Seth Merrin recalls the day his charitable foundation opened a 144-acre youth village in a field in Africa. There was a long line of teenagers standing in the blazing sun holding small, brown paper bags.

The brown bags held “all their worldly possessions,” says Merrin, whose wife, Anne Heyman, founded the Agahozo-Shalom Youth Village in 2008. Next fall the village, near the Rwandan capital of Kigali, will graduate its first class. Many of the 125 students, who hail from all 30 districts of Rwanda, are orphans of the 1994 genocide and will soon bring the basics of running a business, employing modern agricultural and construction techniques, and personal finance skills back to their small villages.

The equity trading firm Liquidnet is a long way from Rwanda. But it is one of a growing list of financial firms in the West that are looking beyond the simple gesture of writing a check in favor of involving their entire staffs, their families and other companies in large, long-term projects that cross the globe. “Our most recent analysis of corporate giving trends make clear that leading companies, including those in financial services, increasingly are investing in programs that allow employees to bring their values to work—going beyond matching gift policies to include company-supported volunteer offerings and pro bono service projects,” the director of the Committee Encouraging Corporate Philanthropy, Margaret Croady, says.

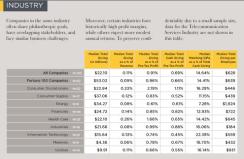

According to the CECP’s annual Giving in Numbers report, financial services companies as a group held their own this year, donating a median of 14 percent of their revenues, or $24.72 million, to a mix of causes: 24 percent of the total went to community and economic developments, 19 percent to K-12 education, 7 percent to cultural institutions, and 1 percent to the environment.

In recent years, the CECP has recognized, in addition to Liquidnet, the PNC Foundation’s Grow up Great education program in 2008, largely conducted by the bank’s employees; Charles Schwab, in 2009, for its Money Matters program, a joint initiative with the Boys & Girls Clubs to foster financial literacy; and Goldman Sachs, in 2011, for its 10,000 Women program, which fosters economic growth by educating women around the world with a model created for small businesses.

One organization that hasn’t sparked CECP’s radar yet is High Water Women, a group created by female hedge fund professionals. Leslie Rahl, founder and president of Capital Market Risk Advisors, a risk consultancy, and Kathleen Kelley, a portfolio manager at Kingdon Capital Management, started HWW in 2005 to encourage volunteerism among their peers, share their knowledge and help women advance in the financial world.

The organization hit its stride the same year that Muhammad Yunus of the Grameen Bank won the Nobel Prize. In fact, HWW met Yunus at a symposium during which he floated the idea of a “Bankers Without Borders” organization, according to HWW’s director and chairwoman emerita, Alexandra “Sandra” Poe. As a current board member recalls, those involved with HWW at the very beginning were as impressed by the microlending concept as anyone. It’s what Poe describes as the “romantic story of the woman who gets a goat and makes goat cheese.” But they weren’t convinced that such direct donations were the best use of the group’s expertise. As a senior partner for Reed Smith LLP, an international investment law firm, in the private funds practice working with hedge and private equity funds, Poe felt the major issues of microfinance were not widely understood or being addressed. More challenging, she felt, was “the organic transfer of funds from non-profit or NGO into a non-bank or financial institution and eventually a bank—and there are many other steps along the way that one could take.” These tougher junctures weren’t being widely covered.

Poe met with the Grameen Bank and suggested HWW start training women how to understand where the sector really needed their help and get them discussing those issues. And, says Poe, we asked that if we accomplished that “could we work with Grameen and go into the field?” To her surprise, Yunus asked HWW to create training program literature for Bankers Without Borders. That is how HWW came to write Microfinance 101 training for the Nobel Laureate, says Poe. BWB has now used that program to train more than 4,000 volunteers.

Today HWW is working on three Grameen projects in the field with a possible fourth on the horizon. The three are located in Pokuase, Ghana, where Dana Dakin, formerly of Goldman Sachs and founder of Women’s Trust (a partner of HWW) launched what became a bank; a Haiti-based program called Fonkoze, developed by Anne Hastings and the Grameen Foundation; and, in Colombia, South America, where HWW is preparing a Tier III microfinance risk analysis to allow a Grameen Foundation installation there to transform to its next stage. They’re a little short-staffed for the moment but with a large core group on the ground in Ghana. And some volunteers have had to pay air and other expenses from their own pockets. But Poe and the current board chairwoman, Eileen Mancera, are confident. Mancera is a managing director charged with business development for Morgan Creek Capital Management, who leads the HWW’s local New York City programs in financial literacy (originally created by Muriel Seibert herself), where demand is stronger than ever. Also, HWW just got three grants for the literacy program, all from the financial industry: MCCM, the Black Rock Foundation, and the NYSE-Euronext Foundation.