Dissatisfaction with low interest rates and sluggish growth in the developed world is luring bond investors to emerging markets. In the first ten months of this year, the 929 emerging-markets bond funds tracked by Cambridge, Massachusetts–based EPFR Global pulled in $49.5 billion in new assets. That’s more than five times the $9.5 billion they received in 2009 and 52 percent of total emerging-markets bond fund assets.

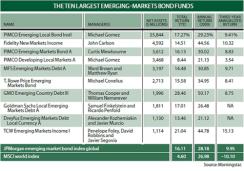

Investors have been well rewarded. Since the rally began in March 2009, local currency bonds in Indonesia and Brazil jumped 128 percent and 72 percent, respectively, through October 31, according to JPMorgan Chase & Co. Meanwhile, Argentina’s dollar-denominated sovereign bonds soared 224 percent. In the first ten months of 2010, the more-diversified 110 mutual funds in Morningstar’s emerging-markets bond universe climbed 15 percent, on average.

The rally isn’t overheated, says Keith Gardner, manager of Baltimore-based Legg Mason’s $649 million Western Asset Emerging Markets Debt Fund. Dollar-denominated sovereign bonds are trading at spreads with little room for more tightening, Gardner admits, but he still sees opportunity in local currency and corporate bonds.

Claire Husson-Citanna, co-manager of the $287 million Emerging Market Debt Opportunities Fund for San Mateo, California–based Franklin Templeton Investments, thinks too much short-term money may have again poured into emerging debt markets, with no regard for risks such as inflation or a stronger-than-expected rebound in the U.S. But Gardner maintains that the bulk of asset flows are there to stay. “It isn’t just hot money,” he says, noting that much of the cash is from sovereign wealth funds and low-turnover mutual funds.

This is hardly surprising given robust economic growth and the fact that most developing countries spent much of the past decade restructuring debt and enforcing prudent monetary and fiscal policies. As a result, they’ve become much stronger credits.

Another draw is the potential for local currency appreciation, driven by a weak U.S. dollar. Despite recent interventions, investors expect emerging-markets foreign exchange pressures to persist. And like local currency sovereign bonds, corporate bonds are still attractively valued. Sixty percent of the TCW Emerging Markets Income Fund’s assets are in corporate bonds, while the average emerging-markets debt fund has a 25 percent allocation. That difference largely explains the fund’s 21 percent year-to-date gain through October 31.

James Carlen, who co-manages Boston-based Columbia Management Investment Advisers’ $234 million Emerging Markets Bond Fund, is keen on Brazil’s real-denominated sovereign bonds, which he says have appealing carry characteristics. Carlen also likes Russian corporate bonds and Indonesian local currency sovereign bonds. Like Brazil, Indonesia, which is growing at more than 7 percent a year, benefits from a strong economy and global demand for its commodities.

Franklin Templeton’s Husson-Citanna favors emerging-markets bonds over the long haul, although she’s mindful of the short-term risks. A reversal of U.S. monetary policy would stun countries that borrowed heavily and cheaply on the global capital markets, she says. But precluding such an event, capital will keep flowing to emerging bond markets. “This is still a largely underinvested asset class,” says James Craige, manager of the $324 million Stone Harbor Emerging Markets Debt Fund.