Every asset price cycle is different, but they all end the same way: in tears. As obvious as this truth is to investors, when the sad end to the credit cycle arrives, it always comes as a big surprise to many — including the central bankers who, reliant on their models, confidently tell you that no recession is (ever) in the forecast. But successful long-term investing is predicated on knowing not just where the happening parties are during the reflationary parts of the cycle but also, even more important, when the time has come to leave the dance floor. In our view at TCW, that time has already come.

Consider chart 1, which shows the trajectory of cumulative asset prices (stocks, bonds, real estate) against that of aggregate income (GDP):

Over the course of the past 25 years, the traditional business cycle has been replaced with an asset price cycle. Rather than let recessions run their painful but necessary course, central bankers have moved to dispense the monetary morphine. The Fed’s playbook on this is well worn. First, policy rates are lowered. This triggers a daisy chain of events. Low or zero rates promote a reach for yield. The reach for yield lowers capitalization rates across a variety of asset classes, which in turn spur a rise in asset prices. Rising asset prices — the so-called wealth effect — apparently rescue the economy by rebuilding balance sheets and restoring the animal spirits. And voilà! Aggregate demand rises, businesses invest, and a virtuous growth process is launched.

Well, maybe not so much. If it were all so simple, then why is it that after 90-something months of zero or near-zero rates, growth is sputtering, the corporate sector is in an earnings recession, and productivity growth is negative?

The explanation is simple: Growth is not a simple function of higher asset prices. Growth results when productive sectors of the economy make themselves more productive by delivering goods more efficiently or by developing innovative products valued in the marketplace. In short, the vast partnership of labor and capital that is our economy must constantly up its game so as to expand output and, along with it, incomes. The process by which this happens is essentially Schumpeterian: Profitable activities expand and bid resources away from the decaying and inefficient. Say what one wants, this has been the wealth engine for centuries.

The central banker’s model of growth not only ignores what Schumpeter called creative and destructive forces; it is antithetical to them. What does a boom in asset prices actually foster? An elevation in asset prices means that an economy has more assets. If one doubles the value of all homes in the nation, then one would have twice as much real estate. But twice the real estate means there is twice the real estate to lend against. Effectively, higher asset prices are the Fed’s mechanism for expanding the systemwide pool of loanable collateral. More collateral means that more credit can be created. In the short run, more credit creation feels like an economic recovery, which is why monetary expediency has so many cheerleaders.

But buying growth today with credit that needs to be repaid tomorrow is not a free lunch! Artificially stimulated credit creation means that marginal or even unprofitable enterprises are being fed when they should actually be starved. Further, the low-rate-induced asset price inflation preferentially directs credit to those who are already asset rich. Those whose assets have inflated now possess more collateral, making them more creditworthy in the eyes of the lender. This results in all sorts of distortions that serve to further impair efficiency. Fortune 500 companies get to borrow at low cost so as to repurchase shares, even as small businesses are starved for capital. Affluent homeowners get favorable access to loans to build swimming pools, whereas renters suffer impoverishment by the resulting housing price inflation.

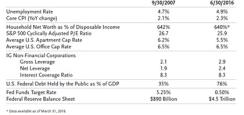

The long-term consequences of policies that fixate on credit growth lead to a general, systemwide expansion of leverage ratios. Meanwhile, this credit inflation takes power away from the market-based mechanisms that would otherwise allocate resources to their optimum uses. The result? Leverage goes up faster than the income available to service it. As such, the credit-fueled expansion inevitably comes to a bad end. We’ve lived this story before: Indeed, whereas every cycle is distinctly different, they all end up suffering from the same central banker–induced maladies. Consider the similarities in terms of where we are today and where we were in 2007 (see chart 2):

It’s back to the future — again. Leverage has returned, most notably in the corporate sector, in which debt metrics have not just round-tripped but indeed are now in excess of the levels experienced before the late-2000s financial crisis. And although the Fed clings to the fiction that it is data dependent, its response function reveals monetary policy to be what it really is: a put on financial prices. But can the members of the Federal Open Market Committee hold back the future tides of deleveraging? No, though we expect that they, like their comrades at the European Central Bank and Bank of Japan, will keep trying.

Negative rates can be best understood as merely the latest attempt to forestall the failures of policies past. But is anyone helped by establishing negative hurdle rates to incentivize investment? If a commitment of capital requires a negative opportunity cost, then whatever activity that might be launched will assuredly be productivity-destroying. Negative rates have all the economic logic of destroying the village so as to rebuild it. It is monetary madness, and although it might hold back the flood for a time, it fairly well guarantees that when the flood comes, it will be worse than it would otherwise have been.

Face it: The central banking emperors have no clothes. But might the Fed come up with new artifices to prop up the towers of leverage it has built? It might, though that would be folly. Yet underestimating folly is, we suppose, a folly of its own. The Fed could continue to use its printing press to falsify capital market signals — but to what end? When a central bank buys an asset with an electronically printed dollar, a something-for-nothing trade has taken place. Unless everything we understand about economics is plain wrong, the Fed cannot go on blithely adding printing press dollars to the system and expect no ill effects. Essentially, inflationist monetary policies cannot be the answer to the problems caused by inflationist monetary policy.

And this is precisely our point. When the supposed solutions to the Fed’s dilemma are merely new problems, you know you are approaching the cycle’s end. Our counsel remains as it has been: Avoid those assets that will be broken in the coming deleveraging while keeping a steady-as-she-goes attitude toward the future purchase of those assets that will merely bend when the bust comes.

Tad Rivelle is chief investment officer for fixed income at TCW in Los Angeles.

Get more on macro.