When it comes to fossil fuels, California Insurance Commissioner Dave Jones wants his industry to clean up its act. In January, Jones requested that insurers licensed to sell in California voluntarily divest from thermal coal. He also announced that as of April those companies — which collectively manage investments worth $7.5 trillion — must disclose their oil and gas holdings.

This move comes as coal’s fate as an attractive investment appears to be all but sealed, raising the question of whether oil and gas are next. “Policy changes and indicators in the markets themselves led me to conclude that coal in particular poses a financial risk to insurance companies, and that oil and gas pose enough of a risk to warrant new requirements with regard to financial disclosure,” Jones says.

He cites carbon emissions standards in various U.S. states, California’s cap-and-trade system and December’s 21st Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in Paris, where world leaders agreed to reduce emissions and keep the global average temperature rise below 2 degrees Celsius.

In a February research note, Goldman Sachs Group analysts called the decline of the thermal coal industry “irreversible,” thanks to an ongoing plunge in demand for the most carbon-intensive fossil fuel. The analysts lowered their long-term price forecast for Australian Newcastle coal, which traded at $51 per metric ton as of February, to $42.50, down 15 percent from their previous estimate of $50 last September. Meanwhile, the Market Vectors Coal ETF keeps sinking: In early March it was trading in the $7.25 range, having plummeted almost 90 percent since June 2008.

With petroleum prices also tanking — Brent crude was about $36 a barrel in early March, versus $112 in June 2014 — some investors are treating the slump as a buying opportunity. Jodie Gunzberg, New York–based global head of commodities and real assets at S&P Dow Jones Indices, says many of her investor clients have allocated to oil majors in expectation of a rebound.

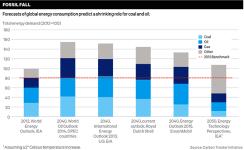

But other investors worry that oil and gas face the same threat as coal: a permanent decline in global demand, spelling ruin for companies that don’t reinvent their business models.

“Investors are being asked to make a judgment call,” says Mark Campanale, founder and executive director of the Carbon Tracker Initiative, a London-based nonprofit that seeks to mobilize capital markets to fight climate change. “Do they back what governments are saying, that we’re going to have to put in place a regime to control emissions and get the use of fossil fuels down by 30 percent, or do they believe the companies, who want to increase the supply by 20 to 30 percent? That is the fundamental dilemma that investors face.”

Some asset owners are trying to confront that dilemma by taking both extremes into account — and pressuring the oil and gas industry to prepare for a world that governments claim will be less dependent on carbon. The $180 billion New York State Common Retirement Fund and the £6.7 billion ($9.35 billion) investment fund overseen by the Church of England have opted for shareholder engagement. Both players hope they can help to persuade the oil and gas majors in their portfolios to adapt to a lower-carbon world by doing things like investing more in renewable energy.

Over the past five years, the corporate governance program overseen by New York State Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli has filed 41 shareholder proposals calling on portfolio companies — most of them in the energy sector — to assess their climate change risks and their strategies for confronting those risks. As of last September, New York State Common had 2.12 percent of its total holdings in members of the Carbon Underground 200, an annual ranking of the top 100 public coal companies and the top 100 public oil and gas companies by potential carbon emissions from their reported reserves.

In response to shareholder pressure from the Church of England and others, BP and Royal Dutch Shell agreed to publicly describe how government clampdowns on emissions will affect them. But engagement can face roadblocks: After New York State Common and the Church of England filed a resolution in December asking Exxon Mobil Corp. to publish annual assessments of the long-term impact of climate change policies on its business, the U.S. oil giant requested that the Securities and Exchange Commission throw out the proposal, calling it “vague and misleading.” As of early March a decision from the SEC was still pending.

Patrick Doherty, director of corporate governance at the New York State Comptroller’s office, hopes that such pushback will fade. “Companies see the writing on the wall; they see that governments are beginning to take this very seriously indeed,” Doherty says, pointing to businesses in New York State Common’s portfolio: “A number of them are beginning to take steps that they had been resisting for some years.”