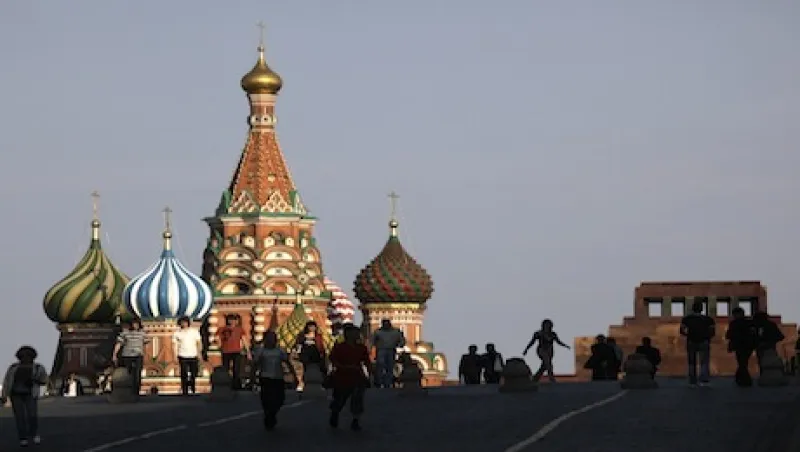

Pedestrians walk past St. Basil's Cathedral in Red Square in Moscow, Russia, on Monday, June 22, 2009. The ruble fell against the dollar and the central bank's target exchange-rate basket as stocks and oil prices declined. Photographer: Alexander Zemlianichenko Jr/Bloomberg News

ALEXANDER ZEMLIANICHENKO JR/BLOOMBERG NEWS