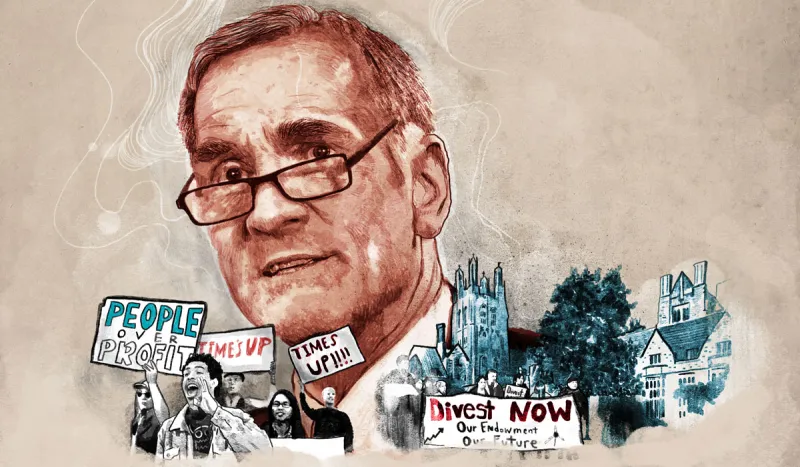

David Swensen Wrote an Angry Email. Then He Pressed Send.

Illustrations by Peter Strain

In an exclusive interview, the Yale endowment legend explains how, and why, he finally lost his cool.

Puerto Rico

David Swensen

Yale

Yale Daily News

Yale Investments Office