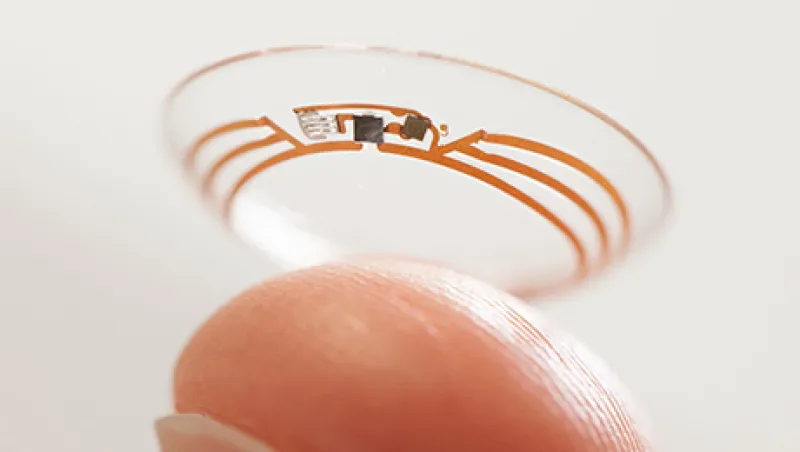

Tech Firms Take Bigger Steps into Health Care

Apple, Google, Uber and others are recognizing the growing opportunities in the changing health sector, but regulatory worries hold back some innovation.

Kaitlin Ugolik

January 6, 2016