Tarred by its role as the chief enforcer of austerity during the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s, the International Monetary Fund spent much of the ensuing decade trying to repair relationships with Asian governments. So, Fund officials considered it no small coup when they co-hosted a major conference, dubbed Asia 21, with the South Korean government in July to showcase the region’s economic resurgence and consider the lessons that Asia can offer policymakers in troubled Western economies.

Winging his way back from Daejeon, South Korea, IMF managing director Dominique Strauss-Kahn took time to blog about the event and claim a new era in relations between the Fund and Asian governments. “A remarkable event took place that enabled the world to hear the voice of Asia,” he announced in a post on the IMF Web site. “Just as there is a new Asia, there is a new IMF.”

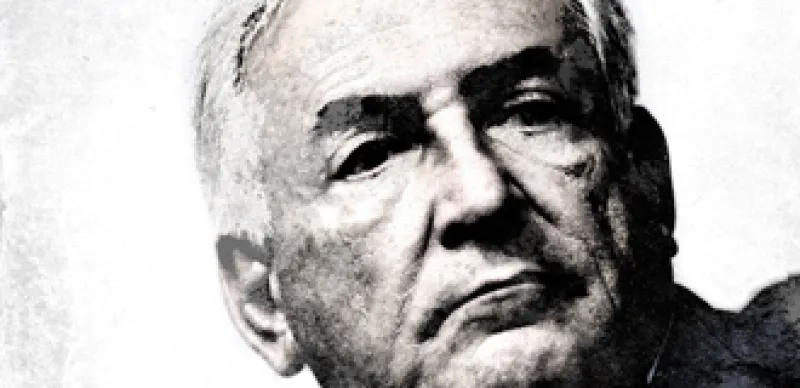

There is indeed a new IMF taking shape under the leadership of the charismatic Strauss-Kahn, a former French finance minister, and wooing Asia to trust the Fund’s analysis and expertise is just the latest step in his rebuilding of the institution.

[Video Caption: The IMF said Asia is leading the global recovery and global growth is likely beat its forecast of 3 percent this year. "Even though the recovery is stronger than expected, it is also very fragile, especially in advanced economies," Dominique Strauss-Kahn, managing director of the IMF told CNBC. Airtime: Wed. Jan. 20 2010 | 4:50 AM ET ]

When Strauss-Kahn arrived in November 2007, the Fund seemed to be fading into irrelevance: Developing countries didn’t need its money, and the big industrial powers routinely ignored its advice. But using his economic instincts and political acumen, the managing director, or “DSK,” as he is known from the way he signs his memos, moved quickly to restore the Fund to its role as a linchpin of international economic policy coordination and crisis management. The 61-year-old Frenchman was one of the first policymakers to call for government stimulus spending to counteract the slump, in January 2008, a stance that would eventually be adopted from Washington to Beijing. He waded fearlessly into the debate over the financial sector’s failings and made the Fund a significant player in regulatory reform of the global financial system. And he lobbied tirelessly for a major increase in IMF resources to deal with the scale of the worldwide economic crisis. His efforts were rewarded at last year’s Group of 20 summits in London and Pittsburgh when leaders of those countries agreed to treble the IMF’s resources, to $750 billion, and mandated the Fund to lead an ambitious economic surveillance program and develop innovative new lending schemes.

“The IMF is clearly back at the center of international economic policymaking, and you have to give a lot of the credit for that to Strauss-Kahn,” says Garry Schinasi, a former IMF official who is now a visiting fellow at the Brussels think tank Bruegel. “If there was ever a time the IMF needed a politician’s touch, this is it.”

As Strauss-Kahn heads into October’s annual meetings of the IMF and the World Bank in Washington, his agenda is as ambitious as ever. The Fund is playing a leading role in economic policy coordination, chairing a so-called mutual assessment process among the G-20 countries that seeks to foster more-balanced growth around the world and avert the risk of a fresh collapse. Building on the Fund’s role in supporting a €750 billion ($965 billion) European Union bailout of heavily indebted countries this spring, Strauss-Kahn is pursuing new ideas on how the Fund might work in the future with regional blocs like the EU or the Chiang Mai Initiative, a liquidity-pooling agreement among key Asian central banks. He and his IMF colleagues are preparing to unveil new insurancelike facilities that could disburse money quickly to crisis-hit countries. And above all, he is trying to pull off a long-promised reallocation of the Fund’s quota shares and voting rights to give more influence to rising powers like Brazil and China. If Strauss-Kahn and Fund officials manage to keep the momentum behind these initiatives going, they will be taken up by G-20 leaders at a potentially pivotal summit meeting in Seoul in November.

“Each of these initiatives and programs are unprecedented in their own ways,” says Domenico Lombardi, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington. “But it is the potential for a breakthrough on the quota and voting right reforms that is probably the most relevant.”

This quartet of initiatives, if successfully completed, would amount to the most far-reaching remake of the IMF and the international monetary order since the original Bretton Woods system broke down in the early 1970s. In effect, they would push the Fund a step closer to becoming a true global lender of last resort, a role that economist John Maynard Keynes, one of the Fund’s architects, originally intended.

That would be more than enough to tax and test anyone’s leadership, even someone armed with Strauss-Kahn’s political skills. And on that score, as if there isn’t already enough drama and high stakes involved, Washington and Paris are both buzzing with speculation that the managing director may quit the Fund by the middle of next year to pursue a bid for the French presidency.

There would be no small irony if he did so. Strauss-Kahn campaigned unsuccessfully for the presidential nomination of his Socialist Party in 2006, losing out to former Environment minister Ségolène Royal. After conservative Nicolas Sarkozy defeated Royal in the 2007 election, he lobbied to win the IMF post for Strauss-Kahn, regarding it as a key position for France — and a convenient exile for his political rival. But Strauss-Kahn’s deft handling of the crisis, including winning a major role for the Fund in the EU bailout of Greece, has only enhanced his standing.

One of the biggest factors in the IMF’s revival is the ascendancy of the G-20, a collection of leading developed and emerging powers that has supplanted the Group of Eight as the premier forum for international economic policy coordination. As a larger body that is less susceptible to the dictates of Washington or European capitals and whose diversity makes consensus difficult to achieve, the G-20 needs an organization with the legitimacy and institutional capacity to support its work. That is a role for which the IMF, an economic and financial body with 187 member countries, is almost tailor-made.

The Fund’s first G-20 task is arguably its most challenging one: coordinating the mutual assessment process. The MAP, as it’s called, is a new peer review of the national economic policies of the G-20 countries, aimed a promoting “durable recovery with strong, sustainable, and balanced global growth,” in the words of the Pittsburgh communiqué. The intention is to avoid a repeat of the massive imbalances — a gaping U.S. current-account deficit and soaring surpluses in countries like China and Germany — that many economists believe contributed to the global financial and economic crisis.

The aim is noble, but skepticism of the MAP runs high. Most international policy coordination efforts have ended in tears, or been quietly abandoned, since the original Group of Five began meeting in 1975. Just four years ago, under Strauss-Kahn’s predecessor, Rodrigo de Rato, the IMF launched a high-profile multilateral surveillance exercise involving the U.S., the euro zone, China, Japan and Saudi Arabia in a bid to reduce global imbalances, only to have the process fizzle out a year later. In effect, Washington ignored the Fund’s recommendations that it take steps to boost the U.S. savings rate, and Beijing paid no heed to IMF arguments that the renminbi should appreciate.

This time around, hopes for the MAP received a boost when the Obama administration followed through on its Pittsburgh commitment and the U.S. became the first country to submit its policies to peer review by the Fund and the other G-20 countries. And with the MAP being one of the first major policy initiatives by the G-20, there is a lot at stake for the group’s own legitimacy. “This is surveillance at the highest level, and while it is a soft framework in that there is no obligation on the part of the individual G-20 countries, it is nevertheless unprecedented in its scale and objectives,” Lombardi notes.

After a first round of assessments, the IMF delivered its policy option scenarios to the G-20 leaders at their summit meeting in Toronto in June. Strauss-Kahn underscored the stakes involved when he told the leaders that “appropriate collective action could increase global GDP by 2.5 percent over the medium term.” The initial response, though, wasn’t encouraging. Summit participants clashed openly, with Prime Minister Stephen Harper, the meeting’s host; German Chancellor Angela Merkel; and new U.K. Prime Minister David Cameron urging quick action to rein in deficits while President Barack Obama, with support from Japan and India, argued that the policy emphasis should remain on stimulus for the near term. The leaders papered over their differences by calling on members to cut deficits in half by 2013, but to move cautiously on spending cuts so as not to derail the recovery. In the months since Toronto, the underlying problem appears to be getting worse, with the U.S. trade deficit increasing sharply in June while surpluses soared in China and Germany.

The IMF has been squaring the updated forecasts of the individual countries with its own projections to present a refined analysis at the annual meetings. The MAP’s day of reckoning will come at the Seoul summit, where G-20 leaders will have to decide whether to adopt the Fund’s final policy recommendations. “Any global recovery will inevitably require shifts in demand, not only between the public and private sectors within countries but especially across countries, between the surplus and deficit countries,” explains Morris Goldstein, the Dennis Weatherstone Senior Fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington. So far, however, there is little sign that G-20 governments are willing to modify domestic policies for the sake of global harmony. China appears unwilling to allow a significant appreciation of the renminbi after letting it rise slightly just before the Toronto summit; Germany seems content to point to its second-quarter growth spurt; and the U.S. has yet to put forward a plan to reduce its record $1.3 trillion budget deficit.

Another key issue in Seoul — arguably the most important in the eyes of the emerging-markets G-20 countries — is the matter of reallocating IMF quotas and voting rights. The distribution of quotas is the crucial formula that determines everything from a country’s influence on IMF policies to the amount of hard currency it can borrow from the Fund in a crisis. The U.S. and Western Europe have had a preponderant share of quotas since the Fund was established at the end of World War II, and although IMF officials and major shareholder countries have been promising a fairer redistribution for as long as just about anyone can remember, adjustments have not kept pace with changes in the global economy. In 2006 shareholders agreed to an ad hoc quota increase for China, Mexico, South Korea and Turkey, and two years later they revised the quota formula to increase the voting shares of dozens of developing countries. Still, big disparities persist. Belgium, a country of 10 million people, holds more weight in the IMF than Brazil, whose population is 20 times greater and whose GDP is 5 times larger.

A new quota review is under way, and the G-20 has set a target of shifting at least another 5 percent of allocations to emerging-markets countries like Brazil, Russia, India and China by the end of 2011. “All eyes are turning to Seoul for delivery,” says IMF first deputy managing director John Lipsky. Many outside observers think that after so many fits and starts, this time the odds look good for a deal. “In the past some key shareholders were always able to limit the erosion of their quota and voting shares, but this time is likely to be different, with a pretty substantial and symbolic reallocation of the quotas, mostly away from Europe to Asia,” says Brookings’ Lombardi. The main resistance is coming from European countries, but the fact that the European Union was forced to come cap in hand to the IMF earlier this year to help resolve the Greek sovereign debt crisis has fostered rising expectations of a quota deal.

In addition to quotas, a deal on IMF governance probably will also involve seats on the executive board, where the true power at the Fund lies. The 24-member board currently has five so-called appointed seats, held by Britain, France, Germany, Japan and the U.S. The remaining seats are known as elected ones. Of these, China, Russia and Saudi Arabia hold solo seats. The other 16 seats are nominally elected, with the chairing country representing up to a dozen other nations. In practice, several European countries have had locks on the seats for decades.

A deal on a revamped board is expected to trigger a long-overdue scaling back of European representation, with several of the elected chairs, such as those held by the Netherlands and Belgium, ceded to some of the bigger emerging-markets countries, like Brazil or India. In addition, China is expected to take over one of the five powerful appointed chairs. The question is, whose? One idea being bandied about is for France and Germany to assume a joint chair. Ironically, Strauss-Kahn suggested just that to German officials a decade ago when he was the French finance minister, recalls Otmar Issing, a former Bundesbank and European Central Bank official who now heads the Center for Financial Studies in Frankfurt.

“Whatever form the redistribution of chairs takes, the point is that the ‘shares and chairs’ is where the true power and influence within the Fund lies, and that is why this is so important to the BRIC countries, who stand to benefit the most,” notes the Peterson Institute’s Goldstein. “But it is really just as important to the Fund itself, for it will lack legitimacy until this long-standing governance deficit is addressed.”

The overall objective of the IMF’s quota reforms is to make the key emerging-markets countries feel empowered to influence Fund policies, while the MAP aims to create an international policy framework for more-balanced global growth. Fund officials hope both initiatives will ultimately help prod those key emerging-markets countries to shift away from their export-driven growth model, which involves aggressive currency intervention to keep their exchange rates down as well as the accumulation of massive foreign currency reserves. Fund officials, taking a position backed strongly by the U.S. government, believe those policies have distorted capital flows and interest rates and added fuel to the fire of the financial crisis.

A similar line of logic is driving a radical rethinking by IMF officials of the Fund’s lending programs. Unlike the traditional standby arrangement, under which the Fund negotiates an agreement with a crisis-hit country and disburses liquidity in tranches as the country meets benchmarks of economic reform and performance, officials want to move the thrust of lending resources to crisis prevention programs that would provide liquidity rapidly to countries facing the risk of contagion and capital flight — a “global financial safety net,” as Strauss-Kahn and South Korean Finance Minister Yoon Jeung Hyun described it at the Daejeon conference. The Fund has been tinkering with similar ideas ever since the Asian financial crisis, but most efforts found no takers: Either the conditions were too stingy, or countries didn’t want to go to the Fund for fear of being perceived by the markets as weak. But the IMF scored a breakthrough last year with the introduction of its flexible credit line. The FCL allows countries with track records of robust fiscal and monetary policies to sign up for a big credit line. Mexico, Poland and Colombia did just that in the spring of 2009, to the tune of $40 billion, $20 billion and $10.4 billion, respectively. The existence of the credit lines, which were never tapped, may have helped those countries weather the storm in financial markets.

Strauss-Kahn has already said that the IMF is looking into enhancements to the FCL, to be discussed at the annual meetings; these include expanding its duration and removing the cap on access to IMF resources. Officials hope the FCL will act as an incentive for countries to improve their policies enough to qualify for it. And for those countries coming just shy of the qualification criteria, the IMF is studying a possible precautionary credit line, which would work in a similar fashion but with some conditionality attached.

Such insurance-type programs have a larger objective. If countries are confident of being able to call on the IMF’s massive resources to stem a sudden bout of capital flight, then maybe they won’t feel obliged to maintain a hefty pile of reserves as self-insurance. The need for protection against the vagaries of capital flight is certainly justified. According to the Washington-based Institute of International Finance, net capital inflows to the emerging-markets economies fell from $929 billion in 2007 to $466 billion in 2008 and just $165 billion in 2009.

The Fund is working with G-20 chair South Korea to study the feasibility of a new systemic liquidity facility. Conceptually, the facility would operate in much the same way as swap lines among central banks. The Fund would rapidly disburse large-scale liquidity with one or several Asian central banks, which might group their foreign reserves under the Chiang Mai Initiative. It is pretty heady stuff and will require no small work, considering the sensitivity of intra-Asian politics between the main creditor central banks and those most likely to need the liquidity.

Strauss-Kahn has said the Fund has been looking into what he describes as a broader systemic risk mechanism, under which groups of qualifying countries might be offered IMF help at the same time. The idea is to avoid waiting to be asked for help, by which time financial conditions are likely to be much worse because of the stigma of turning to the Fund in a time of distress. The concept sounds a lot like the Federal Reserve Board’s Term Auction Facility, which was introduced to get around banks’ reluctance to be seen tapping the discount window. One Fed official suggests that the origins of the FCL and the proposed systemic liquidity facility lie in the swap lines that the Fed offered to South Korea and a handful of other countries in late 2008. “It has all the look and feel of the Fund becoming, somewhat by stealth, a global lender of last resort,” says the official.

All sorts of hurdles litter the path to the new IMF. The Europeans might cling to their power within the Fund or balk at policy recommendations from the MAP. The Chinese could continue to take their time in moving the renminbi to a more realistic exchange rate. The new, precautionary liquidity lines might fail to provide enough incentives to persuade emerging-markets countries to stop building their own reserve stockpiles.

The regional arrangements being explored by the Fund may present the greatest political difficulties. At the end of the day, which institution — the IMF, the EU or the Chiang Mai central banks — will be the dominant decision maker?

The IMF’s collaboration with the European Union has gone reasonably smoothly so far. Many European officials insist that the IMF’s involvement in Europe will only be transitional, ending after the three-year mandate of the European Financial Stability Facility, the new bailout fund for euro-zone members that was set up with €440 billion from euro-area Treasuries and backed by a pledge of €250 billion from the IMF. But others, such as Jean Pisani-Ferry, a former EU and French official who heads the Bruegel think tank in Brussels, believe the IMF may be in Europe’s institutional architecture to stay. And that inevitably raises the question of whether there will be serious conflicts down the road. “You have to wonder if the situation could arise in which the IMF differs with the ECB over its monetary policy when it comes to assessing the adjustment program of a country whose currency is the euro,” says former ECB official Issing.

But probably the biggest question mark hanging over the IMF’s far-reaching agenda is Strauss-Kahn himself: Will he stick around to see the reforms through, or will he leave the Fund sometime next summer to enter the French Socialist Party primary for the right to challenge President Sarkozy in the 2012 election?

It is an ambition Strauss-Kahn has long held, something he confided to Institutional Investor in 1997, when he was Finance minister. He himself set the speculation in motion early this year when he was asked in a French radio interview whether he would consider a run. Though he said he intended to see out his term at the IMF until the end of 2012 — some seven months after the French presidential elections that spring — he coyly added, “But if you ask me if, under certain circumstances, I would reconsider my options, then yes, I could imagine doing that.” National polls in February and March stoked public interest when they showed Strauss-Kahn leading Sarkozy by 52 to 48 percent; another poll, published in Paris Match, showed that an astounding 76 percent of the French public had a positive view of the IMF boss.

When Strauss-Kahn campaigned for the Socialist nomination in 2006, he garnered barely 20 percent of the vote, far behind Ségolène Royal’s 60 percent. Afterward, he criticized the left wing for the defeat, contending that the party needed to overhaul itself and develop credible policies to keep France economically competitive. For some Socialists, that view merely confirmed Strauss-Kahn as gauche caviar — a rich champagne socialist who would be more naturally at home on the right. His probable chief rival for the nomination, Socialist Party secretary general Martine Aubry, is the left’s standard-bearer and will be counting on the unions and left-leaning activists to get out the vote.

Yet, as the most market-friendly reformist among the Socialist candidates, Strauss-Kahn has credibility where his party is weakest. His supporters are already undertaking some of the preliminary groundwork to ensure that he will have the means to run as a candidate if he chooses to do so. The only question in the minds of his supporters is simple: Does he want it?

Philippe Moreau-Defarges, a political scientist at the French Institute for International Relations, regards Aubry as the candidate to beat. “Strauss-Kahn is seen as the most clever of the pack, but he is a technocrat and he is viewed with no small dose of suspicion as being too Anglo-Saxon in his views by many French people,” he contends.

To run in the Socialist Party’s primary next autumn, Strauss-Kahn would have to return to France by the early summer of 2011, or shortly after the spring meetings of the IMF/World Bank and the spring G-20 meeting. “There is more uncertainty in whether he is going to run than is being suggested, and I think for now he is genuinely keeping his options open,” says Pisani-Ferry, a friend of Strauss-Kahn’s since their work together at the Finance Ministry in the 1990s. In the meantime, Pisani-Ferry adds, the question about his presidential ambitions maximizes his political leverage with the EU, given that when he is negotiating with them, they may be talking to the next president of France.

Adding spice to the speculation over Strauss-Kahn’s political ambitions, France is the host country of both the G-8 and the G-20 next year. That puts none other than Sarkozy in the driver’s seat to set the policy agenda for the IMF and its managing director. The French president has already called for a new Bretton Woods pact to reshape the international financial architecture and replace the U.S. dollar as the main reserve currency. He also wants to push for heavier regulation to contain hedge funds and combat market speculation.

Whether he leaves to challenge Sarkozy or stays at the Fund, where he would almost certainly be reappointed to his post for another four years in 2012, Strauss-Kahn will probably be the last European to head the institution under the transatlantic arrangement whereby a European has run the IMF while an American has headed the World Bank. With the global economy’s center of gravity shifting inexorably toward Asia, the widely held assumption is that the next IMF managing director will be Asian, and probably Chinese.

According to the latest speculation, the most likely person to succeed Strauss-Kahn is the managing director’s current special adviser from China, Zhu Min. A former official from the People’s Bank of China, the Chinese central bank, and a former executive at Bank of China, Zhu is considered one of China’s new stars on the international policy scene. “He has been rising rapidly through the ranks and is a player,” says one Fed official who has worked with Zhu. “He knows our system well and how things work in an institution like the IMF, and he is nobody’s fool.”

Since his appointment to the Fund earlier this year, Zhu has been making his presence felt. IMF insiders say he had a hand in Beijing’s decision this summer to release the IMF’s annual Article IV surveillance report on the Chinese economy, which included the view of Fund economists that the renminbi is undervalued. It was the first time China had consented to release its IMF report in four years. According to one Chinese source close to policymakers in Beijing, Zhu is likely to be appointed as a deputy managing director later this year. Assuming that quota reform goes through, China intends to ratchet up its engagement in the Fund along with its financial support, most likely by taking another private placement of IMF bonds. (Beijing bought 32 billion special drawing rights ($50 billion) worth of IMF bonds last year.) Such a deal could move China, which currently has a 3.65 percent stake, past France, Germany and the U.K. to become the third-largest shareholder in the IMF, behind the U.S. and Japan.

But an internal path is not the same as the inside track. If Strauss-Kahn leaves and the IMF needs to find a new head in 2011, the timing may be too early to allow Zhu to rise to the top slot. IMF members have already agreed that the selection of the next managing director should be made through a transparent and competitive process, so a backroom deal on the basis of Zhu’s nationality would be a tough case to make. Brazil and India, among other emerging-markets countries, are said to be ready to field candidates if Strauss-Kahn should make an early exit.

Such jockeying may be premature, though. Strauss-Kahn’s decision is still many months away. Friends say he has come to genuinely love the IMF job and believes in the potential for the Fund to become the linchpin of a new international monetary order. Fulfilling his ambitious agenda would go a long way toward that end — and would seal his legacy.