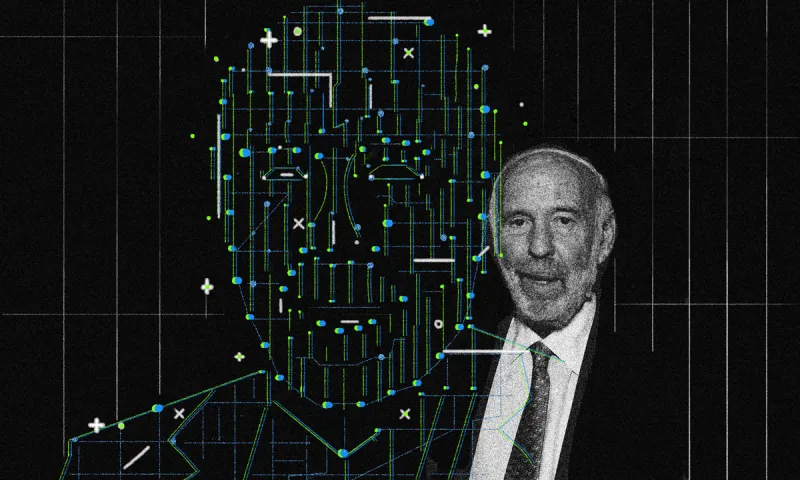

Illustration by II/Photo of Jim Simons

(Amanda Gordon/Bloomberg)

Explosively, professor Bradford Cornell’s recent brief analysis of the performance of Renaissance Technologies’ Medallion fund states that “to date, there is no adequate rational market explanation for this performance.”

I find this conclusion interesting — not because of its contribution to our understanding of the Medallion fund’s performance (such efforts have devolved into a parlor game), but because it accidentally reveals an implicit worldview that, upon reflection, is a root cause of the dismal record of active management.

This belief rests on the conceit that investing is essentially a human activity — and therefore human reason must be able to explain the results of such activity.

There is a continuum of expressions of this worldview, ranging from the dogmatic assertion that active investing must be based on either cash flow analysis or short-term price movement to authoritarian claims that there can be no investment activity without human talent.

Through dictatorial educational programs and a homogeneous workforce, we have reached a point where this perspective is unquestionably accepted. This acceptance allows us to pretend that everything worth knowing is already known and in use, making any alternative unimaginable.

The problem is that such doctrinaire views have consequences.

However, the “discovery” of the Americas presented a challenge: It revealed that the world was not known in its entirety (hence the term “New World”) and that the inhabitants of this new region could not be accounted for in Noah’s genealogical tree.

This challenge was of immense consequence because this worldview was based on the word of God, expressed as sacred scripture.

The scripture says that the gospel has been preached to all nations — but these indigenous people knew nothing of the gospel or of Christianity. To rationalize this discrepancy between fact and scripture, a group of theologians and scholars reached the logical determination that those people were not truly human.

This rational conclusion provided intellectual justification for the mass exploitation and forced enslavement of indigenous people. In an attempt to reconcile their existence and that of the New World itself with the existing worldview, Pope Paul III issued a papal bull that said unambiguously that “the Indians themselves are truly men.” That statement set in motion a shift to a new understanding of human rights.

In investing, we, too, have our own “scripture” that grounds our perspective, and, though not revelatory, it has been unshaken for the past 60 years.

For example, since Michael Jensen’s 1968 landmark study of the performance of 115 mutual fund managers, we have held the view that active management cannot consistently provide returns better than a relevant passive proxy.

Yet the “extraordinary” and “unprecedented” performance of the Medallion fund presents us with a phenomenon that contradicts this fundamental belief. “In forty plus years of reading hundreds of papers on investment anomalies, including some that benefited from data snooping and ex-post selection bias, I have never seen any performance approaching that reported by Medallion,” professor Cornell concluded in his paper.

He implies that human knowledge and action could not generate this kind of performance. Dismissing fraud as the explanation, we are left with the possibility that the source of the performance is, to use the term of the 16th-century Catholic theologians, “not truly human.”

But non-human investing simply is not possible within our current ideology. Non-human investing and, more generally, non-human knowledge require an alternate worldview.

He writes: “Traditional AI programs operate according to hard-coded rules [created by humans], which restrict them to working within the confines of what is already known. But a new wave of AI systems, inspired by neuroscience, are capable of learning on their own from first principles.”

These systems do not use human data or human expertise in any fashion — and, precisely because of that, they are not encumbered by those constraints. They are “able to create knowledge itself.”

Other knowledge-based verticals (e.g., medicine) have used these new systems (e.g., deep learning and deep reinforcement learning) to achieve superhuman results — results that exceed those that can be achieved with human knowledge and expertise.

Even as many investors might acknowledge that these models could achieve such superhuman results within narrowly defined applications (such as playing board games and reading CAT scans), they dismiss the possibility that the same systems could be used successfully to build self-learning investment processes by claiming that markets are simply too noisy and too unpredictable.

Not only are these claims unsupported by any empirical evidence — they are grounded in a distinctly human-centric view of markets. After all, “noise” and “predictability” are human constructs.

This argument against an alternative worldview reminds me of Stephen Jay Gould’s remark that “we modern scholars often treat our professions as fortresses and our spokespeople as archers on the parapets, searching the landscape for any incursion from an alien field.”

Yet we live in a time when the defense of our beliefs threatens our future — client dissatisfaction with the current iteration of active management is so great that PwC estimates that “by 2025, at least 20% of fund managers will be acquired or eliminated.”

Our industry has faced and responded to a similar threat in the past. James Vertin, one of the apostles of our investment scripture, wrote in 1974:

Current and prospective customers are increasingly suspicious, hesitant, and downright skeptical that professional investment management can consistently provide benefits that justify its cost . . . the dissatisfaction is pervasive. . . . [T]hey are afraid of us, and what our methods might produce in the way of further loss. . . . It doesn’t have to be that way. . . . There exists for us through utilization of the full body of knowledge now available to our profession the opportunity to create a viable alternative to the grope approach. By moving on from the point at which we have been stalled for so long, we can significantly improve our investment management product and salvage our reputation.

Vertin was maligning the investment worldview of his day — the “grope approach” that used undisciplined investment decision-making founded on “conventional wisdom” — and advocating the adoption of a new idea built on “rationality,” arguing that this alternative could save the profession and help “our increasingly unsatisfied and disgruntled customers.”

Thanks to Cornell, we see today that the very “rationality” Vertin envisioned as the industry’s savior has created artificial boundaries of knowledge and has itself become the cause of the struggles of traditional active management and the source of our own increasingly unsatisfied and disgruntled customers.

In a perverse way, the Medallion fund’s singular, unexplainable performance may be the very catalyst our industry needs to save itself.