sign his employment contract even though there were still many questions left to answer.

“When the appointment was finalized and signed, Olsen said he had the whole board of the central bank behind him and that the committee can’t affect this hiring process,” she notes.

Then Jacobsen made an even more astonishing point. If the committee decides unanimously that there were irregularities in the hiring process, or that conflicts of interest remain, it’s not just Tangen’s position that would be compromised, she says. The whole board of the central bank could have to stand down.

Many Norwegians see three irregularities. There are the numerous personal global financial interests, including Tangen’s attachment to tax havens. There’s the way the media chaos since March has been handled by Norges Bank. But the looming question that occupies many minds is: How did Tangen, not even short-listed by the bank in March, come to take the job?

He was not a well-known public figure in Norway before 2020. Tangen was born in Kristiansand, in the southernmost part of Norway, and trained in interrogation and translation in the Norwegian Intelligence Service. He studied at the Norwegian School of Economics and then the Wharton School as an undergraduate in the class of 1992.

He’s a scholar, with two master’s degrees — one in art history from the Courtauld Institute of Art in London and another in social psychology from the London School of Economics. But Tangen also has a formidable reputation in his chosen career of finance. After stints at Cazenove & Co. and Egerton Capital, he started his own hedge fund, AKO Capital, in 2005 in London. He has made London his home for three decades, overseeing AKO Capital as it has grown to $17 billion under management and 70 employees. In recent years, Tangen has been a regular face on The Sunday Times’ Rich List, a popular ranking of the U.K.’s rich and famous, where he was listed as one of the U.K.’s most successful hedge fund managers in 2018 and ranked 251st-richest in the U.K. in 2020, with an estimated net worth of £550 million.

As his net worth has grown, Tangen has followed the lead of Richard Branson and Bill Gates, men who make heavy use of favorable tax arrangements and then win headlines for promising to give their wealth away. Tangen took the Giving Pledge — the Gates initiative in which the wealthy promise to give half of what they have to philanthropic causes during their lifetimes or in their wills — with his wife, Katja, in 2019. In 2013 he established the AKO Foundation, which has a focus on education and the arts. One of its biggest donations to date is a $25 million gift to the University of Pennsylvania, where he has been honored with a “transformative new campus building to be named Tangen Hall,” plus an international scholarship fund.

Norwegian experts have described Tangen’s giving as “personal brand building.” Peggy Brønn, professor emeritus at the Institute for Communication and Culture at Norwegian business school BI, tells VG, “It looks like he puts himself in a position close to those who have influence and that he himself will also have influence. There is nothing wrong with that, but it is important that it appears genuine.”

As with the dream seminar, Tangen’s actions have sometimes misfired. Tangen seemed unprepared for the backlash that surrounded his appointment, telling the Financial Times in May that the previous few weeks had been like being in the “middle of a tumble dryer.” In Norway he is best known in his birthplace, and more widely for his expansive collection of Nordic art — sometimes touted as the largest in the world, with more than 3,000 works. Through the AKO Foundation, Tangen is converting a grain silo in Kristiansand into a museum to display his art, with an opening date of 2021. The project has caused upset over costs of more than NKr600 million, split among local taxpayers, the state, and Tangen. “I thought I was doing something nice,” he tells Norwegian Broadcasting (NRK). “I never thought it would cause so much uproar.”

These missteps ring alarm bells among onlookers. Some fear that Norway — a small country with a population of just 5 million, where the elite naturally move in very small circles — will face further reputational damage beyond the bungled processes that led to Tangen’s hire.

“Norway has a self-image of being a meritocratic society, but that’s not entirely true,” says Sony Kapoor, managing director of international think tank Re-Define. “It suffers from having small networks of people who grew up together, went to the same university, and it is often this network that runs the country.” Kapoor says that professionals tend to rotate around the Finance Ministry, the central bank, and the statistics bureau — which he describes as the “golden triangle.” In 2018, Norway fell from third to seventh place in a global ranking of corruption perception, suggesting the Norwegian people’s confidence in the government had fallen.

At the August parliamentary committee hearing, ministers will take another look at the processes that allowed Tangen to get the job. They will note that his name appeared on a long list of 41 potential candidates assembled by recruiter Russell Reynolds Associates at the start of 2020, but then disappeared from the list in the months before he was announced as the winning candidate. Although the parliamentary hearing cannot legally reverse Tangen’s appointment, it could make his position untenable if it emerges that rules were broken — and could jeopardize the legitimacy of Øystein Olsen, the governor of Norges Bank and chair of the bank’s board. Ministers will have to decide if Norges can move past the scandal, even as ordinary Norwegians continue to speak out in disgust.

Bakken Riise says that it “just doesn’t feel right” that Tangen should become head of the oil fund at a moment when it is stepping up pressure on companies and governments to become more responsible for social issues and the environment. “Today the fund has had a role as this sustainability lighthouse,” she says. The oil fund uses “expectation documents” setting out criteria that all the companies in which it invests must meet on tax, transparency, corruption, climate change, and human rights. “It is always pushing what you can expect from an institutional investor. When you have this man at the top who doesn’t have credibility when it comes to some of these issues, can we still expect the companies to take such care?”

But a bigger risk — aside from reputation — is that the scandal clips Tangen’s wings at a moment of considerable market volatility, when Norges might otherwise have leaned on its new head’s expertise. Although the oil fund rode out the 2008 financial crisis relatively unscathed, coronavirus and a sharp fall in oil prices created the fund’s worst quarter on record, with a 16 percent drop in the three months to April. At the same time, the Norwegian government has been battling rising unemployment, which had quadrupled by the end of March. The government may have to draw down record amounts from the fund at the same time that its revenues slide.

Tangen is a celebrated stock picker. But the oil fund is de facto an index tracker fund, which is forbidden from investing outside of listed stocks and bonds, except in unlisted property. NBIM, whose investment management arm Tangen will soon lead, must keep to benchmarks set by the Finance Ministry, with a tracking error of just 1.25 percent. “The role of chief executive is not very influential on the way the fund is managed,” says Kapoor. He points out that though NBIM has a staff of more than 500 well-qualified and experienced managers, it is fewer than 20 bureaucrats in the Finance Ministry, “with little financial expertise and no experience,” who really call the shots. “The job is high-profile, yes, but the difference between a good job running NBIM and a bad job running NBIM is not really noticeable in terms of performance, because it only has a [small] tracking error from the benchmark set by the Finance Ministry. Room for maneuver is very limited.”

This was a problem encountered by Slyngstad during his 12 years as head of the fund. He called repeatedly for the fund to enter into new asset classes such as private equity — calls that were rebuffed by the Norwegian government and the central bank. In 2018, a year before his departure, Slyngstad presided over a momentous inquiry into whether the oil fund should continue to be housed in the central bank, itself a highly unusual arrangement unlike those of other large sovereign wealth funds. In China and Saudi Arabia, for example, there is a division between central bank reserve funds and sovereign wealth funds. Inside Norway’s central bank, the oil fund plays a major role in public markets. Outside, an expert committee proposed, it could have a much greater role in infrastructure and property, plus other less liquid and private assets — assets that Norges Bank might not have the competence to effectively oversee from the inside. “This decision is the most important for the last 20 years for the fund,” Slyngstad said in October 2018, admitting that the issue, more than any other, was keeping him up at night.

Now Slyngstad is gone and the Norwegian government has resolved to keep the fund where it is. The scandal over his appointment has shielded Tangen from questions about his intentions for the oil fund, including whether he will push for more active management — a strategy that would be natural given his experience. Tangen has limited himself to describing the position at the oil fund as his “dream job” and “a higher purpose than just working in a normal bank. You should be proud of working for your country,” he says.

But his countrymen are already unsure what he can do for them. He will enter the role a “significantly weakened figure,” Kapoor notes, with diminished power to take on bureaucracy and a weakened ability to bargain for the oil fund to have more discretionary powers.

“It’s bad for him personally because far too much time will be spent twiddling his thumbs,” Kapoor says. “But it’s even worse for the fund.”