(Jeremy Leung / II)

A year ago The New York Times reported details of decades of alleged sexual harassment by Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein. Since then nearly every industry has had its own Weinstein moment.

But not asset management.

Sure, there have been a few allegations of asset management employees acting “inappropriately toward a colleague” and engaging in “gross violations of [company] standards and values,” but these, even cumulatively, have not added up to a Weinstein-sized event.

Our industry seems to ignore the overwhelming anecdotal evidence (e.g., Lauren Bonner, who filed a gender-bias lawsuit against Point72 Asset Management, told CNN that sexual harassment is an issue that “plagues Wall Street”) and empirical data (e.g., “Almost a third of women in asset management say they have suffered sexual harassment at work, according to an FTfm poll”) that demonstrates that we are not without sin. Instead, we have adopted the default position of not directly asking managers about sexual harassment in the workplace.

For example, Pensions & Investments reports, “The Teacher Retirement System of Texas, Austin, doesn't specifically ask for information about an external manager's sexual harassment incidents, but the $151.3 billion fund's due diligence questionnaire requires prospective money managers to disclose their ethical and legal history such as any lawsuits or criminal investigations going back five years.”

This is what passes for leadership.

Asset allocators should not be mollified by managers’ newly implemented sexual harassment hotlines, escalation paths, and workplace ombudsmen. (My favorite remediation technique: “Companies are detailing what benefits top or senior executives will receive if they are terminated without cause and what benefits will be forfeited if fired for cause.”)

I also would hope they are not simply awaiting a catastrophic event. More likely, Andrew Borowiec of the Investment Management Due Diligence Association is right: "Everyone is trying to figure out what to do about sexual harassment incidents.”

That’s unfortunate because there is actually a straightforward method for tackling this problem: To find out managers’ true disposition to preventing and managing sexual harassment, asset allocators need only ask them two questions:

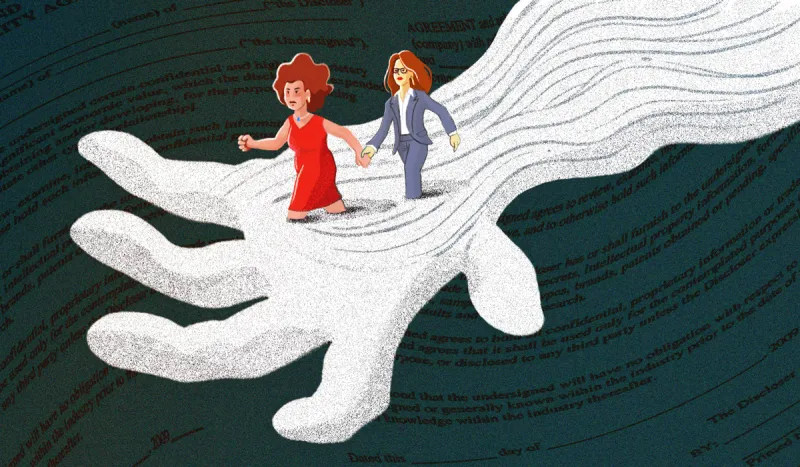

Are your employees bound by mandatory arbitration?

Are they bound by a confidentiality or nondisclosure agreement?

If they answer yes to either, ask them to explain how you — a fee-paying fiduciary — benefit from such policies.

Here’s a primer on why your sexual harassment diligence begins and ends with these two questions.

Mandatory, or binding, arbitration is a clause in an employment contract that requires grievances and conflicts be resolved through arbitration, not the courts.

Such clauses are fairly common in the U.S. The Economic Policy Institute reports that “mandatory employment arbitration has expanded to the point where it has now surpassed court litigation as the most common process through which the rights of American workers are adjudicated and enforced.”

While it is difficult to ascertain the use of forced arbitration in our industry, the same report found that 48.5 percent of finance, insurance, and real estate companies impose mandatory arbitration. And we know from a National Labor Relations Board complaint that a bellwether firm like Bridgewater Associates requires that employees “submit all [potential] claims to binding arbitration on an individual basis” and “waive any right to bring on behalf of persons other than [themselves], or to otherwise participate with other persons in: any class action, collective action, or representative action.” Likewise, Point72’s employment agreements “clearly and unmistakably” require employee grievances be settled via binding arbitration.

Despite its widespread use, employees often do not know they have agreed to mandatory arbitration because it is hidden in the contractual fine print or in an employee handbook. And even if they are aware, they typically do not have a meaningful choice to accept or reject the arbitration clause.

According to Imre Szalai, a professor at Loyola University New Orleans College of Law, mandatory arbitration is a “slanted system” because arbitration clauses “may be loaded with harsh, one-sided terms favoring an employer.”

As we see in the NLRB's Bridgewater complaint, forced arbitration can prohibit aggrieved employees from acting in concert (e.g., from filing class-action lawsuits), which, as Nantiya Ruan, a professor at the University of Denver Sturm College of Law, points out, is problematic because, “An individual cannot change the way a corporation does business.”

In their role as shareholders, asset allocators recognize that they are generally disadvantaged by mandatory arbitration. In a 2018 letter to the SEC, the Council of Institutional Investors (the self-described “voice of corporate governance”) wrote that “forced arbitration provisions . . . represent a potential threat to principles of sound corporate governance that balance the rights of shareowners against the responsibility of corporate managers to run the business.”

Separately, two of the council’s members — the California Public Employees' Retirement System and the California State Teachers' Retirement System — argued against forced shareholder arbitration, claiming in an amicus brief that “[e]viscerating the class action mechanism in securities cases would have disastrous consequences for the amici and their beneficiaries.”

The second and often related employment provision that asset allocators must be mindful of is the confidentiality or nondisclosure agreement. As with mandatory arbitration, it is difficult to determine the use of NDAs in employment agreements, but according to Kathleen Peratis, head of the sex discrimination and sexual harassment practice group at New York law firm Outten & Golden, “[I]t is absolutely expected that with every single employment settlement agreement there will be a confidentiality agreement.”

Certainly, NDAs have a place in the compact between employer and employee (e.g., protecting trade secrets, business models, and intellectual property). But NDAs have come to include civil rights issues like sexual harassment and employment discrimination.

For example, Bridgewater defines “confidential information” as “any nonpublic information . . . relating to the business or affairs of Bridgewater or its affiliates, or any existing or former officer, director, employee, or shareholder of Bridgewater."

It’s critical that an asset allocator’s investigation into a manager’s exposure to and management of workplace sexual misconduct — and, indeed, into its general workplace culture — begin by understanding the manager’s use of binding arbitration and NDAs in employment agreements. These employment clauses forcibly prohibit the asset manager and its past and current employees (and contractors) from disclosing anything about sexual transgression — or really any misconduct. (There are real, painful consequences for employees who breach such agreements. A company can seek damages and try to claw back part of a previously confidential settlement.)

This reveals the impotence of using a conventional due diligence questionnaire and other traditional means to uncover misconduct. Certainly, asset allocators can require managers to disclose their ethical and legal history, such as any lawsuits or criminal investigations. Yet if a manager and its current and former employees are bound by arbitration and NDAs, there will be no lawsuits to disclose. Moreover, the results of any arbitrations will not be disclosed and the arbitrations themselves might not even be revealed. These employment conditions effectively limit transparency into a manager’s culture, with the disclosed information being of only marginal value.

And if a manager is a bad actor, mandatory arbitration and NDAs eliminate the threat of litigation — especially class-action litigation — and the negative publicity associated with sexual harassment and other workplace allegations, thus removing an important deterrent for a company to change bad behavior and create a safe workplace.

I’m not arguing that a manager might not have bona fide reasons for using such employment clauses. But I am arguing that because of the opacity they impose, you should start your investigations by asking managers to explain how these clauses benefit you and your beneficiaries. Also, try asking them for a copy of their employment documents.

Just be prepared to sign an NDA before you get it.

If you’re an asset allocator and are interested in exploring how to include sexual harassment in your due diligence, you might want to participate in the private, peer-based working group I am curating. Contact me if you’re interested.