Buyback Scorecard The S&P 500

as Stock RepurchasersBest & Worst CompaniesIndustry ComparisonsThe biggest banks in the U.S. unveiled seven of the ten largest stock buybacks in the second quarter, led by a $10.6 billion program at New York–based JPMorgan Chase & Co. In total the major banks earmarked some $35.5 billion to trim share counts that had soared in the wake of the financial crisis, when they needed to issue stock to keep themselves afloat. The buyback rush came off as a kind of celebration — they had had to wait until after they passed the 2016 Federal Reserve stress tests in June to announce those programs. Certainly, it represented a long-withheld gesture toward shareholders.

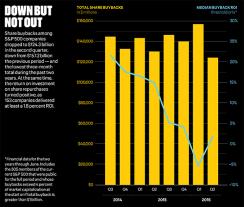

The banks are part of the second-quarter Institutional Investor Corporate Buyback Scorecard, which sees share repurchases reverse a long decline that began in 2014, with median buyback return on equity edging back into positive territory, if barely. A field of 305 Standard & Poor’s 500 companies post 1.8 percent in median buyback ROI, up from –5.3 percent in the first quarter.

Developed for Institutional Investor by New York corporate strategy consulting firm Fortuna Advisors using data from S&P’s Capital IQ unit, the scorecard has reported on stock buybacks since the first quarter of 2013. Each scorecard reflects eight quarters of buyback data, beginning in January 2011. Five and a half years of data underscore the inadequate returns and persistent bad timing in buybacks, notes Fortuna’s CEO and co-founder, Gregory Milano.

Buybacks may have recently edged back into the black, says Milano, but companies shouldn’t take a victory lap yet. Getting a mere 1.8 percent on any other corporate investment would be disappointing. To break even on share buybacks, Milano estimates, corporations would need to generate a minimum of 8 percent in ROI. Only 111 companies on the latest scorecard meet that hurdle; 194 fall short.

Past scorecards have exposed a tendency for lousy timing, as evidenced by a benchmark we call buyback effectiveness. Positive buyback effectiveness indicates that corporations have executed share repurchases ahead of price increases; in short, the repurchased shares are worth more after the company buys them back. Conversely, negative buyback effectiveness suggests that the repurchased shares promptly fell in price.

Armed with presumably excellent inside information about their own activities, only 120 of 305 companies managed to execute buybacks that have exceeded or kept pace with total shareholder returns. All others trail underlying total ROI. In fact, half of the ten companies on the scorecard that announced the biggest buyback programs in the second quarter reveal negative buyback returns.

JPMorgan Chase isn’t one of them. The big bank posts a lackluster 4.9 percent in buyback ROI but still beats median buyback ROI for the Banks sector by 8.9 percentage points and median buyback ROI for all scorecard companies by more than 3 percentage points. Better yet, its buyback ROI edges past underlying ROI, evidence that it effectively timed repurchases before the shares rose in value.

With the Fed’s okay, JPMorgan chair and CEO Jamie Dimon unveiled buybacks beyond the $6.4 billion authorized last year. The current program equals about five months of the bank’s net income in 2015.

Citigroup too found itself with ample cash and a desire to please shareholders. The New York bank also basked in the glow of a passing grade from the Fed — some previous stress tests had not gone well. Citi promptly declared an $8.6 billion buyback on June 29. Still, if buybacks required a financial-health advisory, Citi might have hesitated to pursue a repurchase program. Two years of previous Citi buybacks had pummeled shareholder value, producing a –16.5 percent return. Such a subpar performance for other investments of similar scale would stir up a mob of shareholders wielding pitchforks.

Where had Citi gone wrong? Buyback effectiveness had been anything but timely. As buyback ROI sank, total shareholder return, or buyback strategy, slid 4 percent. The gap between buyback ROI and total shareholder return suggests that Citi repeatedly bought shares ahead of price declines.

Regardless of past performance, Citi CEO Michael Corbat unveiled the new buybacks enthusiastically. He insisted they were the right move and promised returns “that our shareholders expect and deserve.”

In Citi’s defense, rock-bottom interest rates have burdened the banks with low net interest margins. And shareholders seem to crave the short-term bump of buybacks, no matter how ineffective they are as investments. With historically low rates squeezing banks, online investment club Action Alerts Plus portfolio manager (and TV stock guru) Jim Cramer and director of research Jack Mohr have described buybacks as “the only way to create much of an impact on share price.”

Morgan Stanley CEO James Gorman announced $3.5 billion in buybacks in late June, singling out return of capital as the key metric of the firm’s strategic plan, despite two-year ROI of –22.6 percent, the worst buyback ROI of the ten largest second-quarter buyback announcements.

In the third quarter larger buyback announcements kept coming, knocking three other banks — Bank of New York Mellon Corp., U.S. Bancorp and Capital One — from the ten-largest buyback list. Foster City, California–based credit card giant Visa and Cambridge, Massachusetts–based biotech Biogen each unveiled $5 billion buybacks. Rupert Murdoch’s New York–based media company 21st Century Fox set a $3 billion target. These companies have also suffered sketchy buyback records, however. Earlier Biogen and 21st Century Fox buybacks had negative returns.

Other companies fare better. Morris Plains, New Jersey, industrial conglomerate Honeywell International can make the best case for $5 billion in buybacks. Investing in its own stock produced a return of 19.6 percent, a gain bigger than that of the underlying shares by 5.7 percentage points. Visa posts 18 percent in buyback ROI but still lags total shareholder return by 4.3 percentage points.

Time will tell whether the recent uptick in buyback ROI signals a trend or just a breather before further declines. Some companies and industries chalk up better results, but buyback ROI still trails total shareholder return.

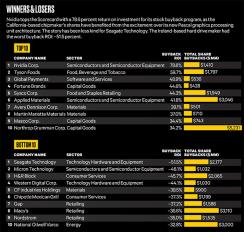

Buybacks are a feast or famine business. The ten companies at the top of the current scorecard post a median 43.1 percent in buyback ROI, whereas the ten at the bottom post a median of –38.4 percent — a whopping differential. Laurels are welcome for the winners, but laggards invite scrutiny by shareholders.

For example, robust demand for video gaming moves Santa Clara, California, chipmaker Nvidia Corp. into first place overall in the second-quarter ranking. Bank of America Merrill Lynch analysts credit Nvidia’s commanding 90 percent market share in graphics processing unit chips for the electronic gaming market. As a result, Nvidia scores 78.6 percent in buyback ROI, significantly better than its total shareholder return, thanks to timely execution.

Nearly 60 percent in buyback ROI propels chicken and pork giant Tyson Foods, headquartered in Springdale, Arkansas, to first among its Food, Beverage and Tobacco peers and second place overall. Helped by Tyson, the sector posts a top-drawer 12.3 percent in buyback ROI. Despite thin margins and vulnerability to commodities markets, Tyson capitalized on demand for meat products that cater to a growing global appetite for protein. Shares rose as timely buybacks fueled buyback ROI.

Sysco Corp., the Houston-based food distributor, garners fifth place. It generated 44.3 percent in buyback ROI as earnings and earnings per share slid by 15.1 percent and 10.3 percent, respectively.

Sysco chief financial officer Joel Grade makes a strong case for the buybacks, built on 38 percent growth in free cash flow in fiscal 2016 to $1.4 billion. “We plan to continue our announced $3 billion share repurchase in fiscal year 2017,” says Grade.

Sysco’s buyback ROI got a recent lift from accelerated share repurchases, launched after the collapse of a proposed merger with Rosemont, Illinois–based US Foods. The company spent nearly $2 billion on buybacks over eight quarters, through June, including 2.4 million shares retired in the first half of calendar 2016. As of late August, shares since January had risen by 33 percent.

Securities and Exchange Commission filings report that Sysco was prepared to proceed with buybacks even as a potential default loomed because of problems with a planned acquisition of the Brakes Group, a U.K. food wholesaler. The resulting delay threatened to leave Sysco short of the cash required to redeem notes due in 2019 and 2021. Sysco succeeded in closing the Brakes deal ahead of its deadline, erasing the default warning, but analysts still question the quality of earnings muddied by serial restructurings and share repurchases. “The charges and add-backs have helped to mask weakness in GAAP [generally accepted accounting principles] earnings,” notes analyst Ajay Jain of Pivotal Research Group.

One sector confronting significant headwinds — Technology Hardware and Equipment — produced –5.8 percent buyback ROI. Dublin-based data storage developer Seagate Technology fares worse than other companies in that sector. At No. 305, Seagate is also dead last on the quarterly scorecard, with its buyback investments losing 51.5 percent over two years through June 2016. By contrast, if investors had simply held Seagate shares, they would have lost less than 30 percent.

So far, Seagate hasn’t really been punished for poorly timed buybacks. In the May conference call, share repurchases drew no criticism or questions from analysts.

Likewise, Boise, Idaho–based chipmaker Micron Technology, which comes in second from the last on the quarterly scorecard, trails its peers in Semiconductors and Semiconductor Equipment, a sector that ekes out 0.1 percent in buyback ROI. Micron saw 46.1 percent of its investment in buybacks go down the drain, much of it from poor timing.

Seagate, Micron and other companies cannot turn back the clock on lackluster or languishing buyback programs, although many shareholders continue to ignore the problem. Truth in advertising, however, would demand more candor when corporations sink billions of dollars — some from free cash flow, some from debt — into stock buybacks. Many might see higher returns by investing instead in what many claim are their most valuable assets: people and technology.