Most investors would agree that transitioning to a net zero economy makes financial sense over the long run. The most reliable climate models show that the future gains of containing global warming far outweigh the investment required to reduce carbon emissions to safe levels.

Research conducted by Oxford University for Pictet Asset Management (Pictet AM) in 2020 suggests that the world could lose up to half of its potential economic output by the end of this century if effective measures to mitigate climate change are not put in place. A loss of such magnitude would far exceed the costs associated with developing a sustainable green economy.

Yet even if these long-run assumptions aren’t in dispute, there is a serpent lurking within the net zero paradise. The energy transition could cause considerable – if not severe – disruption over the medium term.

A study undertaken on behalf of Pictet AM by the Institute of International Finance (IIF) identifies three specific transition risks investors will need to attend to over the next five to seven years.

Chief among them is a surge in government debt.

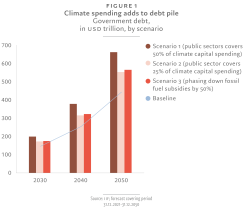

Assuming governments continue to fund half of all the climate spending required globally, net zero investment alone could potentially add over USD50 trillion to governments’ debt piles by 2030 and over USD215 trillion by 2050. This would account for over one-third of the projected increase in government debt through 2050 (see Fig 1).

Growing debt burdens are likely to have a negative effect on the credit profiles of the many countries that are already financially stretched in the wake of the Covid pandemic.

The second transition risk confronting investors is economic disruption. The laws and regulations designed to penalise carbon emitters – such as carbon taxes and the EU’s border adjustment tax – will inevitably add to the cost of doing business. Currently carbon taxes are applied to less than 25 per cent of human carbon emissions; extending their reach – and raising the amount of tax from the current rate of less than USD10 per tonne on average to well above USD150 – would likely increase input costs for almost every industry. While companies may absorb some of that transition expense, much of it will inevitably be passed onto households in the form of higher prices for goods and services, the report says. This could weigh on consumption and, ultimately, GDP growth. The IIF’s calculations show that real GDP could be some 1 to 4 per cent lower by 2030 under this scenario than would otherwise be the case.

Economic disruption might also come in the form of volatile inflation. According to the IIF, even if lower real GDP growth could act as a brake on inflation, supply bottlenecks for commodities essential to the energy transition could re-ignite prices pressures.

Estimates from the International Energy Agency (IEA) show that switching to renewable energy will require a dramatic increase in mining activity. By 2040, the IEA estimates that the world will need a 41-fold increase in nickel production, a 28-fold rise in copper and graphite supply and a 21-fold increase in cobalt availability. Yet on current trends, the mining industry will not reach these production volumes, implying supply shortages and higher prices for transition-critical minerals.

The IEA warns that copper demand could outstrip supply as soon as 2025, and it is a similar picture for many other energy transition materials. Further complicating matters is the introduction of new environmental and labour regulations designed to improve the mining industry’s environmental and worker safety standards. These inadvertently extend the timeline for new mines to become operational. So if metals shortages become a persistent problem, the resulting surge in commodities prices could lead to a significant period of greenflation.

A third side-effect of the net zero transition is financial market instability. Capital projects, particularly those directed in part by governments and state institutions, are always vulnerable to mismanagement. And the greater the amounts being invested, the greater the potential waste and damage.

This can make life especially difficult for investors. To reduce carbon intensity, they must be prepared to either channel capital to nascent technology or direct investment to companies whose track record on carbon reduction is poor in the expectation that the situation improves. Or both.

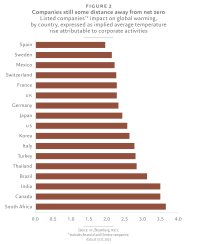

Yet it is difficult to know in advance which of today’s ‘brown’ investments will turn ‘green’ and which environmental technologies will prove commercially successful. This becomes more complicated still considering that many listed companies still need to engage in costly and potentially disruptive restructuring if they are to hit net zero goals. (see Fig 2)

All of which means that the potential for capital misallocation - the emergence of asset bubbles on the one hand and unjustifiably cheap assets on the other - grows considerably. While this could give rise to numerous investment opportunities, it could also lead to even more frequent bouts of severe financial market volatility.

None of this is to downplay the importance of the world’s commitment to net zero. It is vital to the world’s future prosperity. Yet the journey to a net zero economy is complex and fraught with risks. Investors face significant challenges – particularly in the initial phase of the energy transition – that could disrupt economic activity and financial markets. Overlooking these threats could be costly.

Download the research paper, Climate crunch: a closer look at the transition risks of net zero

Article attributed to Pictet Asset Management in partnership with the Institute of International Finance

Disclaimer:

This marketing material is for distribution to professional investors only. However it is not intended for distribution to any person or entity who is a citizen or resident of any locality, state, country or other jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, or use would be contrary to law or regulation.

The information and data presented in this document are not to be considered as an offer or sollicitation to buy, sell or subscribe to any securities or financial instruments or services.

Information used in the preparation of this document is based upon sources believed to be reliable, but no representation or warranty is given as to the accuracy or completeness of those sources. Any opinion, estimate or forecast may be changed at any time without prior warning. Investors should read the prospectus or offering memorandum before investing in any Pictet managed funds. Tax treatment depends on the individual circumstances of each investor and may be subject to change in the future. Past performance is not a guide to future performance. The value of investments and the income from them can fall as well as rise and is not guaranteed. You may not get back the amount originally invested.

This document has been issued in Switzerland by Pictet Asset Management SA and in the rest of the world by Pictet Asset Management (Europe) SA, and may not be reproduced or distributed, either in part or in full, without their prior authorisation.

Pictet Asset Management (USA) Corp ("Pictet AM USA Corp") is responsible for effecting solicitation in the United States to promote the portfolio management services of Pictet Asset Management Limited ("Pictet AM Ltd"), Pictet Asset Management (Singapore) Pte Ltd ("PAM S") and Pictet Asset Management SA ("Pictet AM SA"). Pictet AM (USA) Corp is registered as an SEC Investment Adviser and its activities are conducted in full compliance with SEC rules applicable to the marketing of affiliate entities as prescribed in the Adviser Act of 1940 ref.17CFR275.206(4)-3.