By Chris Wilson, CFA, Senior Client Portfolio Manager and Bryan Lazarus, CFA, Fixed Income Product Manager

Executive Summary

- Historically, the core and core plus fixed income space has been dominated by a handful of “supersized” strategies.

- Strategies that become too big either lose access to certain parts of the market, or worse, lose their ability to be selective in sectors where bottom-up underwriting of credit risk is essential to success.

- Accordingly, duration bets, which have been notoriously difficult to make successfully with any semblance of consistency, tend to become the primary driver of relative returns for supersized bond strategies.

Asset Flows Follow the Herd

Herd mentality tends to dictate manager selection in core asset classes. This is particularly true in the core and core plus bond categories where a handful of managers have historically garnered the lion’s share of investors’ assets. Since 1990, the AUM of the three largest funds in Morningstar’s Intermediate Term Bond category has represented, on average, 50% of all assets in the category. During this time, the size of the largest single fund has been more than $200bn.

The cycle goes something like this. Everybody owns Bloated Bond Fund 1.0. Bloated Bond Fund 1.0 experiences some calamity. Everybody begins to worry. Concerns intensify. Assets pour out of Bloated Bond Fund 1.0 into “The Next Great Bond Fund.”

As assets continue to pour into “The Next Great Bond Fund,” Bloated Bond Fund 2.0 is born. Of course, Bloated Bond Fund 2.0’s growing size limits its potential to continue delivering the strong historical returns that attracted investors in the first place. Rinse, repeat and the cycle continues anew. Sound familiar?

From a portfolio manager’s perspective, a strict adherence to clearly defined capacity limits is the only way to avoid this trap. From an investor’s perspective, breaking this cycle requires going against the herd—doing so with confidence requires a comprehensive view of the bond strategies currently in vogue.

Ingredients for Success in the Current Fixed Income Environment

The 2008 financial crisis dramatically altered the fixed income landscape. The Federal Reserve’s extraordinary and unprecedented monetary easing drove yields on U.S. Treasury and agency securities to historic lows—and yields have risen only modestly since the Fed began to tighten policy in 2015. As a result, low-yielding government-related debt ballooned and came to represent the majority of the flagship core bond benchmark: The Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index.

Success in this environment calls for fixed income managers to have a breadth of expertise across the securitized and corporate credit landscape, irrespective of inclusion in the aforementioned benchmark. Not surprisingly, investors have embraced managers with a track record of generating alpha in “off benchmark” sectors like non-agency RMBS, senior loans and high yield, in addition to benchmark sectors like CMBS, ABS and investment grade credit. However, as assets build up in multi-sector bond strategies, the opportunity set becomes limited and restricts these managers to focus primarily on agency and treasury securities. Old-fashioned mathematics and the laws of supply and demand can help explain why.

Too Big to Fail? A Closer Look at “Supersized” Bond Portfolios

Understanding the impact of strategy size requires a quick refresher on portfolio construction. When it comes to individual position sizes, portfolio managers walk a fine line. On the one hand, positions in individual bonds need to be sized just right to command liquidity, not too small as to be subjected to adverse bids and offers, yet not too big where you own so much of the bond that you are “the market.” On the other hand, positions need to be large enough to actually affect overall portfolio performance, yet small enough so the portfolio maintains an appropriate level of diversification.

The rigors of effectively managing these exposures is another dimension that should affect this equation. While some positions may be larger or smaller based on the manager’s conviction, positions sized at 0.25% of the overall portfolio (400 positions) is a good rule of thumb (for a properly resourced manager) to ensure exposure to individual bonds will affect performance without reducing diversification and still preserving suitable liquidity.

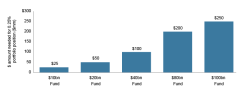

With this context in mind, Figure 1 looks at different sized strategies and shows the dollar amount needed to build a 0.25% portfolio position in an individual bond. A $100bn strategy needs to own $250m of an individual bond to achieve a 0.25% position size in its portfolio. Meanwhile, a $10bn strategy needs to own just $25m of an individual bond to achieve the same 0.25% position size in its portfolio.

Figure 1. Size Matters: Dollar Amount Needed to Build Portfolio Positions across Differently Sized Strategies

Source: Voya Investment Management. For illustrative purposes only.

As we explore in the following sections, the portfolio math in Figure 1 has serious implications for “supersized” core and core plus bond strategies seeking to generate alpha across the full fixed income spectrum.

Accessing Corporate Credit: A Day in the Life of a “Supersized” Bond Manager

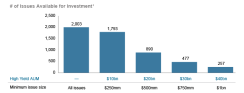

Corporate credit plays an important role in a multi-sector fixed income portfolio. In the persistently low rate environment, investments like high yield bonds and senior loans offer the potential for attractive yield. However, with the potential for higher yield comes the potential for higher risk, making security selection even more critical in these sectors. Yet, as Figure 2 highlights, effective security selection is more difficult for a supersized manager.

For example, consider a $100bn strategy seeking to implement a 20% portfolio allocation to high yield ($20bn). Assuming a 0.25% holding size, a $100bn strategy can only access 851 of the 2,183 available high yield issues (Figure 2). Of course, a manager could decide to decrease the holding size to accommodate more of the high yield universe. But remember, doing so would severely limit the impact the holding will have on the portfolio’s performance and, depending on the depth of the platform, dilute the efficacy of a manager’s approach to tracking portfolio risk.

Figure 2. The High Yield Opportunity Set Dwindles as Strategy Size Increases

As of 5/23/2018.

Source: Barclays, Voya Investment Management. 1To achieve a 0.25% position size with maximum holding of 10% of outstanding issue.

This dynamic creates two options for managers of supersized strategies seeking high yield:

- Option 1: Build positions in high yield bonds with a significantly limited opportunity set, compromising their ability to be selective

- Option 2: Maintain a full opportunity set with position sizes that are not large enough to materially affect the performance of the broader portfolio

Accessing Securitized Credit: A Day in the Life of a “Supersized” Bond Manager

The ability for a supersized manager to access attractive opportunities in the securitized credit market can be even more limited. Securitized credit offers a diversified menu of exposures, from the residential housing market, U.S. consumer, the corporate credit cycle and commercial real estate market. In addition, securitized investments offer a spectrum of structural protections, yield profiles and coupon structures. The weighted average life of securitized credit investments also varies within and across subsectors, providing additional diversification benefits in a broader portfolio. Thus, not only can securitized credit provide diversification from other asset classes, a broad securitized allocation benefits from strong diversification benefits within the individual securitized sub-sectors.

However, as the following examples demonstrate, supersized managers simply cannot access the full scope of securitized credit’s potential diversification benefits.

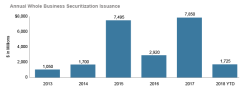

ABS: Whole business securitizations

Securitizations of whole business cash flows re-emerged as a source of ABS supply, offering attractive yields with investment grade ratings and unique exposures to iconic, global brands. However, supply of whole business ABS, while resurgent, is limited—only $7.5bn was issued in 2017. This level of supply would be simply too small for a supersized manager.

Source: JP Morgan

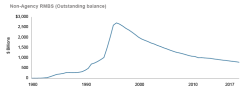

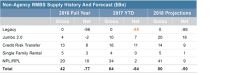

Non-agency RMBS

As the legacy portion of the non-agency RMBS market shrinks, maintaining allocations to this attractive and diversifying source of risk will likely be a challenge for supersized strategies. In addition, as new forms of mortgage credit become available, properly identifying sound risk-reward combinations requires - among other attributes - a degree of selectivity.

As of 12/31/17

Source: JPMorgan

Similar to corporate credit, supersized managers seeking securitized exposure are more likely to access the market through the larger, more liquid agency RMBS segment. However, due to the nature of the agency guaranty in agency RMBS, there is little to no exposure to the credit component. As a result, interest-rate risk is the dominant driver of return for agency-backed residential mortgages, which matches the primary risk of Treasurys.

What’s Left for a Supersized Manager?

As demonstrated in the previous sections, the opportunity set for core and core plus bond strategies becomes more limited as a strategy grows in size. Strategies that become too big either lose access to certain parts of the market, or worse, lose their ability to be selective in sectors where bottom-up underwriting of credit risk is essential to success.

As a result, supersized multi-sector bond portfolios are primarily built with positions in lower yielding U.S. Treasury and agency debt and investment grade credit. Accordingly, duration bets, which have been notoriously difficult to make successfully with any semblance of consistency, tend to become the primary driver of relative returns for supersized bond strategies.

Of course, managers of supersized bond portfolios could access securitized and corporate credit sectors through derivative markets.

Yet as we witnessed in the 2008 financial crisis, derivative exposures are blunt instruments and do not always reflect the precision afforded by the performance of a portfolio of specifically selected underlying bonds. A significant reliance on derivatives also introduces new risks into a portfolio and adds a layer of operational complexity to portfolio management.

Break the Cycle

Investors in supersized strategies should consider charting a new path that goes against the herd. Given ongoing market dynamics, the nefarious cycle of the Bloated Bond Fund is likely to continue. Investors cannot know when or how this cycle will end—but there is no reason they need to stay with the pack to find out.

A more moderately sized bond strategy can access a much broader opportunity set and leverage a full breadth of alpha sources, which in turn can provide investors with more consistent outperformance through a changing market environment.

Disclosures

This commentary has been prepared by Voya Investment Management for informational purposes. Nothing contained herein should be construed as (i) an offer to sell or solicitation of an offer to buy any security or (ii) a recommendation as to the advisability of investing in, purchasing or selling any security. Any opinions expressed herein reflect our judgment and are subject to change. Certain of the statements contained herein are statements of future expectations and other forward-looking statements that are based on management’s current views and assumptions and involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties that could cause actual results, performance or events to differ materially from those expressed or implied in such statements. Actual results, performance or events may differ materially from those in such statements due to, without limitation, (1) general economic conditions, (2) performance of financial markets, (3) interest rate levels, (4) increasing levels of loan defaults, (5) changes in laws and regulations, and (6) changes in the policies of governments and/or regulatory authorities.

Voya Investment Management Co. LLC (“Voya”) is exempt from the requirement to hold an Australian financial services license under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (“Act”) in respect of the financial services it provides in Australia. Voya is regulated by the SEC under U.S. laws, which differ from Australian laws.

This document or communication is being provided to you on the basis of your representation that you are a wholesale client (within the meaning of section 761G of the Act), and must not be provided to any other person without the written consent of Voya, which may be withheld in its absolute discretion.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results.