The Federal Reserve has signaled that it expects to cut rates sometime this year. The timing of the first cut is up in the air. Prior to Wednesday’s FOMC meeting, fed fund futures had been pricing in a chance of a cut at the next meeting in March, but Powell strongly implied that was too soon and instead indicated May or June is more likely.

Still, most economists think that absent an inflation resurgence, the Fed is going to lower rates this year.

On January 2, my colleague Joe Kalish featured studies on several asset classes, including equities, around first rate cuts. This report dives into more detail about how the stage of the economic cycle at the time of the first cut has affected market performance.

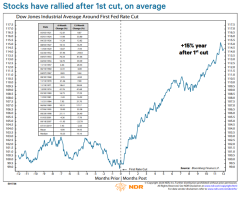

The bottom line is that the stock market has tended to rally in the year after the first cut.

The phase of the economic cycle, however, has mattered. The worst performances have come when the economy was not in a recession at the time of the first cut — but was poised to fall into one in the next year, on average.

Two caveats: First, we use first cut dates, not the start of easing cycles. NDR defines an easing cycle as two cuts without a hike in between. While consensus is calling for multiple cuts in 2024, no one knows beforehand.

Second, we use the Dow Jones Industrial Average because it has more history than the S&P 500, but the trends are the same.

One tumble & a jump?

Assuming the Fed cuts rates at the June 12 meeting and the DJIA remains at its current level, the index would be up 11.3 percent from a year earlier. That would rank sixth out of 25 cases.

The DJIA has rallied after the first cut, adding an average of 9.9 percent six months later and 14.4 percent one year later. While gains have been even stronger after the second cut, supporting the “two tumbles and a jump” adage, the market has tended to rally after the first cut.

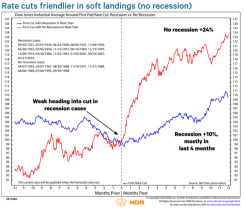

Recession vs no recession

Not surprisingly, the DJIA has rallied more when a recession has not occurred within a year before or after the first cut. See the chart below. In the year before, the DJIA has lost an average of 4.2 percent during recession cases versus a gain of 6.6 percent during non-recession cases. Perhaps surprisingly, a year after the first cut, the DJIA posted gains regardless, although average gains were higher in non-recessions (23.8 percent) than recessions (9.8 percent).

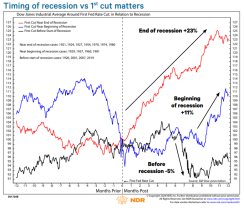

Recession status matters

The reason the market has managed to rally in recession cases is that historically the Fed has not cut until near the end of the recession. The stock market bottoms about four months before the end of the recession. By the time the Fed has stepped in, the damage has been done. Rate cuts likely aided recoveries but were probably not the catalysts in many cases.When the first cut came near the end of the recession, the DJIA soared a mean of 23.3 percent a year later. That chart is below. When the first cut came near the beginning of the recession, the market tumbled an average of 10.5 percent six months before and gained only 2.4 percent six months after — but was up 10.7 percent one year later.

Second, a recession appears unlikely to start before mid-2024, so there may be no recession and a strong bull market — or a recession and a bust for the Fed.

Ed Clissold is chief U.S. strategist at Ned Davis Research