Shortly after Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos headlined a $5 million equity round in the scrappy young media brand Business Insider in 2013, its editor and co-founder, Henry Blodget, jumped on a commercial flight to Seattle, squeezed his lanky frame into a coach seat, and set off to pay homage to his new angel investor.

It was an intoxicating moment for Blodget, a onetime star Wall Street analyst whose career in the financial industry ended in disgrace when, in 2003, he settled fraud charges related to several companies he had analyzed during the late-1990s tech bubble.

By 2013, a decade had passed, and Blodget’s days as an analyst were arguably best remembered for his bullish views on Amazon, whose stock price he predicted in 1998 would rise from $240 to $400 a share — which it quickly did.

Amazon now trades north of $3,000, and Blodget’s Amazon call is seen on Wall Street as one of the most prescient in the history of technology. Yet it had been controversial when Amazon was awash in red ink. Even in March 2014, when Bezos led another round in Business Insider, this time for $11.9 million, Amazon still had plenty of high-profile detractors.

Not Blodget.

“He didn’t travel eagerly,” recalls Julie Hansen, Business Insider’s president and chief operating officer at the time. “He scrutinized every trip, but he couldn’t get on that plane fast enough to Seattle when the opportunity arose.”

During the long flight to the West Coast, Blodget remembers writing a single-spaced, multipage memo explaining why he thought Business Insider could reach $50 million to $75 million in annual revenues.

Those numbers “seemed gigantic at the time,” he says.

But Bezos was sanguine.

“I think you can get a lot bigger than that!” he told Blodget, who now admits, “As usual, he was right.’’

The Business Insider editor hoovered up the billionaire’s advice. When he returned from the visit to Amazon headquarters, says Hansen, “Henry was like Moses coming back from the mountain with the tablets.”

One important takeaway for the young media site, Blodget said in a recent interview with Institutional Investor, is “you can take a much longer view than what’s happening right now.”

“Amazon is about a seven-year view,” he says. “Most public companies, it’s a one- to two-year view. And, as it turns out, they’re very risk-averse. Jeff and Amazon are willing to make a long-term bet and are very willing to be misunderstood for a long time while they’re building toward that.”

The former analyst speaks from firsthand knowledge of the short-term mind frame on Wall Street — a mind frame he rejected in the creation of Business Insider.

Now 13 years old, Business Insider — which, like Amazon, had a plethora of doubters along the way — was still in its relative infancy when Bezos came on board. But in 2015, the startup was sold to Axel Springer, one of Germany’s biggest media companies, which was keen to build a digital media presence in the U.S. With that backing, and Blodget at its helm, Business Insider has ramped up to be one of the most vibrant — and popular — media companies in the world: By December 2018, it had more than 98 million monthly unique visitors in the U.S., ranking second behind CNN in the Comscore general-news category, according to Business Insider. That year, Business Insider hit $100 million in annual revenues and turned a profit, Axel Springer reported.

With the media world now in turmoil, Blodget’s sale of Business Insider to Axel Springer looks like sheer genius — or at least serendipity. Buffeted by both secular business trends and immediate pandemic-related pressures, venture-capital-backed digital peers like BuzzFeed and Vox Media are laying off employees, tabloid stalwarts like the New York Post have dismissed veteran reporters, and even the future of storied publishing empire Condé Nast is uncertain.

There are no layoffs at Business Insider, which is now part of a larger site called simply Insider — a nod to a new expansion of its reporting focus beyond the business world. In fact, Insider is hiring: More than 30 editorial job listings for the U.S. are currently posted on Insider Inc.’s website, as well as 11 internships and fellowships. And that does not include jobs in areas like its new reviews section, nor openings on the data and business side.

Blodget wants to double Insider’s staff, which currently includes 500 journalists, and have 1 million paid subscribers in five years. He also wants to reach 1 billion global readers a month, up significantly from an audience of about 275 million now. The current number, the company says, includes “half of all U.S. millennials on the internet.” Yet he skillfully dodges a question about Insider’s desires to overtake giants like The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Washington Post. “We don’t want to replace anybody,” Blodget says.

But make no mistake: His ambitions are absolutely vast, as others at Insider quickly admit.

“We want to be better than all of them and more beloved than all of them and have more subscribers than all of them and have more impact on the world than all of them,” says Nicholas Carlson, Insider’s global editor-in-chief, who, as one of Blodget’s first hires, is considered his protégé. “I tell everybody we hire that’s the goal and that’s the ambition. That is very audacious.”

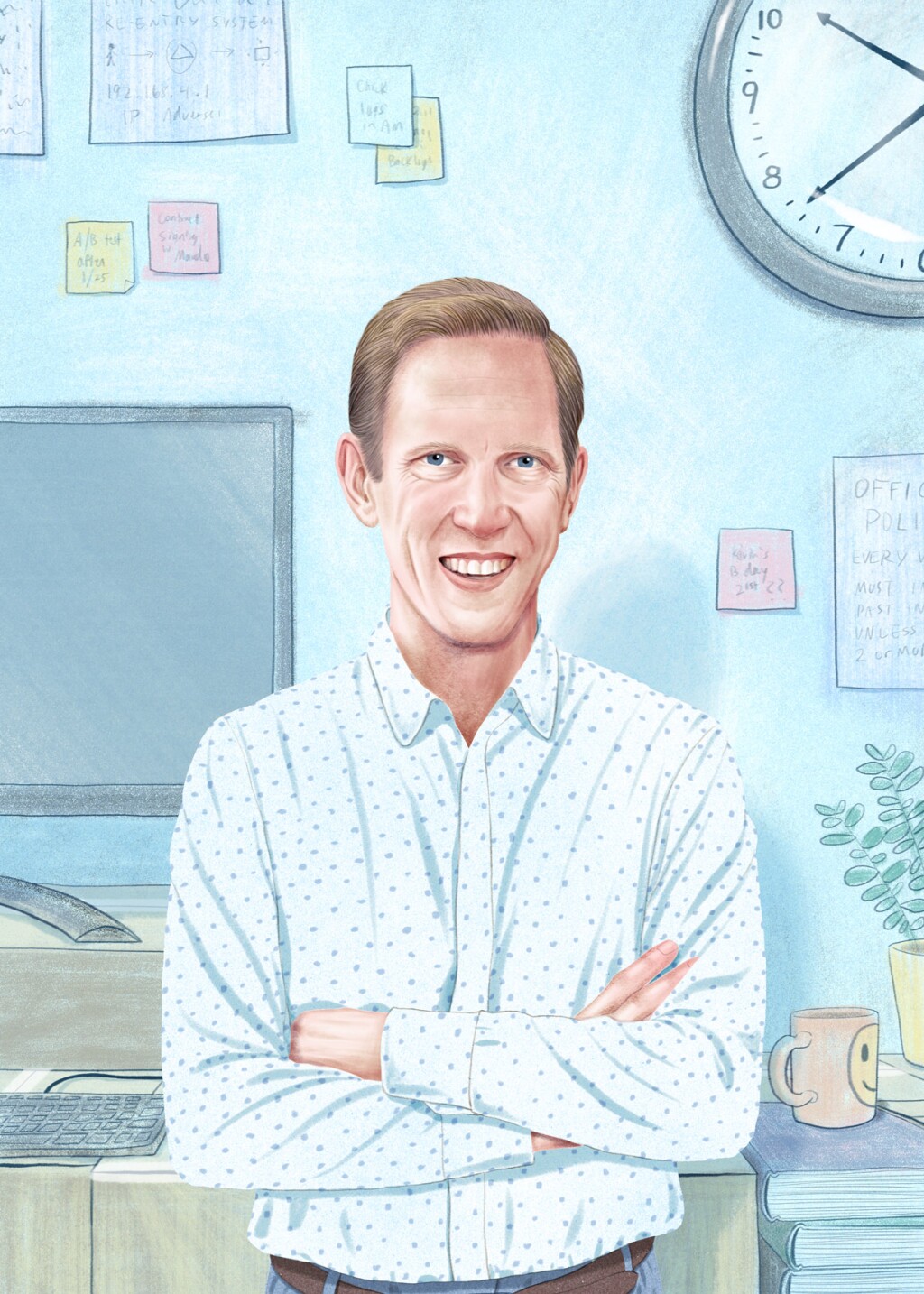

For Blodget, who lives in the Park Slope neighborhood of Brooklyn, that can mean a cedar-shake family home near the Berkshire Mountains. That’s where he Zoomed into our interview, wearing a navy pullover, his chestnut hair slicked back as if from a recent shower.

Tall and slim at 54, Blodget exudes a casual, youthful vibe — an attribute that has allowed him to work well with a much more junior staff, especially in the early days of Business Insider, where a freewheeling culture gave its reporters wide latitude to write about their passions.

He is also the rare newsman with a prior Wall Street career in sell-side research and deep knowledge of the technology startup world, a fact that’s key to understanding just how Insider, almost alone among recent startups, has managed to become a top media brand in the digital age.

Analyzing Amazon’s success was certainly part of it. “The most important thing Jeff just harped on from the beginning was customer obsession,” says Blodget. “We have been focused on our audience and serving our audience. I think lots of companies get distracted with what competitors are doing, or in our industry, sometimes people get distracted by journalism — as opposed to serving an audience with journalism.”

Such a claim might make one immediately think “clickbait,” and that’s definitely what Business Insider was accused of offering early on, with its obsession with digital views — a big TV screen on display in its Manhattan lobby showed which stories were the most read at any moment and how many views they had. With its relatively inexperienced staff, Business Insider also depended on aggregating stories from other sites — regurgitating those that appeared behind paywalls at other publications — and it excelled at catchy listicles like “The Sexiest Men on Wall Street.”

The attention to the SEO principles of headline writing and distributing content on places like Facebook and Google helped push its content far and wide. “There’s a lot of news out there that people don’t know they want to read,” says a former Business Insider reporter. “The whole mindset at BI is that the traditional media doesn’t know how to do digital. They don’t know how to make readers want to read something.”

These days, the original staff has matured, and Insider has hired experienced journalists and editors, all of which enables it to go deeper into subjects and transition from a site supported by advertising to one at least partially supported by paid subscriptions.

“We feel like our reach is big enough,” says Blodget. (Insider says that in May, its Comscore U.S. general-news rank fell to fourth, behind CNN, The New York Times, and NBC News, with 110 million monthly unique visitors, as it continued to put more content behind a paywall.)

“Really, what we’re focused on is engagement,” he says, naming a metric that measures how much time a reader spends on a story. Impact — a softer measure of such things as how often Insider is mentioned by other media — has also become important.

Blodget insists that just collecting eyeballs was never what Insider was about anyway. “It’s not giving people what they want, which, unfortunately, if you measure that just by raw views, you always just immediately redirect everything to celebrity gossip news, because that’s the thing that is read by the most people in the world.”

Instead, he says, Insider’s mission is “to inform and inspire.”

It’s a decidedly optimistic view that, colleagues say, fits with Blodget’s upbeat personality and tech mindset — and which might seem remarkable given his past regulatory troubles.

“The world, contrary to what you see on the news a lot of the time, actually is for the most part getting better all the time,” Blodget says. “We have big problems to solve, but the only way we’re going to continue to get better is by solving those problems.” Insider wants to write about those problems — and the people solving them, he says.

But make no mistake. Blodget’s experience on Wall Street gave him business savvy — and deep scars.

In one case, Blodget gave digital company GoTo.com a satisfactory rating in a 2001 Merrill report, saying investors should hold on to its shares. But the SEC singled out his GoTo.com rating as an example of fraud: When the regulator combed through Blodget’s emails, it found that after an institutional client had asked, “What’s so interesting about GoTo except banking fees????,” Blodget had replied, “Nothin.”

It was not supposed to be so for a child of privilege. Blodget grew up on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, the son of a banker, and attended Phillips Exeter Academy before going to Yale, like his father before him. In his college days, Blodget was a student of history who was less likely to be found partying than, as former classmate Hansen puts it, “in a very serious discussion.”

After graduation, Blodget flirted with a career in journalism — including a brief stint at CNN — before landing on Wall Street in the early 1990s, where he quickly excelled. Then the dot-com bubble burst, and the conflict of interest between research and investment banking on Wall Street suddenly exploded into view.

It wasn’t a new phenomenon. “What was interesting to me was that that conflict of interest had been talked about openly for more than a decade,” muses Blodget. “It was so out in the open that I think nobody in the industry really thought about it. It was really a very startling experience to have this . . . be held up as something that was secret.”

Blodget settled the case, without admitting or denying guilt, for $4 million, and was banned from the industry for life. In rebuilding his personal brand, Blodget has never shied away from talking about that unpleasant chapter. “It was formative and traumatic,” he says.

But he defends his behavior. “I never would have done the job if I thought that I couldn’t maintain my integrity in doing it,” he insists. “But it didn’t mean there wasn’t a lot of pressure.”

Many on Wall Street and elsewhere believe that Blodget was unfairly singled out. “Henry was the fall guy for what were a lot of common institutional practices,” says Jacob Weisberg, who helped Blodget launch his comeback by hiring him to cover the Martha Stewart insider-trading trial for Slate when Weisberg was its editor-in-chief. “He was not in any way an outlier or a bad actor. Everything I’ve learned since then has confirmed that Henry is a very ethical person as a journalist.”

The lessons learned from his brush with the authorities, Blodget says, taught him to be as transparent as possible. “You need to be able to explain exactly the way things work to people who have no particular knowledge of the industry,” he says.

The debacle also showed him that the world could change in a nanosecond, as the tech crash itself memorialized.

“I saw many companies that seemed to be extremely strong just get obliterated in the downturn. There were companies that were huge that went out of business because they signed long-term leases in ten countries or what have you, and suddenly, they couldn’t raise capital and nobody was buying their products and they literally went bankrupt. That was a very scarring and memorable experience,” he says.

When Blodget began his new life as the editor of Business Insider’s predecessor blog, Silicon Alley Insider — where he continued his trenchant analyses of tech companies — he took nothing for granted. “It taught me to never expect that a good time is going to continue forever. Be ready for a downturn. Have an idea of how you’re going to get through it.”

“He’s not afraid to fail,” notes Weisberg. “You see that with what he’s done with Business Insider. I think someone else would have said to himself, ‘Who are you? You’ve written some articles; you’ve never been an editor or never been a publisher.’”

If Blodget ever had any such thoughts, he didn’t listen

“When we raised a little bit more capital, we said, ‘Okay, we’ve got another year to make that progress.’ And we didn’t come in with a very fixed idea. We came in with a very experimental mindset — figure out what’s going to work,” Blodget says. For example, Blodget wanted to expand into video, but started out with a single camera and shot the videos in the office. When videos took off, he bought better equipment.

Blodget’s experimental approach took the company through seven rounds of VC financing, raising an estimated $55.6 million, with backing by such big names as Marc Andreessen, Kenneth Lerer, and Stuart Ellman, in addition to Bezos.

It also caught the attention of Axel Springer, a German publisher of newspapers, including Bild, the influential German tabloid, and its older sibling, Die Welt.

Berlin-based Axel Springer realized it needed to embrace the digital transformation of media to survive and, in 2012, sent several top executives to Silicon Valley to immerse themselves in tech culture. Starting in 2014, it began making minor investments in various digital content companies “to learn how the U.S. market is working,” says Jan Bayer, who oversees all of the company’s U.S. investments and is now the chairman of the board of Insider Inc.

Then it discovered Business Insider. On February 2, 2015, Axel Springer was part of a $25 million VC round for the brand and soon learned that the whole enterprise was for sale. “The door opened, and it was clear that Business Insider [was] looking for a major investment. We were, until then, a small investor, so we knew the company very well. We knew Henry, we knew the team. For us, it was pretty clear that the fit between Axel Springer and Business Insider [was] very well.”

Blodget’s financial background and experience as a journalist was an “ideal combination,” says Bayer. “As an analyst, you learn to understand market trends. He’s pretty good in anticipating the way markets are developing. This combination of being ambitious, being in journalism, and also being a businessman — that was fascinating.”

As for Blodget, finding a corporate parent was key. “We knew we would want to be owned by a media company, because it’s a different growth trajectory,” he says. “It’s ultimately a different mission than venture capital.”

And because the German company had no U.S. footprint, Business Insider would not face the cutbacks common to so many mergers. “It was not, ‘We’re going to find a way to cut and synergize you.’ It’s, ‘How can we use you and build in the United States?’” says Blodget.

It happened quickly: By September 29, 2015, Axel Springer had sealed a deal to buy 88 percent of Business Insider for $343 million, upping its ownership stake to 97 percent. The remaining stake belonged to Bezos, who was bought out the next year.

A year ago, Axel Springer made another big move when it sealed a deal with KKR, the private-equity giant, which would buy 42.5 percent of the company and take it private. (KKR ultimately ended up with a 44.9 percent stake in Axel Springer.)

By the time of KKR’s investment, Insider was one of Axel Springer’s fasting-growing segments, with operations in the U.S and the U.K. and licenses with franchisees who now publish Insider in more than a dozen countries and eight languages. Axel Springer said last summer that Insider’s revenues had grown more than 33 percent per year since 2015.

Insider also moved to a subscription model. In 2013, advertising was 85 percent of its revenues, according to a profile of Blodget in The New Yorker. Today, only half comes from advertising, says Blodget. The rest is subscriptions, not just to the news product but also to Insider Intelligence, a unit announced mid-pandemic, in May, following the merger of Business Insider Intelligence, its data-driven market-research unit, and eMarketer, a market research firm owned by Axel Springer.

While 2020 has been, well, 2020, news is suddenly in demand. “We’re in a good position,” Blodget said in an April virtual town hall. “The world has never had a greater need and interest of trustworthy, fast, and relevant information about what’s going on.”

Adds Bayer: “We outperformed the market, especially during the corona crisis. I mean, subs are going through the roof.”

But the next chapter will be Insider’s — and Blodget’s — biggest challenge yet.

Although he won’t comment on the amount, Blodget acknowledges that some of his equity was rolled into options that vest over ten years.

He seems more than content to stick around.

“I feel incredibly lucky with where I’ve ended up,” he says. “I feel like we are still at the early stages of building out what the long-term vision is, and I really think we can get there with a lot of hard work and a lot of luck and a great team and everything that’s got to go into that.”

Blodget is not a crusty old-school editor, with the cynicism and world-weariness that can go along with it. Nor does Insider have the same sense of public service as legacy newspapers — which Blodget does not deny. And he has waded into journalism’s more contentious arenas carefully, and slowly.

Carlson — who took over Blodget’s job as editor-in-chief after the sale to Axel Springer pushed Blodget into a broader strategic and managerial role as Insider CEO three years ago — says the SEC debacle “100 percent” made Blodget cautious. “Going through the wringer the way he did has made him a much, much better journalist and hopefully has made us a better newsroom, because it means that we pause, think about the people we’re being critical of, give them every chance to respond.”

That said, Insider’s ambition to be a journalistic heavyweight is going to be an expensive and enlightening endeavor.

Two fairly recent initiatives give a clue. One is an investigative unit headed by veteran journalist John Cook, formerly the editor of both Gawker and The Intercept, that was launched a little over a year ago. (One former BI reporter says before this hire, editors “discouraged pursuing longer-term investigative pieces. You don’t know if they’ll pan out.”)

Then in March, Insider finally established a D.C. bureau to cover politics, headed by former senior White House Politico reporter Darren Samuelsohn, and is looking to hire reporters.

As Insider moves into the wider media fray, Blodget also finds himself grappling with its biggest debates — like the ones that followed the protests catalyzed by the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis earlier this summer. One controversy involved The New York Times op-ed penned by Republican Senator Tom Cotton, who advocated sending in the military to quell protests. In the midst of the racial reckoning roiling the country, the uproar over the op-ed’s publication ended in the departure of New York Times editorial page editor James Bennet, who happens to be a longtime friend of Blodget’s.

“The industry is looking at this and saying, ‘Okay. What is our mission? What’s the right thing to do?’ And we’ve talked a lot about it at Insider and I can say that we’re not a political journalism organization,” says Blodget, who seems aghast that running that op-ed was “a fireable offense.”

Insider doesn’t publish many op-eds, so it’s easy for Blodget to say he doesn’t know if it would have run the Cotton piece. However, Carlson — who is 37 — adamantly states that the answer is no.

And that’s the rub. The younger generation Insider wants to appeal to is far more progressive than its elders, and Blodget is attempting to execute a balancing act as he woos youth while holding on to readers of all ages and political persuasions. (A few weeks ago, Insider announced it would hire a managing editor to “focus on making our newsroom more diverse.”)

Blodget, of course, has his own opinions — and he’s not been shy about expressing them. Earlier this year, David Plotz, who had been Blodget’s immediate editor at Slate, got a call from Blodget.

“When Covid hit, Henry and I started talking and he wanted to write a newsletter. He wanted a writing partner,” says Plotz.

In another new direction for Insider, since April the two men have been churning out a daily newsletter, giving their short takes on the controversies of the day. A recent one, titled “This Is How Democracy Dies” and penned by Blodget, argues that President Trump’s move to send federal troops to Portland, Oregon, was evidence that “this latest step in the transition to authoritarianism is complete.”

That’s a bold statement from Blodget. But whatever directions Insider takes, Blodget’s motivations are clearly not to be a political scold. They are instead perhaps best explained by Carlson, who likes to tell a story from his first meeting with his boss.

“Henry said when he learned that he was doing the right thing was when his wife told him that she could hear him laughing while he was writing in the basement,” Carlson remembers. “That joy in storytelling, getting a kick out of it, has been for me the kernel.”

“This is someone who’s in it to write stuff that will make people go, ‘Whoa!’ or ‘Hey!’ or ‘Ha ha,’” Carlson says.

“To feel . . . something.”