Rob Mazzoni, Sector Lead, Technology

Mark Watson, Investment Specialist

It has been written that software will “eat the world.” Thirteen years on from that provocative forecast and with an estimated market size of over US$700 billion in 2024, that thesis appears to be on track.

Now, with AI sitting down at the table, the menu may be rapidly expanding and even software itself may be at risk.

In this paper, we explore what software has achieved to date and consider what it might be able to teach us about the future of AI. We also dive into the role venture capital is playing in AI disruption and what prior innovations might indicate about potential winners and losers along the way.

How hungry has software been thus far?

There are countless examples of disruptive software to look at, but just consider that the world’s largest car company by a long shot is Tesla. It didn’t get there by selling the most cars or achieving more profitable margins. In our view, Tesla’s massive market cap1 is fueled by its preeminent software capabilities. Its cars are powered by over-the-air software updates, with full self-driving capabilities (even if not yet fully autonomous) using advanced software.

At the same time, mom-and-pop restaurants are harnessing Square’s and Toast’s software, key entertainment categories are built by or delivered by software, and even credit underwriting has been disrupted by the technology.

Businesses of seemingly every stripe use SaaS software to run countless functions. We’re leaving out myriad examples, but the trend suggest software has devoured huge swathes of the economy. The rapid ascent of AI raises two key questions amid this disruption: How can AI help software penetrate previously untapped sectors and how might the new technology affect traditional software companies (and their existing use cases)?

AI disruption: What’s still on the menu?

With the widespread applications noted above, it might be surprising that more than 90% of the economy is largely untouched by software. Education, health care, the legal industry, and consulting are just a few substantial sectors with significant under penetration to date. Notably, nearly 85% of US employment is in services-based work, which technology has thus far had a more challenging time automating.

Despite this apparent buffet of growth potential, very few public software companies are forecast to grow more than 30% in the next 12 months. Why is that? In part, this may be due to persistent unwinding of pandemic-fueled overspending and a greater focus on only best-in-class, highest ROI platforms.

But critically, AI may also be taking the wind out of the sails of many segments of traditional software.

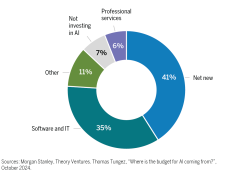

Indeed, corporate IT budgets are being reallocated to AI solutions with an estimated one-third of AI funding in 2024 coming from existing software budgets (Figure 1). In fact, more than US$100 billion has been spent on AI in the past 18 months.

Figure 1: AI budget sources in 2024

Who’s winning the AI innovation race today?

So far, AI is following the classic “picks and shovels” of innovation metaphor.2 Today, it’s primarily the enabling technologies that have billions of dollars in revenues in AI land. These include companies like NVIDIA (which supplies GPUs purpose-built for AI training), foundation model builder OpenAI, and the big three of Amazon, Google, and Microsoft (which supply critical cloud computing capabilities). In the case of foundation models, gross margins continue to improve as cost per token declines, but appetite for capital (and therefore, burn) is relentless to remain at the forefront of model performance. The large profits of the NVIDIA and the cloud providers are currently at the expense of model builders and the AI applications they support, all of which seem willing to pay whatever price to keep up.

In contrast to the enablers, the market is relatively nascent in developing and adopting AI applications, including those to fulfill the lofty promise of services-based work automation. We have spent considerable time with teams building AI-powered platforms for customer support, software development, sales automation, content creation and editing, and legal work, among other sectors. Many of these startups are growing quickly (100s of percent growth rates) and reaching meaningful scale (some surpassing US$100 million revenues) in short order. For AI apps as a category, however, revenue has not yet made much of a dent in the sizable capital expenditures for infrastructure and model development, leaving ROI an open question. How long can this dynamic hold?

Encouragingly, the incumbent public technology companies are leveraging GPUs and generative AI to optimize ad performance and drive higher conversion. Big tech may bridge the gap by generating positive returns on GPU consumption via their existing businesses, giving time for startup-driven AI applications to take hold (as long as the capital keeps coming).

AI venture capital

Where do the billions of dollars of “burn” described above come from if you’re not one of the large and profitable big tech players? As in any innovation wave — think back to software, the internet, mobile, and crypto — venture capital (VC) is funding these new AI startups. Critically, many of the eminent venture firms of the past decade are those who made early investments in the big tech and software leaders of today. It’s easy to imagine that the premier VC names of the future may be those that back the right horses in this great AI race.

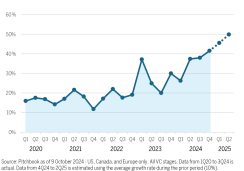

With that potential prize at stake, it’s no surprise that, at current growth rates, in 2025, roughly half of every VC dollar will be invested in AI companies (Figure 2). This could create a virtuous cycle where opportunity fuels startup activity, which drives further investment, which, in turn, powers even more startup activity. However, this cycle can become vicious if the market opportunity is insufficiently large or if copycat startups compete away price and value. Crucially, model performance has so far continued to improve so we remain highly optimistic that this is an enduring market opportunity. In our view, AI-powered technology will augment (and in some cases, entirely automate) more and more services-based work.

Figure 2: AI as a % of venture investments

AI for software development

Amid that disruption, the job for venture investors is to pick both the sectors and companies with the greatest potential to survive and thrive. For example, we believe AI for software development presents a significant opportunity, potentially enhancing developers’ productivity by automating code writing and mundane tasks. This could lead to an increase in both the quantity and quality of software (while also displacing some high-priced software developers). However, with more than 10 startups and a major industry player in the field, identifying the potential winner is essential. This is particularly true given that this space has more than US$10 billion in private market valuations despite no players generating more than US$50 million in run rate revenues (to our knowledge).

Within many categories of AI, from coding to language translation to content creation, investors also consider the possibility that entire sectors could be subsumed by the leading model builders, as those models keep improving and becoming more expert across domains. For example, could OpenAI’s models become so good as they approach (or achieve) Artificial General Intelligence that OpenAI is the best AI model for software development, rather than a vertical application company? We currently think tremendous value will accrue to specialized companies that do jobs exceptionally well, but it’s an important question to which we keep coming back.

Bottom line: The outlook for AI startups

The pace of change, model improvement, and overall innovation in AI make the startup winners hard to predict. The same dynamics make us optimistic that as in prior periods of dislocation, huge AI-native companies are being built. There are clear winners in this first wave of growth, but, in our view, it’s just the beginning, and it could take time for applications to take hold. Just look back to VC industry returns for 1999 – 2002, as the foundations of the internet and later mobile waves were being built. Hint: Those vintages barely broke even in aggregate, yet infrastructure investments during this period paved the path for huge returns from applications in the ensuing decades.

Given the creative, human-like nature of AI, far more of the economy is now in technology’s crosshairs, which should bode well for productivity as leaders emerge. Existing software companies that fail to deliver high ROI would have been disrupted regardless, in our view, but AI is a likely accelerant. Moreover, AI may quickly redefine what we mean by high ROI, increasingly adding software use cases to the menu.

Learn more about Private Investing at Wellington

1Tesla’s market cap is US$750 billion at the time of this writing.

2 This metaphor refers to the trend of enabling technologies being the first to benefit from an innovation. It is a reference to the success of companies selling equipment in the California Gold Rush.