An arcane Wall Street newsletter still printed in hard copy hardly ever warrants a cameo in a Hollywood movie. But that’s exactly what happened in The Big Short, the blockbuster about the men who predicted — and profited from — the financial meltdown of 2008.

In the film two small-time investors are asked to leave the Manhattan office of JPMorgan — which had just dashed their hopes of getting the qualification necessary to trade credit default swaps — when one comes across some marketing materials in the lobby.

“Look at this — this guy says that the housing market is a giant bubble,” he excitedly tells his partner. Then, in a voice-over looking straight into the camera, the other intones, “This part isn’t totally accurate. . . . I read about it in Grant’s Interest Rate Observer.”

So did a lot of people.

Renowned for his erudite, witty warnings about the deadly effects of excess leverage, Jim Grant, the eponymous newsletter’s founder and editor, was among the first to raise concerns about the toxic mortgage securities swirling through Wall Street in the early aughts. Grant’s became so popular that one major newspaper even sought to buy it.

By the time of the crisis, Jim Grant, who had launched his newsletter in 1983 after a stint at Barron’s, was already a well-regarded figure in financial circles, where a subscription is a rite of passage in Wall Street firms and hedge funds.

“Grant’s got passed to me by my boss, and I’ve passed it on to the younger people on my staff,” says SkyBridge Capital co-founder Anthony Scaramucci, who began reading Grant’s when he went to work on Wall Street, at Goldman Sachs. “The baton keeps getting passed. It’s colorful and contrarian enough that people want to read it.”

Contrarian it is. Even before the financial crisis, Grant’s Interest Rate Observer had been ahead of the curve of every speculative mania and eventual bust since the late 1980s, when its savvy prediction of the implosion of the junk bond bonanza fueled by Drexel Burnham Lambert first put the newsletter on the map.

Over the past decade, however, Grant’s has been notoriously wrong on a number of high-profile issues, such as its 2011 prediction of inflation and, more recently, its bearish take on the biggest hedge fund in the world — Bridgewater Associates — which led to an unprecedented retraction on CNBC.

Such errors could easily have been career-ending for a lesser journalist. They also raise the question of whether Jim Grant is out of touch with the financial world in an era of rock-bottom interest rates and hot markets driven by index funds, ETFs, and black-box quants.

“He’s been a longtime hyperinflationist. Just massively wrong on the impact of quantitative easing, fiscal policy, everything,” says one macro money manager who has taken an opposing position. “I have no idea why he’s so revered.”

His loyalists, however, include some of the biggest names in finance, who often speak at Grant’s biannual conferences: Baupost Group’s Seth Klarman (this fall’s keynote), Elliott Management Corp.’s Paul Singer, Duquesne Capital Management’s Stanley Druckenmiller, Pershing Square Capital Management’s Bill Ackman, DoubleLine Capital’s Jeffrey Gundlach, and JPMorgan Chase’s Jamie Dimon, to name but a few. Even former Federal Reserve chairs Alan Greenspan and Paul Volcker have made appearances.

The fact is, whether Grant is right or wrong doesn’t seem to matter to his ardent followers.

“He is respected for his intellectual curiosity and his writing style. He’s a very witty writer, which is rare in finance,” says short-seller Jim Chanos, the founder of Kynikos Associates, one of Grant’s oldest friends on Wall Street and a conference regular.

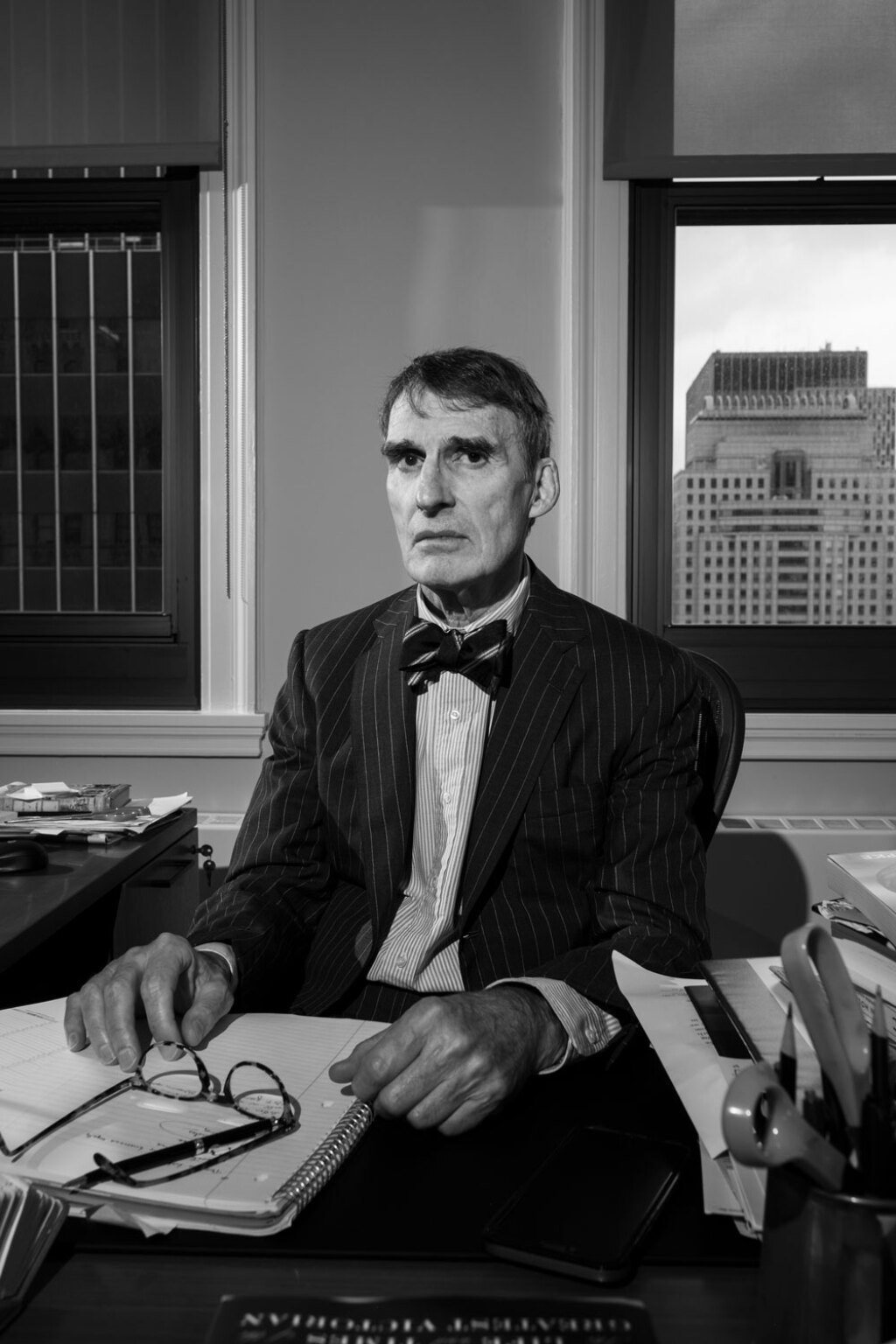

His job is not simply to take the world as it is, “but to speculate as to what it just might be, and to criticize institutions as they are,” Grant tells Institutional Investor in a wide-ranging interview from the newsletter’s somewhat spartan digs in the otherwise sumptuous Woolworth Building across from City Hall in downtown Manhattan.

At Grant’s none of the ostentation that makes that building a historical landmark — its ornate sculptures, mosaics, and other architectural touches — is visible. Instead, the most prominent decoration is a stuffed baby black bear that guards the Bloomberg machine.

It’s a fitting touch for Grant, who thinks the stock market is headed lower over the next year. But the editor insists he is not “the prophet of doom and gloom so much maybe as the prophet of reason. I can’t think of anything more uplifting.”

The stock market’s recent volatility may portend a breaking point. If and when markets do crack, Grant will surely be vindicated.

Then again, today’s world of cheap credit, private equity bonanzas, and unicorn IPOs — all targets of his scorn — may lead some people to think the editor of Grant’s is an anachronism.

Why the bow tie, one asks?

“Think how foolish I would be if I started to walk around with these over-the-shoulder bags and a two-buttons-opened shirt without a jacket, and talking about WeWork. I mean, seriously,” he says. (Grant’s, as is its wont, was among the critics of that company long before it chopped its prospective IPO price in half and postponed the date.)

Cheeky self-awareness aside, Grant — who is 73 — says his years of experience have made him less dogmatic, and he offers what appears to be something of a hedge. “I’ve come to appreciate just how many forks there are in the road, how many possibilities there are about tomorrow. Then too often tomorrow is just like today.”

But he is unlikely to change his perspective on too many things, like his unconventional view that the Fed should consider returning to the gold standard. “If I were running things — which, for better or worse, I seem not to be doing — I wouldn’t ram it down the throats of people,” he muses. “I’d say, ‘Look, here we have a monetary system in which the value of money is undefined.’”

Grant has long been critical of the Fed’s reliance on modern economic theory. “Modern central banking is pseudoscience,” he posits. “To base action on it is a species of recklessness that people will finally come to realize as such.”

His view of the ultimate result of such folly was cast in Grant’s August 9 issue in a clever headline — “Bonfire of the yields” — that channels author Tom Wolfe. Looking at the ominous specter of negative interest rates around the globe, he wrote with characteristically dry humor aimed at those in the know: “Aberrantly low rates set up the competition for yield that generates the distortions that sooner or later (as they say in Silicon Valley) breaks things.”

This critical view of the Fed may be rooted in an affinity for the Austrian school of economics, which Grant calls a “a school of thought that identifies as kind of a 19th-century liberal, kind of minimal intervention” in the markets. Grant identifies politically as a libertarian and at one time supported Rand Paul, who said he would name Grant the head of the Federal Reserve if elected president.

“That didn’t happen, did it? I lost track,” Grant teases.

Austrian economists Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek argued in the mid-1900s that a downturn in an economy unimpeded by state intervention cleanses excesses out of the system — a view that has come to represent the type of austerity policies shunned by many economists and progressive thinkers today.

At the same time, the Austrians are revered by many of Grant’s readers — conservative hedge funders like Singer, who is also the chair of the Manhattan Institute, a conservative think tank whose founder was so influenced by Hayek that it bestows an annual Hayek Prize on an author who advances the economist’s ideas.

In 2015, Grant — a history buff who just published a biography about 19th-century Economist editor and banker Walter Bagehot — received that prize for another work of history, The Forgotten Depression, which details the post–World War I U.S. recession of 1920–’21. In that case, the Fed initially raised interest rates instead of lowering them, the government stayed on the sidelines, and the slump was short-lived — although the recovery was eventually boosted by the Fed’s reduction in rates.

To be sure, Grant brings a historical knowledge to the understanding of financial markets that is rare these days among younger journalists. Yet history doesn’t always repeat itself, a point Grant is quick to acknowledge. “The thing with financial history is that it is very helpful except when it’s very unhelpful,” he avers.

Like many adherents to the Austrian school, Grant criticized the Fed’s quantitative easing, a market intervention that he argued would lead to inflation. It has not done so — leading some to question just why Grant’s ideas remain so popular among finance types.

In 2012, when Grant went to the New York Fed to explain what he felt the central bank was doing wrong, he joked that he had brought his food and beverage taster along with him. (No food or drink was on offer.)

Grant readily admits he got it wrong on inflation, even suggesting that his views may have been colored by getting his start in the 1970s decade of inflationary high interest rates. He launched Grant’s two years after rates hit their modern-day highs.

“What I missed in 2011 was the technical fact that the dollar bills that the Fed was creating effortlessly were not in circulation in the broad economy . . . but were locked up in the reserve accounts of the banks at the Federal Reserve system. . . . They did not make their way into the broad economy to finance the next inflation,” he explains.

Grant doesn’t concede that the scourge of inflation won’t return. But he acknowledges that today deflation seems to be the bigger concern, as evidenced by the trillions of dollars in negative-yielding government debt floating throughout the system — which he views as the biggest threat the markets now face.

Given these strong views, Grant has been called a perma-bear and a gold bug. He accepts the gold-bug moniker, noting that the portion of his personal investment portfolio he manages himself is invested in gold.

But Grant denies being a perma-bear, mentioning the bullish call on credit Grant’s made toward the end of 2008 — a particularly contrarian position that turned out to be accurate. Each issue of Grant’s, he says, strives to have a long idea as well as a short one. After almost 30 years of bearish takes on GE, for example, late last year Grant’s found that one GE high-yield perpetual preferred security was a buy. That, too, was a timely call.

Perma-critic might be a better term for Grant’s market views. Says short-seller Chanos, “The highest praise I could give him is that he’s been a bit of a perpetual cynic. And in finance, that’s not a bad place to be.”

And if he is revered by many hedge fund managers, value-minded Grant is an investor in only one hedge fund: the boutique, value-oriented Arbiter Partners, founded by Paul Isaac, a longtime friend who has also spoken at Grant’s investment conference.

To avoid conflicts, Grant says he doesn’t write about any of the stocks in Arbiter’s portfolio. And under Grant’s ethics policy, staffers must wait two weeks after publication before trading on anything mentioned in the newsletter.

Isaac, for his part, offers another rationale for Grant’s popularity. The editor’s relentless criticism of recent aggressive monetary intervention might get tiresome for some readers — one hedge fund manager says he pays no attention to Grant’s macro views. But those articles are “leavened with all kinds of shorter-term market commentaries, portraits of interesting and sometimes eccentric people, and particular investment ideas that are not directly related to macroeconomic themes,” notes Isaac.

Short-sellers and value investors, in particular, look more to the company-specific stories that dig into balance sheets. “What people pay for is not a sheet of paper with a ticker on it that says buy or sell. No, they pay for the analysis; they pay for the thought process,” explains Jim Bianco, founder of Bianco Research.

“In other words,” asserts Isaac, reading Grant’s “hasn’t felt like you’ve been riding around with Captain Ahab searching for the whale all this time.”

Born in New York City, he was raised in a middle-class suburb on Long Island. His father, a Juilliard-trained musician who had once played in the Pittsburgh Symphony, worked for drum and guitar manufacturer Fred Gretsch Co., where he was the firm’s liaison to the jazz world. Trips to Birdland, the famous New York jazz club, were a regular family outing when Jim Grant was growing up. “He brought all sorts of non-mainstream thoughts into the household,” Jim says of his father.

The family musical tradition led Jim’s fraternal twin brother, Web, to become a professional musician. Jim originally studied the French horn at Ithaca College, but then dropped out, joined the Navy, and was a gunner’s mate on an aircraft carrier off the coast of Vietnam during the early days of that war.

When Grant returned from active duty at age 20, he landed a summer job on the bond desk at a firm called McDonnell and Co., where he developed an itch for finance — and the big money that could be made there. That was the extent of his Wall Street experience, but it led him to major in economics at Indiana State University.

After graduating, Grant went to work as a police reporter at The Baltimore Sun, where he met his future wife, Patricia Kavanagh, the paper’s fashion editor. She’s now a neurologist, following a stint as an investment banker at Lehman Brothers.

In the mid-’70s the Grants moved to New York, where Jim went to work at Barron’s. After eight years there, he took $75,000 he had amassed in his Dow Jones profit-sharing plan to start the newsletter. “It was not actually a lot, as I discovered in six months,” he recalls.

But it was an adventure. One of the first hedge fund managers the new editor met was Chanos, who says the two — along with the investment manager who introduced them — spent “five hours at this midtown restaurant talking about the world.

“I was going on and on about this guy that was not yet on people’s radar screens to the extent he would be later — a guy named Mike Milken at Drexel Burnham,” says Chanos, who was already short a number of Drexel companies, like Integrated Resources and First Executive Corp. “I was explaining to Jim this magical machine that Milken had created by this network of people who were all buying the bonds of each other. He was fascinated by it.”

Grant’s critical writing on the junk bond era would prove prescient in the late 1980s, when Milken and several in his circle were prosecuted, savings and loans institutions collapsed, and Drexel itself went down, cementing the new publication’s reputation.

“He was one of the few who saw it for what it was — that it was going to be a systemic risk,” Chanos says of Grant. “Let’s not forget how many banks and S&Ls went under, and how much criminality there was.”

Before that turn of events, however, Grant’s was a rocky endeavor — and in 1984, Grant took on the newsletter’s one and only outside investor, John Holman of bond firm Hintz and Holman, to keep the lights on.

Later, the bull market of the 1990s took another toll as Grant admonished investors to sell stocks — just as the tech bubble was inflating. “Market timing is not his strong suit,” quips Charley Grant, a Wall Street Journal reporter who started his journalistic career at Grant’s Interest Rate Observer and is one of Jim Grant’s four children.

Grant’s was too early to the tech crash. But during the following decade, the mortgage bubble and the ensuing global financial crisis happened, and the publication’s warnings led to a surge in circulation. Between 2005 and 2010, subscriptions to Grant’s more than doubled, according to those familiar with the numbers.

The rest of the financial media was facing hard times, but Grant’s was booming. At its peak it was grossing about $10 million a year, according to calculations based on estimates of its number of subscribers and the yearly cost (currently about $1,300) of a subscription, along with estimated revenues from its biannual conference, now $2,150 per ticket. (The next conference is scheduled for October 27.)

As markets plummeted in 2008, Jim Grant reassured his staff everything was fine.

“During the heat of the financial crisis, he called an all-staff briefing and told us, ‘Things might look very bleak in the outside world, but Grant’s subscribers are growing and we have a liquid and formidable balance sheet,’” Dan Gertner, the Grant’s analyst who was doing the work on mortgage securities, recalls. “Most of the liquid assets were invested in gold, and we had no liabilities.” Grant’s, not surprisingly, was carrying no debt.

What Grant didn’t tell the staff, however, was that he had recently passed on a lucrative offer to buy Grant’s Interest Rate Observer just as the financial crisis was erupting.

Grant says he has received many offers over the years and was tempted to sell many times. He eventually turned them all down. The most notable one came about 12 years ago when, he says, there was “a very flattering offer from the Financial Times.” (Grant declines to discuss the company’s financials, except to say that it’s a “very good family business.”)

“The money was head-turning, but then you got to think about life in a big organization — and there were meetings to go to. I kind of felt there’d be a cold sweat rising on the back of my neck, and I decided I would not want to go that particular direction,” Grant says.

Keeping his own counsel may be the secret to the longevity of the newsletter. In recent years, Grant’s has attempted to modernize slightly — it added daily email briefings (written by deputy editor Philip Grant, Jim’s elder son) and a weekly podcast — both of which are free of charge. But otherwise, Grant’s Interest Rate Observer remains largely the same as it was at its beginning.

Subscriptions are down from their peak, Grant allows, but not much else has changed in spite of a frenzied financial media world that turns on a Trump tweet. Grant’s remains a small operation that still churns out a crisply printed, 12-page product — with a 2,000-word macro analysis, an investment deep dive or two, and line-drawn cartoons, all delivered in a what one longtime subscriber calls Jim Grant’s “19th-century writing style.’

It’s been an enduring business model. Yet just a couple of years ago, Grant’s made a humiliating misstep — one that could have blown it all up.

Grant’s had already criticized Bridgewater’s risk-parity strategy, a portfolio of stocks and bonds levered according to volatility, which the strategy equates with risk. Jim Grant, naturally, worried about the leverage that entailed, as well as Bridgewater’s benign outlook on volatility. This view so upset the devoted readers of Grant’s at Bridgewater that, in March 2016, the hedge fund held a debate for its clients between Jim Grant and Bridgewater co-CIO Greg Jensen on the merits of the risk-parity strategy, which accounts for tens of billions of Bridgewater’s assets.

A little more than a year later, Grant’s published its now-infamous critique “The face on the Wall Street milk carton,” which suggested, among other criticisms, that there was something dodgy about the firm’s relationships with its service providers and concluded that Bridgewater was “not for the ages.”

The article created quite a stir. But as it turned out, some of the information on which Grant’s analysis was predicated proved to be faulty, which Jim Grant acknowledged in a shocking retraction made publicly on CNBC and also in the newsletter.

Even now, the error haunts him.

“We had made a terrible mistake, and I owed it to the people that we hurt to go and make it right, as right as I could,” he says. “We thought we had something we didn’t have.”

Bridgewater has long been controversial, which Grant believes may have affected his analysis. “I didn’t apply my normal skepticism to the evidence. We get all sorts of people winking and nodding and affirming that there’s something really, really wrong, and we thought we saw it in these facts and figures. And it turns out that we didn’t see it in these facts and figures, and it was horrible.”

Bridgewater did not respond to a request for comment.

The incident, however unpleasant, doesn’t appear to have harmed Grant’s business. The editor realizes he’s lucky.

“You could spend a lifetime building up a trusted franchise, and you can blow it away in one morning,” he says. “I count myself as very fortunate that we have a reservoir of goodwill such that it didn’t happen.”

His own shortcomings may even make Grant more sympathetic to others who find themselves in difficult circumstances. After Pershing Square CEO Ackman had been on the receiving end of negative press for years for his hedge fund’s losses, Grant called him and asked him to speak at last fall’s conference — a highly sought-after invitation.

“I invited him to speak the day after somebody trashed him. . . . I said I now view him as a value stock,” recalls Grant. (It was a good market call, as shares in Ackman’s publicly traded hedge fund have rebounded sharply this year.)

The invitation was all the more striking because four years earlier, Ackman, while being interviewed by Grant at an earlier conference, got into something of a tiff with his host by insinuating that Grant’s bearish views on Valeant stemmed from the fact that one of Grant’s daughters was an analyst at Chanos’s hedge fund. Ackman was famously long Valeant while Chanos was short, and Grant’s had disclosed the familial connection when it went bearish on Valeant earlier that year.

When Ackman appeared again last October, the activist hedge fund manager offered a mea culpa. “I’ve been a loyal subscriber to Grant’s, and I must have missed the issue that was on Valeant,” he joked. “Had I seen that issue, I would have saved $4 billion or something like that.”

The Valeant call was one of Grant’s best-known successes in recent years. However, Ackman has other differences with Grant, who has been bearish on Restaurant Brands, a long-standing and profitable position of Pershing Square’s. “He’s wrong,” says Ackman. But no matter. Ackman says he has been a Grant’s reader since he launched his first fund, in 1992. “It’s the only subscription I’ve kept that long,” he says, adding, “Jim is a great guy.”

Grant brushes aside the earlier incident with Ackman. “It’s easy to be big when you’re vindicated,” he notes. “On Wall Street there’s so much involved in some of these disputes that involve not just money but status and prestige. I don’t hold a grudge, and I hope others don’t hold grudges against Grant’s.”

So has Grant invited Ray Dalio to speak at the next conference to mend fences? “No, I haven’t,” says Grant, tilting his head in thought. “But that’s not a bad idea.”

Journalism hasn’t gotten any easier, either. “It’s a difficult business,” Jim Grant admits. “If you are in the business of selling basically macro musings and individual ideas and contrary thinking and value-grounded thinking to a world that is moving seemingly and inexorably to index funds, you are working with a limited face.”

That said, every other week — barring August and Christmas holidays — the editor holes up in his Brooklyn brownstone or drives to his farm in upstate New York and proceeds to write the several thousand words that make up each issue of Grant’s.

Grant remains the publication’s voice — and an intellectually imposing person to those who work for him. “At 6' 4'’, he is a towering figure. He used to stand over my desk and quite frankly intimidated me,” recalls former Grant’s analyst Gertner. “When you’re talking to Jim, you can see his eyes darting and almost literally see the wheels turning.”

Gertner, now managing director of an insurance company, estimates that 40 percent of the ideas for Grant’s stories came from readers, and 50 percent “from Jim’s head. He’s reading and thinking constantly.”

In 2006, Gertner had been at Grant’s only a few months when his boss asked him to look into the credit default swaps backing mortgage securities. “I had no clue what a CDS was. Jim had an innate sense that this was a big deal. It was 20 times as large as the bonds it was insuring,” he says.

Grant’s continued to put more of the pieces of the mortgage securities puzzle together with help from its friends in the hedge fund world. Among those whom Gertner spoke with were analysts at Elliott and Baupost, along with Pennant Capital Management’s Alan Fournier and Harch Capital Management’s Michael Lewitt (who first suggested the CDS idea to Grant).

Yet even in the heady financial crisis days, Grant’s got one thing wrong. In the spring of 2008, it was bullish on AIG only a few months before the big insurance firm had to be bailed out by the Fed.

Says Gertner, in what has become an enduring Grant motif: “Nobody’s going to be right all the time. Our job was to make people stop and think.”