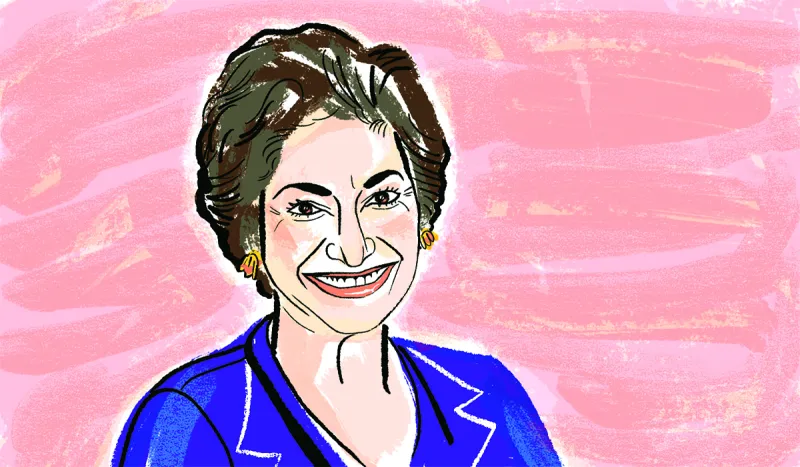

Roz Hewsenian Is Not Dying

Illustration by Sarah Tanat-Jones

The Helmsley Charitable Trust CIO — this year’s Allocators’ Choice Awards Lifetime Achievement honoree — has combined a crackling wit with decades of experience to grow the foundation’s assets to $6 billion. She’s not done yet.

Allan Emkin

Roz Hewsenian

Helmsley Charitable Trust

California

Linda Strumpf