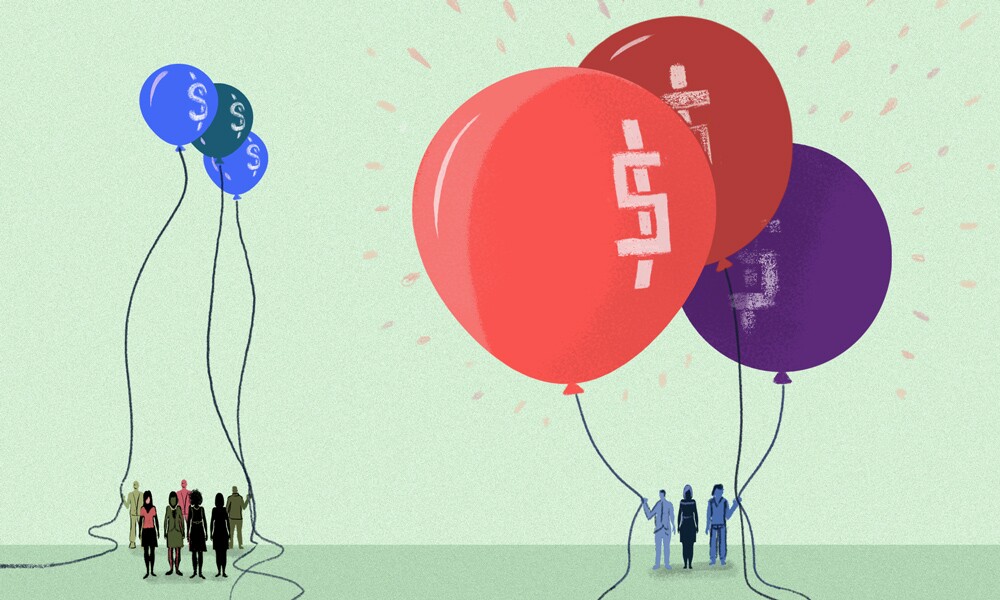

Judging by revenue and organic growth, the gap between the best and the worst asset managers is widening.

In 2017, managers in the top quartile grew revenue by 21 percent versus just 2 percent expansion for those in the bottom. This spread was five percentage points greater than in 2016, according to McKinsey & Co.’s annual review of the North American asset management industry, published today. A year earlier, top managers grew revenue by 5 percent, while fourth-quartile firms shrunk by 9 percent. Their ability to capture new money proved an even starker divide.

“Amid the positive economic and markets picture, firms pulled apart in organic growth, the most important metric, which we think of as a firm’s ability to take on new money regardless of market conditions,” said Ju-Hon Kwek — a McKinsey partner and an author of the report — in an interview with Institutional Investor.

McKinsey defines performance in terms of growth and profitability using data from 100 managers, which together represent 80 percent of the industry’s assets under management.

“In what should have been an exceptional year for nearly every firm, the gap between over- and under-performers widened in significant ways,” the report stated. “In particular, scale emerged as a far more important gauge of growth and profitability than in any year prior.”

[II Deep Dive: McKinsey: Asset Management’s Problems Are Here to Stay]

Since 2014, according to McKinsey, top-quartile firms have increased margins to 52 percent from 48 percent. Margins at bottom-quartile firms have in turn declined from 13 percent to 11 percent. Top firms reaped net inflows of 9 percent, a little below levels of two years before. Net asset flows at bottom-quartile firms were negative 13 percent, worse than the 9 percent outflow of 2015.

Firms excelling in this environment tend to be behemoths — with $1 trillion-plus — or boutiques managing $50 billion or less. “The firms that fared poorly in 2017’s benign environment were clustered in the middle,” the report noted. “These managers, typically with a broad range of products and capabilities spread over several hundred billion dollars of AUM, were overrepresented in the category of firms with negative flows.”

The year was overall a good one for the industry. Global assets under management grew 11 percent, reaching a record $88.5 trillion. Rising market values drove asset managers’ good fortunes, and aggregate profitability rose from 30 percent in 2016 to 33 percent last year.

But these shiny growth figures belie some worrying fundamentals, according to Kwek. “Even though it was a time of plenty, there were broad-based trends underpinning a market of haves and have-nots. Institutional clients want to work with fewer managers, and retail clients are becoming more concentrated in their buying patterns,” he said. “We’re moving from a world where there were 300,000 advisors making independent decisions to a smaller number of people at the home office controlling how products get distributed.”

For example, organic growth contributed less than 30 percent of the new profits that traditional asset managers made in 2017. Rising costs ate up $4.5 billion of profit gains and investors’ broad shift to low-fee asset classes vaporized $1 billion. Fee compression also reduced profits by $200 million, and total fees paid by end investors have fallen by an average of 27 percent.

“To be sure, the past eight years have been a great time to be a client of the asset management industry,” the report said.