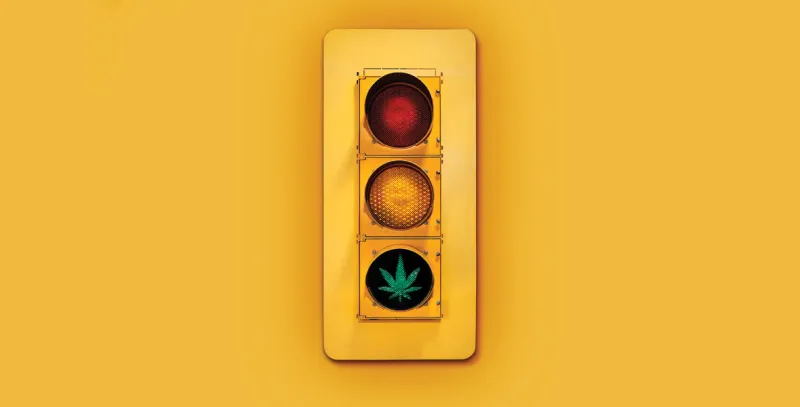

Illustrations by Justin Poulsen.

Steve DeAngelo has two gray pigtails, a felony drug conviction, and $150 million invested on his ArcView platform.

“What I see happening now is the fruition of all the hippie pioneers’ most cherished dreams,” says DeAngelo. He’s a leader in the tie-dyed culture that nurtured cannabis under prohibition and, soon, out of it.

Semilegal weed has sparked a Wall Street land grab. DeAngelo uniquely has a foot in each world, and arms open to the inrushing suits. Hippie culture can not only survive financialization, he argues, but needs it to help spread the plant magic worldwide. Since the early days, “we felt that if more people consumed cannabis, the world would become more peaceful, more sustainable, more just, and a more pleasant and fun place to live in.”

That mission takes money, he stresses. “There aren’t enough hippies in northern California — or the whole world! — to take this plant to everybody on the planet who needs it. The only way cannabis will make it into the medicine chest of every family around the world is if you engage with the global business infrastructure,” DeAngelo argues from the Oakland, California, Marriott hotel. Not far away is his 200,000-patient medical cannabis dispensary, Harborside Health Center. During the interview, DeAngelo speaks lovingly of both the outsiders who nurtured the plant as criminals and the new money that hopes to bankroll it legally. The hippie outlaws have become the experts. They’re critical, in DeAngelo’s view, to financiers’ getting legal cannabis into the hands of people around the world.

This circuitous activist career started when DeAngelo dropped out of school at 16, joined the Yippies, and became a lead organizer of the annual Fourth of July Smoke-In in front of the White House. Years later, in 1998, he would play a key role in the city of Washington, D.C.’s vote to legalize medical marijuana. (It took 15 more years before a patient could actually buy the therapeutic drug aboveboard.) DeAngelo’s also been a weed dealer, a nightclub manager, and a record producer, and founded Washington D.C.'s Nuthouse, an ’80s-era refuge for cannabis activists.

Oakland’s Marriott was hosting the New West Summit, a cannabis conference that attracted potential investors, newly minted app entrepreneurs, cryptocurrency payment system operators, and longtime cannabis activists and business owners. Instead of finding the usual exhibit hall swag like golf shirts and coffee cups stamped with corporate logos, vendors offered hemp products for nervous dogs, pre-filled vape pens stamped with the desired effect (Passion and Arousal were crowd-pleasers), and samples of new brands like Can of Bliss: Premium Cannabis in a Can.

DeAngelo co-founded the first cannabis angel investment network, ArcView Group Troy Dayton, in 2010 to match investors — dentists and doctors at first, now family offices and the Silicon Valley rich — with weed entrepreneurs. One of the most respected cannabis testing labs, the Steep Hill Labs, also belongs to his burgeoning empire. Part pot evangelist, part capitalist, DeAngelo asks outsiders to partner with people who have worked illegally in the trade for decades. They have deep agricultural and processing knowledge and understand how the drug works in food, alcohol, and the body. He thinks weed’s charms will eventually win over even the most mercenary capitalists. “After a year or two, they come to me, kind of a confession, and say, ‘Steve, I’ll be honest with you, it was just about the money. But then I started hearing these amazing stories.’ And then they tell me a few of these amazing stories. ‘I understand now why you’re so moved by this. I’m with you.’”

It is about the money, though. Even though California has been a quasi-recreational state for years, as almost anybody can get a doctor’s prescription for cannabis, the state is making it legal for people to partake just for the fun of it beginning January 1. California, which is closely watched because it now represents about 40 percent of the U.S. market for cannabis products, first legalized the medicinal use of marijuana in 1996 after years of lobbying by AIDS activists. Next year, shocking even some longtime advocates, marijuana will be fully legal in 17 states, with 12 more allowing people to use it as medicine.

Matt Karnes, a former equity analyst who started cannabis research firm GreenWave Advisors four years ago, expects U.S. legal retail weed sales to reach $30 billion by 2021, up from $6.5 billion in 2016. In just three years an astonishing 29 states are expected to have fully legal markets, and all 50, as well as Washington, D.C., will allow at least medicinal use, he says. In comparison, wine sales in the U.S. are $29 billion. “The smoke is out of the bong,” says Karnes, who says he loves the excitement of being off Wall Street and part of the Green Rush. He estimates that 30 million people in the U.S. use cannabis recreationally and by 2021 will spend $1,500 a year on average. Over the same period a further 26 million possible medical users will spend a projected $3,200 a year.

Given the momentum behind the legalization of marijuana in the U.S., the most powerful investors in the world are seriously evaluating how they can profit from an industry that governments around the world once spent billions trying to eradicate. Cannabis-focused private equity firms include Northern Swan Holdings, started by former KKR and Och-Ziff Capital Management executives; Tuatara Capital; and Privateer Holdings, which raised money from Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund in 2015. They’re primarily targeting ultrahigh-net-worth investors, family offices, and other sophisticated investors flexible and brave enough to put money into gray markets. Meanwhile, traditional mutual funds, private equity firms, institutional asset managers, pension funds, and endowments that have had nothing to do with cannabis are sizing up the opportunities from a safe distance. Most don’t care much about the history of the plant. They’re doing due diligence, attending conferences, and getting to know their way around an industry whose foundation was — and still is, in most cases — illegal. Fidelity Management & Research Co., among others, has ventured into hot companies like PAX Labs, which makes perfectly legal vaporizers for tobacco and cannabis.

Institutional investors can also put money into companies listed on the Australian Securities Exchange and perhaps soon on Börse Berlin, and into all kinds of ancillary businesses, including agricultural technology, software, and cultivation equipment. The stock of Scott’s Miracle-Gro, a suburban garden shed staple, has been on a tear since the company expanded into hydroponics and other products attractive to weed growers.

“We’ve had more conversations with larger institutional investors in the last six months than ever before,” says Brendan Kennedy, CEO of Privateer, which focuses on consumer brands in cannabis. Kennedy first heard of the industry in 2010 while chief operations officer of tech start-up SVB Analytics, when a client from a medical cannabis company came into the firm’s offices. “When they left, I went to the computer, which had every business database at the time, and I typed in every word I could think of for cannabis. Nothing came up!” he says. “If you can’t find information, that’s an opportunity.” Kennedy left SVB, put together a team, and spent a year visiting dispensaries, cultivators, retailers, lawyers, politicians, and others around the world, including in the hills of Oregon and northern California, British Columbia, and Israel. Like many early investors in the markets, he and his co-founders started Privateer to help usher in an end to prohibition and its resulting social problems — and make killer investments along the way.

Legal recreational use in California and Canada is slated to begin next year, which Kennedy thinks contributed to the recent spike in institutional interest. “Sometimes I point out two of the world’s top ten economies are legalizing cannabis for adult use. Canada will be a model for other countries,” he notes. From California — the global superpower in cultural exports — Kennedy expects movies and television programs that show adults smoking pot.

Finance people see vast opportunity in former black markets: They are messy, opaque, cash-based, often without any records to speak of, and have plenty of holes to fill. It’s the stuff Wall Street careers are made of. When an investor successfully cleans up a mess, it is called alpha or excess returns. After the pot is smoked, the financial industry will take a business, document its process, build better systems, bring in professional managers, squeeze out efficiencies, and do a few mergers and acquisitions. Already in 2017 public companies have raised $1.4 billion in 177 equity and debt deals, compared with $543 million raised in 2016, according to Viridian Capital Advisors. Private companies have done an additional 110 deals, raising $494 million, compared with $193 million last year. This year there have been 118 M&A transactions, compared with 58 in 2016, says Viridian.

Robert Hunt, principal of ConsultCanna, a boutique consulting firm that provides market intelligence on the industry, sees change coming to the California cannabis market, and it will presage what happens nationally. He predicts massive M&A opportunity as organizations try, and fail, to go legit. Over the next two to three years, one cannabis retailer, for example, may buy up several smaller companies and build a 60-store chain. “This will obliterate the cannabis market that exists today and create a brand new one run by adults,” says Hunt.

With all the promise of growth, though, cannabis businesses are still hamstrung when it comes to services that most businesses take for granted, such as bank accounts, lines of credit, mortgages, and working capital. With the drug still regulated under a patchwork of state laws, businesses can’t easily get banking services. “If a grower wants to buy a warehouse, they do cash deals,” says Scott Greiper, who founded Viridian after 20 years on Wall Street covering global security and IT companies.

“Three years ago, investors wanted to play in cannabis, but with the protection of being a lender rather than an investor,” Greiper says. Since the end of 2015, as more states have legalized the plant, things have changed. Now deals offer more common and preferred stock and less debt. “With 70 percent of the citizenry living in a legal state, it makes sense that investors would be more comfortable taking on more risk these days.”

Due diligence is a perk, not a chore, of the cannabis finance game. About 50 investors — some Silicon Valley veterans, others having made money in cryptocurrencies or retired from Wall Street — mingled last month at the Minna Art Gallery in San Francisco’s SOMA neighborhood. Attendees yelled into each other’s ears over the music, waiting for dishes drizzled with pot-laden sauces from a well-known “infusion” chef. The party reeked. But not of the thick fog variety many baby boomers associate with suburban rec rooms. Mistier, but inescapable. A jewelry maker with plans for a line of vaporizers specifically for women says many people now prefer gadgets that heat, rather than burn, the drug. They can be rather discreet.

If all that sounds sanitized, it is. Gregg Schreiber helped found Green Table to connect investors with entrepreneurs at events like the Minna Gallery’s, and tries to tidy potential deals before his investors get a look at them.

Whereas DeAngelo speaks of peace, love, and money, Schreiber just sticks to money. He worked at Lehman Brothers and then Bear Stearns in institutional fixed-income sales for 14 years, until 2007 when the firm fell apart in the run-up to the financial crisis. Schreiber tried to make a living as an interest rate trader in a low-rate world with no volatility, then moved to Los Angeles. A wealthy friend, whom he won’t name, asked him to find him worthwhile deals in cannabis.

“People here knew I had connections to Wall Street money, and three months later I found myself with 100 decks on my desk,” Schreiber says. He is a ball of New York energy squirming in a chair at a bar in the Oakland Marriott, watching a Yankees game and talking to a reporter. “Most deals in cannabis are terrible. I wasted a year and a half with these companies. I didn’t know what I was doing,” he explains. But Schreiber soon started figuring out who to stay away from and who to trust. He calls Green Table a capital-raising function masked by a dinner. He now represents investors who are willing to write checks of $500,000 up to $3 million, but still won’t put in front of them 90 percent of the companies he looks at.

Schreiber sees a definite culture clash between newer entrants like himself and the old guard of the cannabis business, which feels a little like a Grateful Dead concert. “We come on strong — sometimes we’re offensive or too much. But I’m a businessman. A lot of people from the cannabis industry think it’s about the common good, that kind of mentality.” Not, in other words, Wall Street. “When I was at Bear,” he says, “I always protected my biggest clients like they were my first-born.” Even as a newcomer, Schreiber is glad he’s early. “I’m involved now so that when people want to come in, they’ll come to me.”

Emily Paxhia — she and her brother co-founded Poseidon Asset Management in 2013 to focus exclusively on cannabis companies — says the only diligence worth doing is hands-on and in person. “If you don’t see, you don’t know,” she insists. “It’s like the subprime crisis. Unless you went to people’s houses and saw for yourself that homeowners weren’t paying, you didn’t know what was happening.” Still, Paxhia says that people entering the business now have it easy. “All the hard work we’ve done. They have data rooms, due diligence lists that companies are used to providing, there is research,” she explains. “We’re right at the final push.”

Poseidon has raised two funds, invested in 40 companies, made nine exits, and marked two holdings to zero. Unlike some firms, Poseidon — which invests in agricultural technology, compliance technology, genetics, lab testing, the whole ganja gamut — will touch the plant. Handling the greenery remains a federal crime. But the price of cannabis has fallen with rolling legalization, turning the plant into a commodity. One of Poseidon’s portfolio companies — Flow Kana — wants to build the infrastructure.

Michael Steinmetz, founder and “chief servant officer” of Flow Kana, is constructing a one-stop worksite for independent pot farmers to test, dry, cure, process, manufacture, and distribute cannabis. Steinmetz built and sold a successful food distribution company in Venezuela before founding Flow Kana. The company’s brand is all about sun-grown organic cannabis from independent owners and family purveyors. Cereals and packaged breads proved decades ago that branding products, particularly in new categories, can lock in customers (“That’s my strain”) or command higher prices for, say, commodity weed in a beautiful jar. This kind of branding has investors salivating at the opening up of cannabis: It’s like the early 20th century, and everyone wants to back, or become, the Kellogg brothers and Charles W. Post.

During prohibition hippies fled the cities of California and went north to grow marijuana — first for their own use, later for sale. Fields dot the hills of Mendocino, Humboldt, and Trinity counties. This Emerald Triangle microclimate turned out to be perfect for growing cannabis. The region now supplies 85 percent of the nation’s consumption. But with dropping prices, open markets, greater competition, and — gasp — regulation, farmers have to bring down the cost of production. Furthermore, the wildfires that have raged in Sonoma and Mendocino counties, among other regions, either incinerated cannabis farms or tainted crops with toxic smoke and ash. The vast majority of farmers are still uninsured.

Flow Kana began by bringing multiple farmers into the white market, delivering their cannabis products under the Flow Kana brand directly to patients in 2015. “This was organic medication grown by these small farmers,” says Steinmetz, who sounds as though he could be hawking artisanal cheese as much as pot. In the black-market days, he explains, “you had no idea what you were getting. You just wanted the dealer out of your house. I call it moonshine cannabis. It was all unbranded.”

Brands are Business 101. Privateer focuses exclusively on consumer brands. “We’re investing in the Diageo of cannabis, the P&G of cannabis,” says Privateer’s Kennedy. In 2014, Privateer formed a partnership with the family of Bob Marley, the Jamaican singer who is virtually synonymous with weed, to launch Marley Natural, which now includes body care and smoking accessories.

Steinmetz’s Flow Kana grew fast, but the company couldn’t source the product fast enough, with employees having to travel through the Emerald Triangle, an area the size of Ireland, to pick up farmers’ goods. Flow Kana needed a central location. Earlier this year the company bought the old Fetzer family winery, which had once been the third-largest in the U.S., and cannabis processing facilities are under construction. Farmers will drop off fresh harvests, and Flow Kana will dry, cure, and trim the plants into finished products. This process represents about 60 percent of farmers’ cost of production, Flow Kana estimates.

Flourishing commercialism makes it easy to forget that the cannabis plant remains illegal under federal law. For Steinmetz “it reminds me of my days in Venezuela operating in a third-world environment.”

Boos rang out at the New West Summit at the mention of Attorney General Jeff Sessions. He has vowed to block any attempts to legalize cannabis. Without federal legalization, laws and regulations enacted by the states are in contravention. Many believe that is a temporary limbo. “We’re as far away from legalization as the Trump administration lasts,” says Kyle Detwiler, who spent ten years at KKR and Blackstone before co-founding Northern Swan. Northern Swan, which doesn’t mention anything about cannabis on its website, is a holding company — rather than a fund with a fixed life — that can hang on to investments for the long term. That way the firm doesn’t have to try to predict when the U.S. will legalize the drug.

“Once legalization happens, everything would triple in value, and we don’t want to be forced to sell before that happens,” Detwiler notes.

In Oakland, Steve DeAngelo is in a bland hotel ballroom teeing up a small crowd for a speech. He begins with the Summer of Love 50 years ago and finishes with a rowdy call to “come out of the cannabis closet!” Applause. “Show the world what is evident and obvious: that the people who are building the cannabis industry and consuming cannabis are responsible people who are engaged, creative, and productive.” DeAngelo doesn’t want these businesses to be just another alpha-generating sector for investors and Wall Street. “The industry will become whatever the people in the room, and rooms like this all over the state, want.” For the powerful, learning cohort of financiers, what they want is, always, money. DeAngelo knows. He finds himself a founding father of a movement that’s leaving his people behind.

“Today many of those pioneers are being squeezed by the influx of capital and professionalism that is coming into this industry,” he urgently tells the conference attendees. “Those of you who are new to the industry, make some room. Do what you can to learn from them. Bring them into your businesses!” The mogul of marijuana is in the final rounds of a 40-year fight with the Feds, and winning. Fortunes, his among them, will be lost or multiplied on the outcome. It’s all very Wall Street.

Photo credits: (Image 1: Photograph of Steve DeAngelo, Jamie Soja / Courtesy Harborside; Image 2: Cannabis World Congress & Business Expo., Dania Maxwell/Bloomberg; Image 3: A young enthusiast tokes up at a marijuana festival in Canada, David Kawai/Bloomberg; Image 4: Authorities raid a marijuana farm in Kentucky, Luke Sharrett/Bloomberg).