Successful colleagues put their naughty hands with fists together in the financial business idea office.

Credit: ArLawKa AungTun/Getty Images/iStockphoto

Private Equity Deals is Ted Seides’ third book. After publishing So You Want to Start a Hedge Fund, drawing on his years seeding hedge funds, and Capital Allocators: How the World’s Elite Money Managers Lead and Invest, Ted said he was going to tackle a subject far from finance. But, over time, he became convinced that a compilation taken from the “case study” interviews he had done with private equity titans on his podcast Capital Allocators could help educate people about an area of finance that now totals $6.5 trillion. Seides argues that a fresh take was needed, at least in part, because of the increase in some pretty harsh criticism of private equity’s role in the economy and whether it truly adds value — or just piles debt on companies and eliminates jobs.

Even if private equity has its stories of success — and failure, Seides says that “over the 20 years ending December 31, 2022, the entire private equity industry generated a compounded, time-weighted return of 14.6 percent per annum, surpassing the 9.8 percent return of the S&P 500 net of all fees and expenses during that period.” So it’s worth reading a few case studies. Here’s one about Greg Fleming, Viking Global Investors, and Rockefeller Capital Management.

The core expertise of private equity is deal-making. After an initial transaction, private equity managers frequently conduct tuck-in acquisitions to expand a portfolio company platform. Buying smaller businesses usually is accretive, as valuations of smaller companies are typically lower than those of larger ones.

Private equity roll-up strategies are predicated on this concept. GPs buy a platform company and conduct a series of related mergers to create a large player that benefits from economies of scale through centralized management, cost efficiency and cross-selling.

Roll-ups bring a host of operational challenges too. Each time a new tuck-in acquisition joins the platform, it must transition its previously independent operations and integrate with the parent. Standardizing operating processes to achieve the desired economic benefits from a transaction includes merging systems, technology, and procedures. Each company purchased comes with its own culture, values, and norms that need to align with the platform for the business to thrive. The more management rolls up acquisitions, the more complex the integration becomes.

For many years, roll-up strategies have targeted registered investment advisors (RIAs). RIAs trace back to the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, which created a fiduciary standard that offered trust and comfort for those seeking financial advice. The industry grew through the 1980s, and interest in advice accelerated after each financial market hiccup along the way. In the 1990s and 2000s, investment banks built large wealth management platforms, led by Merrill Lynch’s “Thundering Herd.”

Wall Street investment bank platforms dominated the RIA space before 2008, but the global financial crisis cast a shadow over the imprimatur of Wall Street institutions. The global financial crisis catalyzed the growth of independent RIA platforms. Businesses like Focus Financial Partners, HighTower Advisors, and Dynasty Financial Partners created homes for RIAs to access the benefits of scale while operating independently of Wall Street banks.

In 2018, Greg Fleming had an idea. He had served as president and COO of Merrill Lynch through the global financial crisis and president of Morgan Stanley Wealth Management for five years afterwards. Fleming saw an opportunity to create a premier independent financial services firm for wealthy families to achieve their goals by combining high-quality wealth management, strategic advice, and asset management services. He wanted to take the best of what he saw in his 25 years on Wall Street and deliver a pure form of client service.

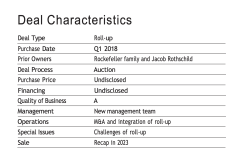

Fleming heard that Rockefeller & Co. might be looking for a new direction. Rockefeller & Co. was a $18 billion multi-generational family office set up in 1882 by legendary industrialist and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller. Fleming partnered with the Rockefeller family and Viking Global Investors to acquire Rockefeller & Co. as the platform for a roll-up under the renamed Rockefeller Capital Management (RCM).

From there, Fleming began executing a roll-up of high-quality RIAs, built a strategic advisory business from scratch, and fine-tuned the existing Rockefeller Asset Management business. RCM went on an acquisition spree, bringing in talent from independent RIAs and bulge-bracket investment banks that fit with its culture of excellence and collaboration. It simultaneously built a robust technology and operations platform required to onboard RIAs efficiently.

In just five years, Fleming grew RCM to $105 billion in assets across 100 RIA teams. It intends to double the number of teams and assets over the next five years. To help achieve these goals, RCM sold a 20% stake in the firm for $622 million to the Desmarais family in April 2023.

The RCM deal is a classic example of the opportunity and challenges in a roll-up. This interview with Greg Fleming describing the business took place on June 29, 2023, shortly after RCM’s recapitalization.

Ted Seides: How did your background lead to you ultimately running RCM?

Greg Fleming: I graduated from law school in 1988. I spent four-and- a-half years as a management consultant at Booz Allen Hamilton and then I went to Merrill Lynch; that was the start of the part of my career that led to RCM. I spent 17 years at Merrill. I started on the investment banking side and ended up in leadership positions—first running the financial institutions group and then as president during the credit crisis. I left right after we closed the sale to Bank of America in early 2009. At Merrill, I spent a lot of time in investment banking in the institutional business, and in the last few years I spent more time with the wealth management business.

When I left Merrill, I took some time off. I taught at my alma mater, Yale Law School; and then I went to Morgan Stanley to work for my former colleague at Merrill, James Gorman, who took over as CEO running wealth and asset management. I was there for six years. We spent a lot of time reconfiguring those businesses. The wealth management business is a huge and important part of Morgan Stanley’s success under James. I left Morgan Stanley in 2016, and when I was looking at what to do next, the confluence of wealth management, investment banking, and asset management were the pieces that I wanted to try to pull together.

Ted: How did the vision for RCM come together?

Greg: My view when I left Morgan Stanley was that there was a window in the marketplace to do wealth management advice for high-net-worth and ultra-high-net-worth clients differently, pulling together comprehensive advice not just on the investment side, but generational planning, tax planning, and investment banking capability. In the United States, so many people make wealth through building a business, so I thought it would be another competitive advantage to be able to provide them with advice on those businesses—maybe sell the business if they’re ready to sell; maybe just give them advice on whether they should sell or not.

And then we have Rockefeller Asset Management, which was part of the original company that we bought that focuses on areas where we can create differentiated investment performance in specialized categories. The pieces all work together. It’s not three different businesses; they’re integrated and they’re all really focused, and that was the vision upfront.

Ted: With that vision of integration across these different disciplines to serve families, how did the deal come together?

Greg: The deal came together around the name. When I heard that we could buy Rock & Co., I pushed hard on that. I had been talking to private equity players that wanted to provide the capital for me to build this vision. Right after I left Morgan Stanley, I was approached by Viking about doing something with them. I liked their vision and how they thought about it a lot. There was a lot of alignment between us around how we would approach it.

I liked the way they manage portfolio companies. They have something they called “GBGM”: “great business, great management.” They find a business they like, they put a great management team in place, and then they leave the day-to-day to you. They’re there on all the big important topics. I was impressed with their vision and the way they wanted to operate, and I can say in year six that it’s been a home-run relationship across the board. So the pieces came together—Viking, Rockefeller and the vision; and we went after Rock & Co. hard.

Ted: What was it on the margin that led you to want to partner with Viking?

Greg: They were clear and consistent on the vision that I had for what RCM could become. They agreed that the best way to build that was to have the advice go through world-class private advisors that we’d recruit; and then they were quite clear on the operating model. I thought, “These guys are thoughtful; they’re aligned; they’re consistent in the way they approach it; they’re straight shooters. They believe in excellence, so they need to hold me and my team to that bar.” It doesn’t always turn out in life that the alignment is consistent and it all works out, but it did here.

Ted: Once you decided to partner with them, you knew that there was this opportunity to buy Rock & Co. How did that deal process come together?

Greg: This was originally the family office of John Rockefeller Sr. back in 1882. It became a multi-family office in the 1970s. At the time we bought it, the primary owners were the Rockefeller family and Jacob Rothschild, who had stepped in to buy Société Générale’s piece in 2008. They hired an investment banker and were ready to sell it. The Rockefeller family was very focused on who would buy it because they care so much about their name. We offered a competitive price, but there was a “get to know you” with the family where they wanted to know what we were thinking of doing with the name and where it would go long term. We had a lot of those conversations with some of the leadership of the family.

We’ve had two members on our board from the beginning to this day: David Rockefeller Jr. and Peter O’Neill. The family rolled some of their ownership in Rock & Co. into RCM. Many of the Rockefellers were clients of Rock & Co. and are clients of RCM. So we are intertwined with the family.

Other positives were the values of the family, the way they approached the world, and the way people view the name. The second generation, John Rockefeller Jr., was the world’s first great philanthropist. The family started the University of Chicago; Spelman College, named after Laura Spelman Rockefeller; Lincoln Center; Museum of Modern Art; Asia Society; land for the United Nations; Grand Teton National Park; Acadia National Park; a hospital in Beijing that’s still there today. The name is everywhere. They were incredible in giving back to the United States and around the world right from generation two, and they’re now in generation seven. They’ve kept it up.

So we appreciated the values of the family and the fact that they cared who was buying Rock & Co.—it wasn’t just about money. Viking and I and the Rockefellers spent time together so that we could all make sure that we had the same vision for what we were going to do with this incredible name. Then there was the usual deal process and negotiation, and we got it. We closed on March 1, 2018, and we were off to the races.

Ted: What was it that you bought at the time?

Greg: It was mostly a family office focused on both the Rockefeller family and other families. A lot of the investment advice was around Rockefeller Asset Management. What we wanted to do right out of the gate was create an open architecture and bring in other managers. So we bought a great name and a lot of talented people at the original Rock & Co.; some long-term strategies in Rockefeller Asset Management, and a set of clients within the family office.

Ted: What were the total assets under management at the time of the acquisition?

Greg: They were about $18 billion.

Ted: With this vision you had to integrate services, there are a lot of pieces in place. How did you start to build on what you first purchased back in 2018?

Greg: We built two of the businesses from scratch. For the business of bringing in private advisors who would work in a broker-dealer format, we needed to build the broker-dealer and obtain all the licenses. There was no strategic advisory, so we needed to start to build a boutique investment bank. The biggest part of our focus in those first few years was the operating platform, the technology platform that would allow us to hire private advisors and bring on their clients. If you’re RCM and you bring in a world-class private advisor who is bringing their clients with them, you’ve got to be able to deliver what you’re promising.

One of the great things about a long career is that you know great people from so many different parts of your life, and we have people running different functions that are as good as you can find anywhere. Because of that, we’ve been able to put in place an operating platform that’s appropriate to support the business of these private advisors and clients that have come to RCM. We have world-class technology. It helps that it’s 2023 and you can partner with different entities in cloud-based solutions. The guy who runs our technology and operations, Mark Alexander, was at Merrill for 24 years and ran technology for wealth management before the sale to Bank of America. Mark is in the process of rolling out new advisor workstations, new mobile apps, and things like that; so even though RCM is a smaller firm than a lot of our major competitors, we’re quite confident that our technology is as good as or better than anybody else’s. All those things were key.

Ted: Let’s dive into the business of growing the assets through financial advisors once you have that infrastructure built. Go back to some of those early acquisitions of teams: how do you find world-class teams and get them to come onto the platform?

Greg: That’s at the heart of what we’ve built. Now we’re six years in, we have over 100 teams and terrific momentum. People can come and see the technology; they can talk to advisors that are already here. So now we’re out there in the field and we’re in the playoffs, but early on, we were just building those things.

Our approach to teams from the start has been the same. They have to have a great book of business. We wanted teams that had worked with their clients for a long time and had loyal clients. We also wanted teams that had clean compliance records and that wanted to be part of Rockefeller.

All our teams work for RCM; they all believe in our culture. We talk all the time about excellence on one hand and a collaborative, collegial, positive culture on the other. If you’re painful—even if you’re really good—we don’t want you here. We have a very positive reinforcing culture; there’s a high bar of excellence, and it’s not for everybody. And when you’re building a company, it’s 24/7 for everybody; people pay that price. One of the things we give back to our team is to say, “Everybody’s going to function that way, starting at the top and across all parts of the firm.” The advisors and teams need to sign on to that too. They’re part of this firm; they’re part of that culture; the business card says “Rockefeller Capital

Management,” and we want them to be proud to carry a business card that has this incredible family name on it. We want them to see what the Rockefeller family has done over seven generations in this country and around the world. We have to live up to that.

We’re looking for all of that—not just a book of business; not just revenues. If somebody wants to monetize their business at the highest possible price, we’d rather they went somewhere else. So we spent a lot of time on this process of finding the right teams in the right cities across the country.

We also want teams that have a burning desire to grow their practice. We’ve got all the things to support these advisors so they can come here and grow. We’ve had teams that have been here for three or four years now and have doubled their book in that time and will probably double it again.

The management structure is also flat. When I was running wealth management at Morgan Stanley, we had 4 million clients. It’s impossible to talk to a lot of clients, but here, I can follow up. I can get to know them. They can come here and have lunch. If you’re the advisor, you can call on senior management to help you with your client. That’s in the drinking water here: everybody’s focused on the client.

Ted: Once you’ve engaged with a team that you’re interested in, how do you get to know them to find out if their values are aligned with what you’re espousing for Rockefeller?

Greg: We really dig in. They do too. In fairness, this is a big decision. Most of the teams that we’re hiring are moving for the first time or maybe a second time. And it’s a huge event for their clients. It’s typically a long courting process—months, even years.

We want people to come to 45 Rockefeller Plaza, walk around, feel the vibe and find out if this is a place they would be comfortable working in. Are our values aligned? Do they seem like the type of people who will walk down the hallway here and say hello to everybody? Do they want to win? Derek Jeter is on our board and I always use him as an example. Derek wants to win in everything that he does. He’s incredibly competitive, but he’s also a really good person with the right values.

Ted: How are these deals structured?

Greg: We want teams that want to come and join Rockefeller forever.

When I was at Merrill 15 years ago, the deals in the industry might have been six, seven, eight years. Ours are double that. If somebody’s looking for something shorter term, that’s not us; just like if somebody wants to maximize current dollars, that’s not us either. There’s a payment in and around 2× revenues for the business upfront that is amortized over the length of the deal.

What we put on top of that is where we differentiate ourselves. The 2× is market competitive, but certainly not on the high end. We want to be competitive and negotiate a fair deal; so we put growth hurdles in for payments that can be made in years three, four, five, seven, ten. We don’t want advisors that are simply looking for the next big check. Our experience over time is that those who grow their practice are relentlessly focused on doing a great job for their clients, which is ultimately the most important variable in the mix.

Ted: How do you think about the return on investment on any one team as it relates to the bottom line of RCM?

Greg: If we bring somebody on for 2× revenues upfront and they deliver their business and grow, that’s a good return for us, and it’s a fair deal for them. If they double their business, even after we pay a growth hurdle, the return to RCM is strong. If you pick the right teams, that blend is a very attractive business model.

Ted: Once you’ve completed an acquisition, the first step in the integration is to make sure the team can bring their clients over. How do you try to increase the probability of that happening?

Greg: We’ve spent a lot of time on this, and we think we do it particularly well. We have an integration and execution group that helps open accounts. They do a lot of the operating and administrative work to bring the clients over. When they join us, we want the team to spend all of their time talking to the clients; and getting Greg Fleming or Mark Alexander or any of the other leadership team here to talk to the clients. The technology and the fluidity of the technology make it easy for the team to move the client over.

The flatness of the management team and the organizational structure also helps. It’s basically a full-court press from day one, bringing all the clients over that the team wants to bring over. We don’t publicize our success rates on this, but we have the team ready to focus on new assets or new clients in months, not years. That’s another key part of the model— and it’s a key part of the economic returns too. It’s like any discounted cash-flow analysis: if the earnings are there later and the payment goes out in front, the internal rate of return (IRR) looks less. For us, the IRR looks better because the business comes sooner. It’s a virtuous cycle all the way around, and it takes the stress off the team. They want their clients to come; they want to get embedded here at RCM; and they want to get moving.

Ted: When you’ve acquired 100 different teams, which bring over 100 different books of investments, how do you integrate all that into something consistent?

Greg: We’ve spent a lot of time on that as well. The teams have been working with their clients for a long time, but we don’t want 20,000 investment options. There’s a transitional period when the clients can come over with their existing set of investments, but over time, if there are only a couple of clients in one option, we might close it off.

We have a decentralized approach, in the sense that we’re hiring great teams that have worked with clients for a long time, so there’s no top- down “This is what you should do.” But there’s also a framework that they can operate within that has a lot of expertise they can draw on—and they do. It’s not all over the map; there’s a consistency across what we do.

Ted: Let’s turn to the strategic advisory component of the business. How did you go about building that from scratch so it could serve your clients?

Greg: There’s a real synergy for the client if you can make it connected. It’s harder in the big firms because the investment bankers are going after very big deals. We might have a client that wants to sell a business they’ve been building for three generations for $200 million or $300 million—it’s a lot of money to them, and obviously a lot of money on an absolute basis, but it’s not a big deal in the investment banking context.

I brought in a few people from my past early on. Something we’ve got better at over time that we didn’t do particularly well upfront is the connectivity there. Early on, we had the bankers and some teams, but not that many. The teams were getting up to speed on everything around their core business, so there wasn’t as much connectivity between Rockefeller Strategic Advisory and Rockefeller Global Family Office. Now we have a fluid, daily connection with concepts or ideas that come from Rockefeller Global Family Office that Rockefeller Strategic Advisory screens. Sometimes the introduction occurs; we get hired to sell a business; we sell the business; and the proceeds go back into the client’s accounts at RCM—it’s a virtuous cycle. And the most important part of that virtuous cycle is that the client benefits everywhere.

We have tremendous momentum today relative to where we were two or three years ago. If you’d asked me 18 months ago where we were on that, we had a long way to go. It’s been in the last year or two that we’ve picked up momentum.

Ted: What was the inflection that created that momentum?

Greg: As always, it’s leadership: getting the right people in the leadership roles. Our co-heads of Rockefeller Strategic Advisory, Steve Valentino and Jim Ratigan, are both veteran bankers. Jim was with me at Merrill; Steve ran financial institutions at Deutsche. They work really well together. Their team is working well with the Rockefeller Global Family Office, with Chris Dupuy and Michael Outlaw and the leadership team there.

Jim, to his credit, hired Steve and made him co-head, and Steve had a set of skills that were complementary to Jim’s. Likewise, Chris promoted Michael Outlaw. The connectivity on the leadership side became much tighter and the expertise became better. We have a better investment banking team now than we did three or four years ago. We also have a broader and deeper set of private advisor teams across the country who have more clients that are running businesses that need advice.

Ted: Let’s turn to the Rockefeller Asset Management side. The strategic advisory and family office businesses are serving these families. Asset management is a super-competitive world that is driven by returns. How have you thought about that business line as it integrates into the whole?

Greg: The mutual fund business is clearly on the other side of any growth curve; that’s not changing going forward. So we need to pick our spots, and we have to perform.

We do a lot of work in ESG, but we’re quite clear to clients and the outside world that while we have ESG portfolios, they’re intended to deliver alpha, full stop. It’s not a nice-to-have; it’s a key part of what we’re doing. We’re also looking for areas that advisors might be able to tap into for clients because there’s less direct expertise for them and fewer options outside Rockefeller. Small cap is one area for that.

We do a lot of work in fixed income. As rates have gone up, this has become one of the big areas of focus for clients. When we hired Alex Petrone, who runs that business, it became a growth vehicle for us. We’re picking our spots. We want to find areas that are high in intellectual capital, high in differentiated advice; and less on the commoditized homogeneous side, where the level of competition is just so high.

Ted: As you’ve been building this out over the last couple of years, what has the relationship with Viking and the Rockefeller family been like along the way?

Greg: The family have been tremendous and they’ve been drawn into it more and more over time. When we bought Rock & Co. and created RCM, for some in the family it might have been the end of an era. For others, they were looking forward. As we’ve scaled the business, treated the brand name as it should be treated, and broadened its appeal, we’ve pulled in more of the Rockefeller family along with us. They’re a wonderful family. They have great values, and they live them. When you get to know the individuals, they’re terrific human beings. The focus on philanthropy is real. It’s everywhere. And they know they’ve got a family name that’s highly regarded across society. It’s one of the few names that’s sustained through generations. Part of that is popular culture—the Rockefeller name has been used in songs over the generations by Frank Sinatra, Jay-Z, Billy Joel, and Bruce Springsteen. It’s part of the fabric of our society. When you get to know the family, you can see why. They’re a really nice group of people. There are more than 300 of them around the world today. We have a great relationship with the Rockefellers, and it’s going to endure.

With Viking, we had the exploratory phase. We did the deal together. We had the alignment of everything I described earlier: the strategy for the firm; how we were going to go about it; capital investment; how we were going to run the firm day to day. It all was aligned from the gate. And that’s how we’ve operated for the last five-and-a-half years. They’re involved in everything that matters. On a day-to-day basis, they leave it to us. We’ve agreed on major financial and other objectives, and we’ve hit them. So they continue to be very supportive. They’re very happy with the investment. It’s been a great partnership. It was envisioned the right way upfront and it’s performed that way.

Ted: What have been some of the biggest challenges along the way?

Greg: One of the big ones was building up RCM and making sure we could deliver. We had the Rockefeller name; very sophisticated clients; very sophisticated private advisors managing hundreds of millions or billions of dollars of people’s wealth. These are all people of real stature. You absolutely have to deliver. The technology and the operating platform and all the services that we were going to need to create this broad-based advice that advisors could provide to clients—all of these had to be built. So that was a real pressure, and it’s taken years to achieve.

It happens brick by brick: something gets built and then you move on to the next thing. We’re in year six and we’re still building. In year 12, we’ll still be going, but we’ve already made a tremendous amount of progress. That was definitely a big focus upfront: we had to get going on delivering on what we said we were going to do, because otherwise you hire the advisor, the client struggles, and the whole thing stops.

Then there were some other challenges related to horizontal connectivity. One of the lessons of my career is that bad things sometimes happen because of an absence of horizontal connectivity across a firm. Looking back, there were major challenges at Merrill from a risk standpoint because of a lack of horizontal connectivity. We have a ton of it here, and we talk about it constantly. But that doesn’t happen by magic. You talk about it—you can say, “This is what we want to do and what we want people to do,” but you have to show them, and you have to reinforce it. It has to start working day to day.

Early on with Strategic Advisory and Rockefeller Global Family Office, the horizontal connectivity wasn’t great. The advisors were talking to their clients, but we were not bringing it together well. There was a whole series of things that needed to be tied together more tightly. It’s a lot better, but it’s a journey. We still have more to do there. Among the 1,200 people at RCM, many of them use the phrase “horizontal connectivity” and are trying to make that happen. If the phone rings anywhere in the firm and there’s an issue for a client, that person knows they’re supposed to try to help. It’s not, “Wait a minute—this doesn’t fit into my department.”

Ted: How do you take that from not great to good to great?

Greg: It’s leadership at my level, but it’s also the people—my team, the senior team, and the team working for them. It’s making it part of everybody’s mindset here. Somebody once said to me earlier in my career, “If there’s something you’re trying to push at—whatever the size of the organization—it’s like pouring water on sand. You put a little water on the sand, and it disappears—the sand’s still there. But you just keep pouring the water on the sand and over time, it starts to gain traction.” That’s what we do here. We are constantly aligned on the same themes: critical success paths, horizontal connectivity, excellence, collaboration, and collegiality. All of these things are in the drinking water here.

We have an award called the Enterprise Connectivity Award that we created a couple of years ago. We pick from seven to thirteen people each year. We review the nominations at a senior level, but they come through the firm—and those people get an extra bonus and recognition. We have an event with them where they have a drink with the whole leadership team; we introduce them to our board; they get a plaque that goes on their desk. We want that to be one of the greatest things that people aspire to here. It’s rewarding the people who are out trying to make things happen—Malcolm Gladwell calls them “connectors.” We put them in the spotlight, and I do everything I can to make this the best possible award.

So when you were asking, “How do you get this horizontal connectivity? How do you get people to act this way?”, that’s how we do it.

Ted: Today, five or six years in, what does the business look like?

Greg: The assets under management are well north of $100 billion; so we’ve scaled. One of the benchmarks that I look at is the footprint. We wanted to take this magical name and put the footprint out across the United States. We’re in 45 cities now, which is probably more than I had anticipated upfront. That’s the magic of the United States. Wealth and success are in every pocket of the country, including some of these new places like Austin, Charlotte and Nashville. If you’d asked me how many cities we would be in five-and-a-half years ago, I would have said 30 or 35. And having scale in all of those places doesn’t mean a huge number; it could be just five teams.

So if you have five teams on average in 50 cities, you have 250 teams. Right now, we’re about halfway to where we want to be. The inorganic side of our strategy is important. But at some point, we’ll have done most of what we want to do inorganically. And that magic organic growth, that’s the future of RCM. Viking and I talked about that in 2016 and 2017: creating an entity that would have advisors that could grow organically year in, year out—which is the holy grail in the industry. People struggle to do that. But we think we can do it on a differentiated basis as far as the eye can see.

Ted: How do you catalyze that organic growth when it’s so hard for the industry as a whole?

Greg: You have to have it everywhere. It’s like your earlier question, “How do you get the horizontal connectivity everywhere in Rockefeller?” Same thing: we talk about organic growth constantly. The second award we’ve created is an Organic Growth Award, which we’re about to roll out. We want to recognize people who are particularly good at organic growth, but not reduce the horizontal connectivity. We want the whole firm involved. We have a great legal and compliance department, a great HR department—we want them focused on organic growth too. That doesn’t mean compliance can’t say, “Sorry, we can’t do that.” They have to do that sometimes. But it does mean they can try to do something that works for the client before they just say no. The whole firm can focus on how we do more for clients and how we get more clients in. It’s everywhere.

Ted: You recently recapitalized the business—how did that come about and what did the deal look like?

Greg: We had been approached by other families before, but we were focused on building the firm and growing. We were trying to build something that will last for a long time, so we were very careful about this analysis. When the Desmarais family put the concept out there, I was immediately interested because of the alignment of values and long-term orientation that I knew they would bring. I’ve known Paul Desmarais Jr. since my Merrill days. We had an international advisory board that he was on, and I ran that board day to day, so we got to know each other well. That was 20 years ago. Andre Desmarais is the other co-chairman. They’re the second generation of Desmarais that I’ve come to know quite well in the last decade. And they’re terrific people with terrific values.

So when they put the concept out there, I went to Viking and said, “This could be an interesting partner. They hit all the right buttons: values, long-term orientation. They love our business model. They love the Rockefeller name. They love the growth model.” On the Rockefeller name, Andre’s mentor—literally one of his close mentors growing up— was David Rockefeller Sr. The connectivity there was unreal; they did a lot of things together. So there’s a lot of history between the Desmarais and the Rockefellers.

We started last fall, but these things always take time. It began to pick up momentum toward the end of the year and we ended up announcing it in early April. We wanted no more than a minority investment. Viking is quite happy with where we are and where we’re going, so they weren’t interested in selling more than 20% or so. All the stars aligned on the things that matter.

Ted: The Desmarais investment is public: $622 million. Where did you come up with that number?

Greg: Having negotiated north of 100 deals in my career, that’s part of the sausage making—the back-and-forth on this point and that point. That’s all it is. There’s no magic around one number versus a slightly different number. It was intended to be a minority stake in and around 20%; and then we just had a lot of back and forth. There’s primary capital going in the business, and they’re taking down the ownership of some of the people here.

So Andre Desmarais and James O’Sullivan—the CEO of IGM, which is an entity in the power world that took a stake in RCM—they’re on our board. And Jeff Orr is a special advisor to our board. I’ve worked closely with him, and we wanted to make sure that we had Jeff in our boardroom. So there are two board seats plus Jeff as special advisor.

Ted: How are you thinking about spending the capital from the deal that’s coming on the balance sheet of Rockefeller?

Greg: It’s more of the same of what we’ve been doing. We’re going to stay focused on the Rockefeller Global Family Office buildout—that’s first and foremost. We have bought two RIAs in smaller acquisitions on a negotiated basis. The reason I point that out is if we have an investment banker call us up and say, “We’re selling an RIA, here’s the math—do you want to be part of the process?” I almost laugh. That’s not for us. We need them to want Rockefeller. We need to get to know each other. There has to be the fit. We’re not going to participate in an auction. But we’re well capitalized, so we can do things that might come up.

Ted: Over the next five or six years, what are your goals and objectives for the business?

Greg: A lot is “more of the same.” And that’s a good timeframe that you laid out. Over the next five or six years, we will get to the vision that Viking and I had in 2017. We will be scaled. We will have 200-plus teams in 50 cities. We’ll have over $200 billion in assets. We’ll have done a lot of the building that we need to do to support our private advisors and make the promises to their clients. We’ve done a lot already, but there’s always more to do. That’s the end game from the original vision. I’ll feel good if we get there in 10 years. And then the question becomes, “Okay, where do we go?” You could take this name and you could do this really well with a partner in different parts of the world. Rockefeller is a huge name in China. They’re known in Europe, the Middle East, and South America.

In five or six years, we want to have finished the original mandate, which was to create a best-in-class firm offering comprehensive advice through world-class private advisors to high-net-worth and ultra-high-net-worth clients across all of the United States, with the ability to counsel them if they built that wealth through a business, and the ability to offer products on the asset management side that are unique to Rockefeller, but on an open architecture basis. So that vision should have been realized.

Ted: When you put your deal hat on, how do you think about the ultimate exit strategy of the business?

Greg: The Desmarais were step one and the alignment of everything was crucial there. If we could have another great family come in and be part of this alongside the Rockefellers and the Desmarais, that would be terrific. We’re building something that we would like to endure. It’s a great firm. It’s a unique firm. People love working here. We want to figure out a transition on the corporate side that allows that to take place. The public market is always an option, but I think this is a great business to keep private.

We want to make sure that the essence of RCM can endure for a long time. One of the great disappointments of my career was having to sell Merrill Lynch. Merrill had a business mix and a brand that should have endured forever, and it didn’t. I was part of that leadership team. So here I’d like to build something where someday I go down on the elevator for the last time and it endures.

Ted: What are your biggest lessons learned from this experience?

Greg: If you’re going to build something that’s great, almost from scratch, you have to be all-in 24/7, or it’s going to be very hard to create excellence. When I look at the likes of Apple or Amazon, a lot of blood, sweat and tears go into creating something that incredible. That’s true about excellence in any aspect of life. And it’s clearly true here, which is why we’ve created this culture where everybody wants to be part of excellence. We try to have no exceptions to that, so that everybody holds the bar really high.

But it’s been intense. You’re all-in, all the time. There’s that feeling of the need to make things happen on an ongoing basis. That’s why it’s nice to be where we are now. I once asked a good friend of mine who started one of the great companies in the world today from scratch, “What was your hardest year?” He said, “The first year.” Then I asked, “What was your second-hardest year?” He said, “The second year.” I thought, “Okay, I get it.” You have to be all-in, and you have to focus on excellence in everything. One of my favorite quotes is from Vince Lombardi, the famous football coach: “Perfection is not attainable, but if we chase it, we might just catch excellence.” We live a lot of that at RCM.

Ted: One last question: what’s your favorite aspect of private equity?

Greg: My favorite aspect of private equity is the role that it’s played in the competitiveness of our economy. I’ve had a great experience with it. I think that private equity done well becomes an intellectual capital partner in something like RCM. And look at what we’ve done here—all the people that we’ve hired who are part of a company they’re proud of. That’s a great part of private equity. There are certainly challenges in private equity and criticisms in the political world—it gets hit from all sides—but I think it’s part of the reason our economy is as vibrant as it is.

Excerpted from Private Equity Deals: Lessons in investing, dealmaking, and operations from private equity professionals.