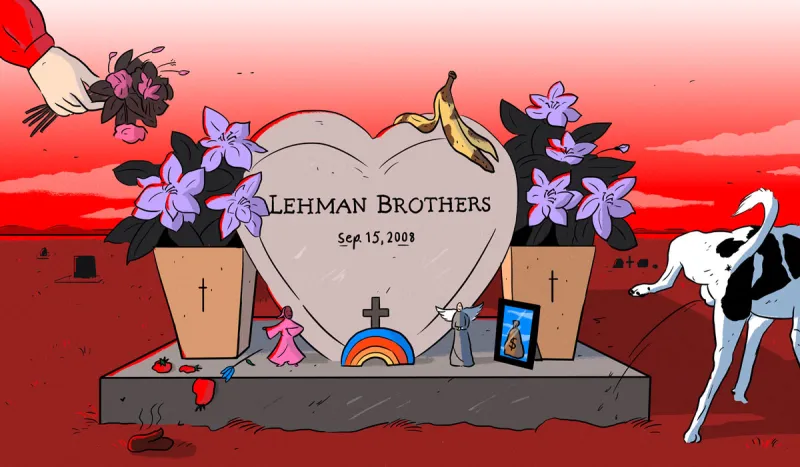

The Worst Takes on the Financial Crisis

Illustration by Laura Breiling

Because the world — and your inbox — do not need another article called “Ten Years on: Lessons From the Financial Crisis”

Timothy Geithner

Business Insider

Albert Edwards

Joe Ciolli

Mark Spitznagel