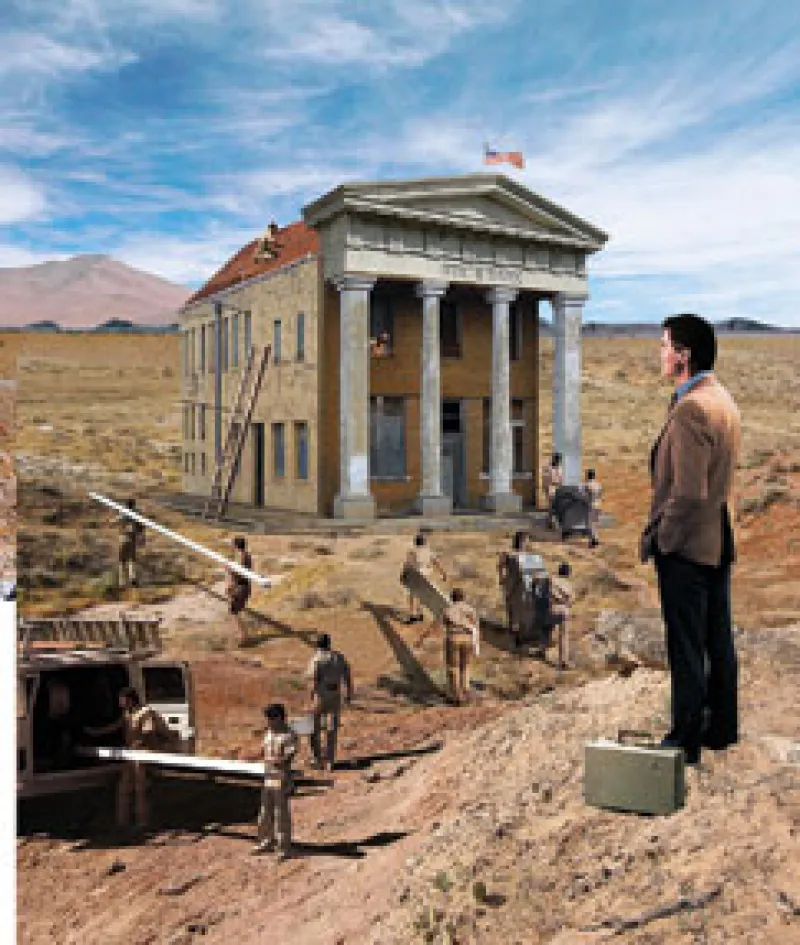

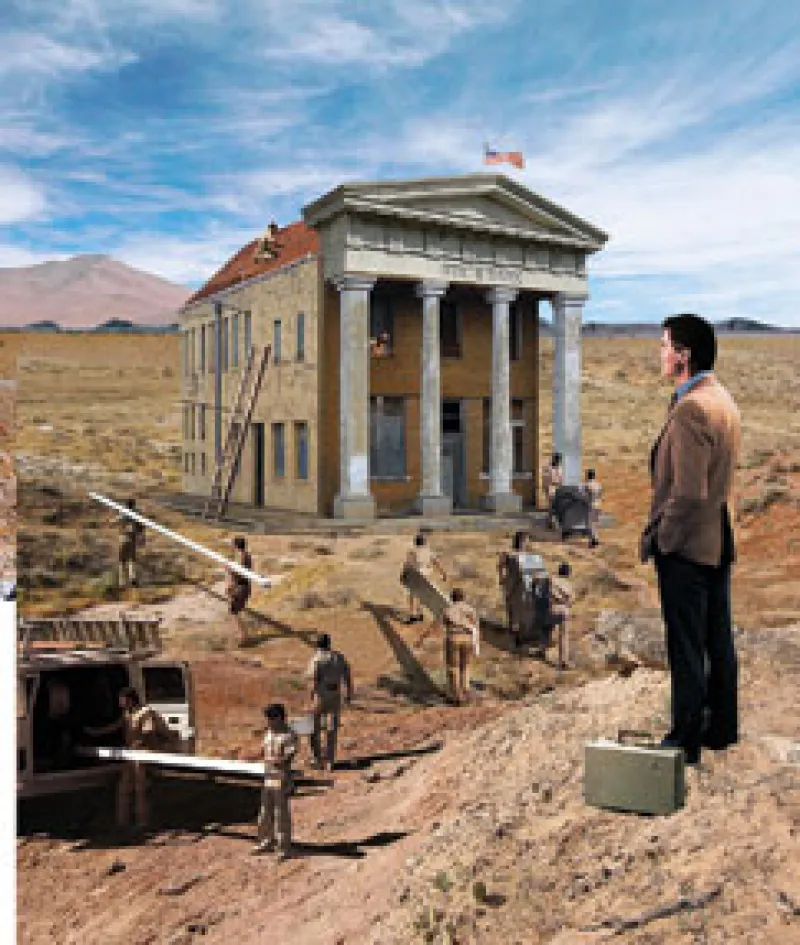

Entering a 'Contained Depression'

Forecaster David Levy anticipates an extended period of economic weakness, asset price deflation and credit market tightness.

David Levy

October 14, 2008