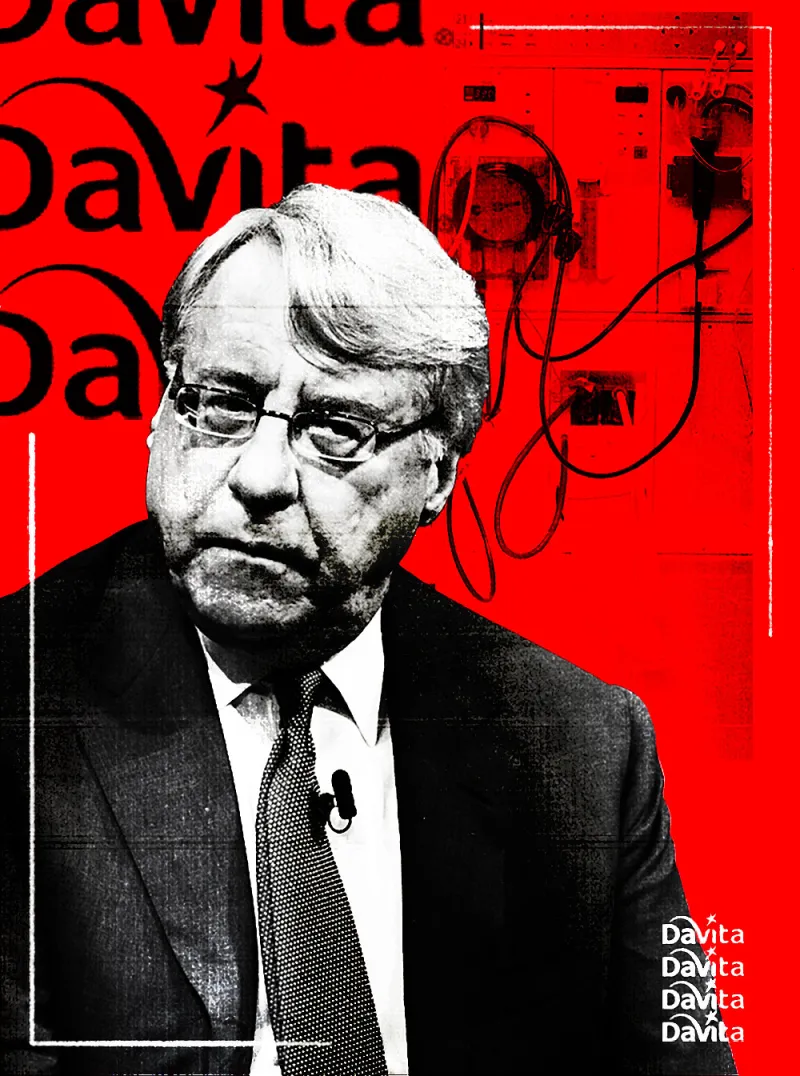

Jim Chanos.

(Illustration by II; Misha Friedman/Bloomberg)

When former hedge fund manager Ted Weschler joined Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, he brought with him knowledge of DaVita, a kidney dialysis provider. Between the September 2011 announcement of his hiring and his early 2012 start date, the company appeared in Berkshire’s portfolio.

It has become one of the latest known targets of prominent short-seller Jim Chanos, a man who makes a living betting against companies.

So far this year, Chanos is on the losing side of the bet. DaVita’s market value climbed to $9.4 billion on December 3, with its shares soaring 40 percent since the end of 2018. The stock’s rise includes a 21 percent jump since Chanos, the founder of Kynikos Associates, first spoke publicly about his wager against the company on September 19 at the Delivering Alpha conference in New York.

There, Chanos pointed to what he alleged to be a massive insurance scam. According to Chanos, DaVita uses its relationship with the American Kidney Fund — a charitable group that helps people with kidney disease pay for lifesaving care — to profit by moving Medicare patients into more expensive commercial insurance.

The company’s growth is challenged in the near term because DaVita has “far too much earnings derived from its relationship with the American Kidney Fund,” JPMorgan Chase & Co. analyst Gary Taylor wrote in a November 5 research note. The charitable fund, which helps cover patients’ commercial insurance premiums, receives major funding from DaVita and rival dialysis provider Fresenius Medical Care, according to Chanos.

“It is a strange situation, no question,” said Matt Larew, an equity analyst at William Blair & Co. who covers DaVita, in a phone interview. “They get paid substantially more by private payers. And then they happen to be big-ticket donors to the AKF.”

DaVita benefits from the relationship with the American Kidney Fund because the reimbursements it receives from commercial insurers is much higher than what it gets from Medicare, according to analysts who follow the company. While controversial, it’s not illegal, they say.

“It’s just the way it works,” said Larew. “If they change the rule, I’m sure DaVita will operate by the new rule.”

While Larew doesn’t see DaVita doing anything “unethical,” he said the company would be more vulnerable to a rule change than rival Fresenius, partly because it’s a “pure-play” dialysis company.

Commercial revenue from dialysis is no doubt important to DaVita. “The payments we receive from commercial payors generate nearly all of our profit,” the company said in its 2018 annual report.

“They’re essentially 100 percent exposed,” said Larew, whereas Fresenius runs a business that’s “a little bit broader in nature.”

But Berkshire, a conglomerate that runs an insurance business alongside other holdings, doesn’t appear to be backing down from its investment in DaVita. That pits Chanos against the firm built by chairman and chief executive officer Buffett, a billionaire who has long earned wide respect from investors for his integrity — as well as his success at making such bets.

With DaVita’s shares trading around $72, Berkshire’s stake is worth about $2.8 billion. That’s up from around a half billion dollars in early 2012, when the firm revealed a much smaller position, regulatory filings show. A less significant interest was first established by Berkshire during the final three months of 2011 — in the runup to Weschler’s start date — but the wager wasn’t Buffett’s, the firm said.

The bet is “a portfolio holding of one of our two portfolio managers (not Warren Buffett),” Debbie Bosanek, assistant to Buffett, said in an email to Institutional Investor. “Our two portfolio managers are Todd Combs and Ted Weschler.”

Combs joined Berkshire in 2011 from hedge fund firm Castle Point Capital Management, while Weschler started working for Buffett in 2012. Weschler previously was a managing partner at Peninsula Capital Advisors, the hedge fund firm he founded in Charlottesville, Virginia, and shuttered in 2011.

DaVita was a holding of Peninsula in 2011 — the year Weschler won a charity-auctioned lunch with Buffett for a second time before joining Berkshire.

In his 2012 annual letter to shareholders, Buffett said Berkshire “hit the jackpot” with new investment managers Combs and Weschler. They “have proved to be smart, models of integrity, helpful to Berkshire in many ways beyond portfolio management, and a perfect cultural fit,” he said in the letter. Buffett also noted stocks detailed by Berkshire in its annual reports would now include investments made by Combs and Weschler, either together or alone, provided the value met the firm’s dollar threshold for the year.

DaVita appears for the first time in Berkshire’s annual reports in 2014. At the end of that year, its 8.6 percent stake in the company was valued at $1.4 billion, making DaVita one of the firm’s 15 largest common stock investments. The report listed the purchase price as $843 million.

“I just can’t understand why Berkshire Hathaway would be promoting a company that’s gaming the insurance business as much as DaVita is,” Chanos said at the Delivering Alpha conference, co-hosted by II and CNBC in September. DaVita is “running an insurance scam,” he alleged, calling it “a very bad look for an insurance company like Berkshire Hathaway.”

Buffett’s assistant said in an email that Berkshire’s portfolio managers “don’t do interviews” and did not respond to a subsequent request for comment on Chanos’s allegation that DaVita is running an insurance scam.

The dialysis company was last listed among Berkshire’s biggest stock holdings by market value in 2015. It has not appeared in its annual reports since. Still, with more than a quarter of its shares, Berkshire is by far DaVita’s largest stakeholder, Nasdaq data show.

The patients are willing to move to commercial insurance because they’re told of better services, shorter wait times, and nicer facilities, Chanos alleged. Also, depending on their circumstances, the charitable American Kidney Fund will pay some to all of the premium tied to the private insurers, he said.

For DaVita and Fresenius, it’s a more profitable way to do business: They charge commercial insurers triple or quadruple what they get from the government’s Medicare and Medicaid programs, he said.

“Now, this is bad enough,” said Chanos. “But what really is interesting is that the two largest donors, at slightly less than 90 percent of the donations to the American Kidney Fund, are DaVita and Fresenius.”

Donations made by the two dominant dialysis providers have sparked concern over the potential for conflicts of interests, according to Jonathan Kanarek, an analyst with Moody’s Investors Service who covers Denver-based DaVita.

The concern is that their donations may be keeping people on more expensive forms of insurance so a provider of dialysis can make “multiples of what it would otherwise be paid by Medicare for the same level of care,” Kanarek said in a phone interview. “That’s what raises eyebrows in the industry.”

DaVita and Fresenius are permitted to donate to the American Kidney Fund, whose work helps them earn more, because they’re not the ones directing the charitable giving, according to Chanos. That distinction gives them safe harbor. “They just donate out of the goodness of their heart and, shockingly, they get this extra reimbursement,” he said.

DaVita says Chanos doesn’t understand its operations.

“Statements from this short seller contain false and misleading information and reflect a poor understanding of our business and our industry,” Courtney Culpepper, a spokesperson for DaVita, said in an emailed statement. “Contrary to his claims, charitable assistance is a longstanding financial safety net for a small percentage of kidney care patients who use it to afford their insurance plan, with the majority of patients using it to support their Medicare primary or secondary premiums.”

The spokesperson added that “this assistance helps ensure they have continuity of care for life-sustaining treatment and access to transplantation.”

American Kidney Fund spokesperson Alice Andors said by phone that “our mission is taking care of patients — and that’s what we do.” She declined to comment on allegations that DaVita is running an insurance scam, saying related statements can be found on its website.

One such statement was made in response to California congresswoman Katie Porter’s call in July for an investigation into the dialysis industry’s practices. She raised concern that the country’s largest dialysis providers may be “lining their pockets at patients’ expenses” by using financial influence over the American Kidney Fund as donors.

The nonprofit group responded in a July 24 statement that it provides an “essential safety net for low-income end-stage renal disease patients” and that “internal firewalls ensure that dialysis providers have no say in whether AKF will assist their patients.”

Andors did not reply to an email seeking comment on the size of the donations made by DaVita and Germany’s Fresenius to the American Kidney Fund. Fresenius’s press desk in North America also did not respond to an email and phone call seeking comment on its donations to the charity and allegations of an insurance scam benefiting its bottom line. Matthias Link, a spokesman for Fresenius in Germany, did not reply to an email requesting comment.

Amid heightened concern over the potential for conflicts of interests in the dialysis industry, S&P Global Ratings credit analyst Ji Liu said it’s important to remember the life-saving nature of the business.

“It would be hard to have a very unfavorable regulation against the industry without potentially jeopardizing patient access,” Liu said in a phone interview. “There are patients who do need this to survive.”

“It’s always interesting, in my world, when one of your biggest customers sues you for fraud,” Chanos said at Delivering Alpha. “And this spring, Blue Cross of Florida sued DaVita.”

In May, Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Florida and Health Options — collectively known as Florida Blue — filed a complaint against DaVita for allegedly engaging in a “deceptive and illegal scheme” by making donations to the American Kidney Fund that are then used to buy commercial health insurance coverage for its dialysis patients. The company bills insurance companies such as Florida Blue for their services when the patients could instead be covered by cheaper Medicare or Medicaid programs, the insurer alleged in the complaint, filed in the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Florida, Jacksonville Division.

“DaVita used its considerable resources to either steer patients who were eligible” for Medicare or Medicaid into Florida Blue’s commercial health insurance, or keep them enrolled in plans they did not need or could not afford. That way, they could reap higher payments from the insurer, according to the lawsuit.

“Through this scheme, DaVita has damaged Florida Blue to the tune of tens of millions of dollars over at least the past several years,” the insurer alleged in the complaint. DaVita denied, in a court document filed in October, that it engages in the “deceptive and illegal scheme” alleged by Florida Blue.

“The challenge for any dialysis company, DaVita included, is to continually replenish the number of commercially insured patients that it treats,” said Kanarek of Moody’s. “Medicare is not profitable for dialysis companies.”

But commercial insurers would naturally prefer that patients who are eligible for Medicare move to the government program as soon as possible. “For whatever reason,” some patients are opting to stay put, according to Kanarek. The American Kidney Fund adds “complexity” to the dynamic because it’s supported by industry donations and its financial assistance may allow patients to stay on their existing commercial plan longer, he said.

That can drive up costs in a healthcare system under broader scrutiny for being expensive, according to Kanarek.

Details of a separate lawsuit involving DaVita, filed by a whistleblower in 2016, were unsealed about four months ago.

The suit led to an investigation but did not result in any intervention by the Department of Justice, according to a document filed in July with the U.S. District Court for the District of Massachusetts.

The whistleblower’s complaint against DaVita, Fresenius, and the American Kidney Fund alleged the dialysis companies were receiving kickbacks through favorable treatment from the fund’s charitable giving. The recently unsealed case revealed the identity of the whistleblower to be David Gonzalez, a former employee of the American Kidney Fund. After 12 years with the nonprofit, in October 2015 Gonzalez allegedly was “forced out of the organization for questioning the practices” detailed in his lawsuit, according to the complaint.

“We now know that this suit was brought by a former employee who, prior to making this complaint, was terminated for cause,” LaVarne Burton, the American Kidney Fund’s president and chief executive officer, said in an early August statement. The nonprofit group “strictly adheres to the federal advisory opinion that governs our charitable premium assistance program,” she said. “We have in place strict safeguards and conflict of interest policies to ensure that.”

DaVita short sellers are down $190.7 million, or about 41 percent this year, with more than half of those paper losses posted during the first week of last month, according to Ihor Dusaniwsky, managing director of predictive analytics at S3 Partners. (Chanos and Kynikos didn’t respond to requests for comment on DaVita.)

The number of DaVita shares shorted this year has risen by 90 percent, Dusaniwsky said in an email. The firm’s data showed a total $533 million of short interest in DaVita on December 2.

DaVita’s shares had jumped 13 percent to $70.51 on November 6, the day after the company reported its third-quarter earnings. Investors who were short DaVita saw $83.4 million in mark-to-market losses, he said.

The company’s earnings in the third quarter beat expectations as Wall Street “almost certainly didn’t model” for the earnings contribution from calcimimetics — a type of drug prescribed to patients with kidney disease — according to a November 5 report from JPMorgan’s Taylor, who has a neutral rating on DaVita.

DaVita’s “one-time benefit” tied to calcimimetics will mostly disappear next year, according to S&P Global analyst Liu, who gives the company a speculative-grade rating of BB with a negative outlook. DaVita was able to buy the drugs more cheaply, helping its cash flow in 2019, Liu said.

“The bigger story is their reimbursement on their dialysis treatment,” he said. “There’s a weird dynamic.”

Ninety percent of DaVita’s treatment volumes are paid by Medicare, business in which the company “barely breaks even,” he explained. Ten percent of volumes are paid by commercial insurance, from which “the company earns pretty much all of their operating profits.” Liu said that’s because commercial insurers pay three to four times what taxpayer-funded Medicare pays.

“The treatment itself is the same,” he said, creating tension between the commercial insurers and the dialysis providers. There’s a limit to how long dialysis patients can be covered under private plans, though, as they will eventually be moved to Medicare regardless of their age, according to Liu. “Patients can only stay on commercial insurance for 33 months before moving to Medicare,” he said. “It’s just the law.”

S&P’s outlook for DaVita is negative partly because of its concern it could adopt a “more aggressive financial policy” that includes sustained debt levels of more than four times earnings despite deteriorating industry fundamentals, according to its November 14 report. For example, the company will have to navigate “persistent reimbursement pressure” amid heightened regulatory scrutiny, S&P said, as well as slowing growth in the number of people receiving dialysis treatment.

DaVita provided dialysis services to about 202,700 U.S. patients at 2,664 outpatient dialysis centers at the end of last year, according to S&P. Obesity and heart failure are among the chronic health conditions that lead to dialysis treatment, said William Blair’s Larew. While companies like DaVita naturally profit from extending the lives of patients with the dialysis they provide, kidney transplants make such treatments unnecessary. That may be behind the market’s slowdown.

DaVita is “struggling a little bit” to understand why growth is slowing in the dialysis market, Larew said. One explanation the company has provided is linked to the opioid epidemic. In a conference call, “they pointed out that the opioid crisis has increased the number of healthy kidneys on the transplant list because it’s killing younger, healthier people who have died from opioid overdose,” Larew said. DaVita isn’t saying that is “the” overall problem, he said, but the company is seeking to understand why the number of patients going into end-stage renal disease is slowing.

“If you’re in a space where your organic growth is limited to basically market growth, and that market growth is slowing, you’re in a tough spot from a topline perspective,” Larew said. However challenging for DaVita, or darkly tied to the opioid crisis, fewer people in need of dialysis because their lives are saved by kidney transplants is undoubtedly a positive development.

Other avenues for growth are also muted, according to analysts. As DaVita’s potential organic growth declines, expanding through large U.S. acquisitions in the dialysis sector is also unlikely, said Larew. Regulators likely wouldn’t approve a large purchase by DaVita because, alongside Fresenius, it is one of two dominant providers of dialysis treatment to patients with end-stage renal disease in the U.S., he explained. DaVita and Fresenius provide services to nearly 75 percent of U.S. patients in need of dialysis, according to S&P.

And of the two, DaVita is more vulnerable to industry headwinds.

“We view DaVita as a weaker credit compared with Fresenius due to smaller scale, lack of diversification, and higher leverage,” S&P said in its November 14 report. The analysts expect the company will rely more on share buybacks to reach the guidance it provided for its 2022 earnings per share at its capital-markets-day event in September.

DaVita doesn’t seem shaken.

“We remain confident in our long-term strategy,” Culpepper, DaVita’s spokesperson, said in an email. She said this was underscored by the recent guidance for 2022 revenue, earnings per share, and cash flow. Its capital-markets-day presentation shows the company expects earnings per share in 2022 will be $6.25 to $7.25, compared to $3.57 last year.

But in the meantime, DaVita faces political threats.

A bill signed in October by the governor of California will “lower the reimbursements to arbitrated rates for all dialysis patients” who receive subsidies from the charitable premium assistance program, according to the S&P report. While DaVita is fighting the legislation in court, the credit ratings firm said the harm to its operating income could increase should other states follow suit.

“They are spending extra money for advocacy costs,” S&P’s Liu said. But the cost of lobbying efforts hasn’t stopped them from increasing earnings-per-share guidance next year. “They’ve actually increased their EPS guidance for 2020,” he said.

Other disruptive proposals could arise from the U.S. presidential election in 2020.

“If we get Medicare for All, or a Medicare option, or the ACA is shut down due to the federal court ruling, this business model blows up completely,” Chanos said at Delivering Alpha. Although a federal judge in Texas deemed the Affordable Care Act, or ACA, unconstitutional last year, it remains U.S. law. Still, a legal battle over its validity could reach the Supreme Court through appeal, according to a November report from nonprofit news service Kaiser Health News.

Chanos cited other issues casting a shadow over DaVita and the kidney dialysis industry.

At the Delivering Alpha conference, he claimed there was “rampant use of opioids amongst dialysis patients.” They’re overseen by doctors and nephrologists “who should know better,” he said, pointing to a 2017 study from Paul Kimmel that cautions against overprescribing opioids to dialysis patients.

In a paper he co-authored that year, Kimmel — a program director with the Division of Kidney, Urologic, and Hematologic Diseases at the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases — found “high rates of both chronic opioid prescription and excessive dosing in the maintenance dialysis population.”

DaVita has been tested in the past. S&P likes the management team and their track record of successfully battling reimbursement pressures over the past two decades, according to Liu. “They come out of those battles okay,” he said.

For all the headwinds and allegations surrounding the kidney dialysis industry, investors aren’t fleeing DaVita. Instead, they pushed its shares to a series of new 52-weeks highs in November.

At least for now, that’s making Berkshire’s bet look good.