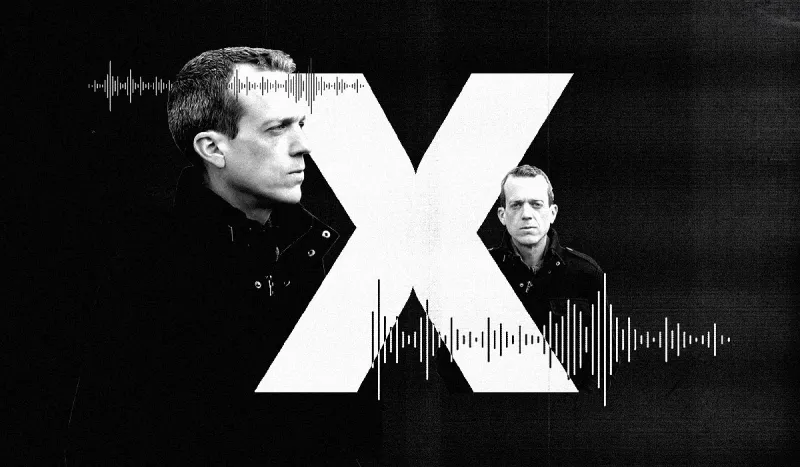

Tom Hardin.

(Illustration by II / courtesy photo)

Tom Hardin knew he had crossed a moral line when he found himself standing on the corner of 41st Street and Lexington Avenue in Manhattan, holding an envelope stuffed with $10,000 in cash.

Hardin, who grew up in a comfortably middle-class family in suburban Atlanta and had attended the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business as an undergraduate, was a junior partner at a small hedge fund that had prestigious ties to Tiger Management founder Julian Robertson Jr. At age 29, Hardin had a wife, a promising and lucrative career, and plenty of ambition.

Until that spring day in Manhattan in 2007, the idea that there was something wrong with the insider trades Hardin had done had seemed abstract to him; it had barely even registered that they weren’t exactly legal. But as he nervously handed the envelope to an analyst from Moody’s — the one who had tipped off a contact of Hardin’s that private equity firm Hellman & Friedman was about to acquire software company Kronos, information that Hardin and others traded on illegally for a profit — it began to sink in that he might be in over his head.

When the analyst asked, “Are you Tom?” Hardin, who had never met the man, passed him the envelope without looking at him. “I was like, ‘Holy shit . . . . If God sees this, obviously this is not a gray area.’”

That heart-stopping episode wasn’t the last for Hardin. Later assigned by his contact to deliver a big payment to a tipster in California, Hardin went to LaGuardia Airport with a carry-on bag full of cash and was about to board his flight when he was randomly stopped at the gate by two agents for the Transportation Security Administration.

“They took my carry-on and I thought, ‘Oh my God, these guys must know what I’m doing,’” says Hardin. Amazingly, the agents took note of the contents of the bag but simply handed it back to him. “They said, ‘Have a nice flight,’” says Hardin.

The woman who had assigned Hardin the job of bagman turned out to be Roomy Khan, the Silicon Valley analyst who became “Tipper A,” a convicted insider trader who turned on many of the people in her network. They included Raj Rajaratnam, the co-founder of hedge fund Galleon Group who was arrested in a massive insider trading sting in 2009 and is serving an 11-year prison term, at the time the longest ever handed down for that crime. Khan served a year in prison for insider trading.

Unbeknownst to Khan, Hardin would eventually become “Tipper X” — the linchpin of and most productive cooperating witness for “Operation Perfect Hedge,” the U.S. government’s unprecedented crackdown on insider trading that resulted in some 80 convictions.

Over the past few years, some of those caught up in the sting who went to prison have completed their sentences and are starting to tell their stories.

For his trouble, Hardin, who pleaded guilty to insider trading in 2009, avoided that fate. But with a felony conviction on his rap sheet, he has found it just as hard to have a career as his fellow ex-cons who did hard time. A fateful phone call from the FBI — this one in 2016 — led Hardin to his first speaking engagement, telling a room full of rookie FBI agents how he crossed legal lines and rationalized his actions to himself at the time.

One of the agents told him he should consider talking to financial services firms. Hardin took the advice and eventually launched Tipper X Advisors, a speaking and consulting business where he counsels financial firms and their employees on the perils of poor decision-making, the slippery slope of rationalizations that can lead to unethical or even illegal behavior, and the importance of having a strong culture of compliance.

But before he could become an adviser to the FBI, he had to help them. Which is how, in 2008, Hardin found himself wearing a wire.

The similarities very much end there.

In contrast to the ultrarich Axelrod — or even the real-life Rajaratnam, a famously libertine billionaire who lived large until the feds came calling — Hardin is hardly a slick high-flyer. The khaki-wearing suburban dad ultimately netted just $46,000 from the trades that destroyed his career.

Hardin got connected to the technology analyst circuit in the early 2000s through a job covering tech stocks at a hedge fund in Greenwich, Connecticut. As is typical for tech analysts, Hardin made several trips to Silicon Valley and Asia, becoming a regular on the conference circuit, eventually meeting Khan.

By 2006, Hardin realized that in certain circles, insider trading was so rampant that it was virtually considered normal. Several hedge funds started hiring former employees of tech companies as analysts, in the hopes that they could call up their former co-workers and solicit tips. Hardin felt far removed from the scene at the time. He was doing his own research, he says, and didn’t have connections to the C-suite at tech firms anyway.

As he learned, this was a mark against him at the time. When he applied for jobs at hedge funds, he was competing with former tech workers. A frequent interview question was, “Tom, what’s your edge? What can you bring me that nobody else knows?” A would-be investor in the Tiger Seed fund where he eventually worked, Lanexa Global Management, even asked Hardin and his partner why he should take the “career risk” of investing in a startup when he already had a well-performing tech hedge fund in his portfolio: Rajaratnam’s Galleon Group.

Still, Hardin resisted the temptation and career pressure to trade on illegal information.

Until, one day, he didn’t.

When he got the tip about Kronos, he initially sat on it. But then he talked to a contact at a proprietary trading firm, a man with whom Hardin exchanged ideas a couple of times a month. The trader was losing money and was pressuring Hardin for ideas. At this point, Hardin’s thought process began to change. He finally had information that could actually pay off, and everyone knew that much bigger players, namely Rajaratnam, were doing it. And besides, who would he actually be hurting?

“It’s what you always hear with insider trading: Who’s the victim of just buying a stock before everybody else? It’s not like a Ponzi scheme, where I took your life savings,” says Hardin, who has since done a deep dive into the psychological aspects of what drives people to cross these lines and calls such rationalization “poor self-talk.”

“It’s not an excuse, it’s just the thought process,” he explains. “I could still actually think of myself as a good person and do this.” What’s more, Hardin says, he even got an endorphin rush.

Hardin says he was able to make his illegal trades without his partner’s knowledge. (Lanexa stayed in business for several more years and now operates under the name Peak Ten Management, according to SEC filings.) That’s because the firm’s trading guidelines allowed him to make a trade without clearance from the fund manager as long as it was less than 1 percent of the total portfolio. He sized these trades at 0.9 percent — small enough that he used their size as further justification that he wasn’t doing any real harm to anyone.

Hardin ended up getting four tips from Khan in 2007, illegally trading on all of them. But one in particular — Blackstone Group’s takeover of Hilton Hotels Corp. — landed him on the government’s radar. In hindsight, it seems obvious why: To regulators, it didn’t make sense that a high proportion of tech-focused analysts would be putting on big trades in the stock of a hotel chain. He says he put on his last illegal trade in September 2007.

At the end of that year, “Khan called me out of breath, saying, ‘Oh my God, the SEC is contacting me about the Hilton trade. I’m going to tell them I bought Hilton because Paris Hilton was in the news,’” says Hardin. “I thought, ‘That’s an awful excuse. You don’t tell the SEC that.’”

Hardin had devised a better one, in his view. Over the years he’d met a few people who’d been questioned by the SEC over legitimate trades around earnings announcements that turned out to be profitable. He figured that if he got a call from the agency about any of his illegal trades, he would simply explain that he speculated like this frequently and provide a list of losing trades that were similar.

“I had a plan in place in case the SEC were to contact me,” he explains. “But like Mike Tyson says, ‘Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.’”

On the morning of July 8, 2008, Hardin had just dropped off his dry cleaning in Manhattan’s Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood. He was about to hail a cab to work when FBI agent David Makol and another agent approached him on the street.

The agents explained that they knew about his four illegal trades and that he’d just been to Atlanta, where he’d been visiting a nephew, to show they had been tracking him.

Hardin’s reaction proved he was hardly a smooth criminal. “I immediately started making implicating statements about these cash payoffs, and I don’t even know if they knew about this stuff,” he says. “They were writing it all down.”

The agents produced a chart showing what appeared to be an elaborate network of names, which were whited out. The web led up to two big names at the top. Hardin figured, correctly, that one of them was Rajaratnam. An agent told Hardin he could help them build bigger cases, which would in turn help him out.

Hardin, badly shaken, took the agent’s card, told him he’d need to think about it, and went to work. On his lunch break, he went to St. Patrick’s Cathedral and gave his first confession in years. The priest told Hardin it sounded as if he had done the right thing 99 percent of his life, but really screwed up the other 1 percent. The choices he would make from that point on would define who he would be for the rest of his life, the priest told him.

Hardin took the priest’s advice to heart and decided to cooperate. The soft-spoken, self-described introvert admits it never occurred to him to get a lawyer at that time. Instead, he just did what the FBI told him. He wore a wire — a recording device about the size of a BlackBerry battery, which he kept in his shirt pocket — and secretly recorded people making implicating statements. This went on for nearly two years.

As a cooperator, Hardin had an unusual mandate. He was allowed to bring in anyone who was a person of interest, wherever they were based, including Silicon Valley. The agency was looking for people to talk about illegal trades they had made or about corrupt contacts they had inside tech companies. Hardin started by making a list of who he felt were the most corrupt people in the industry.

Some were people he wasn’t yet close to, so he had to build relationships to get them to talk. His cover was that he was a young analyst who was trying to build up contacts inside these tech companies and wanted to emulate their careers; he was hoping to play to their egos. It didn’t come naturally to him.

“When I was first starting speaking to people, I was terrible,” he says. “I’m supposed to ask a pointed question and then wait for you to respond, whether it takes you a minute or two minutes. I’m not supposed to fill the silence. But if I ask you that question, you’re looking at me weird. I’m thinking, ‘You must think I’m wearing a wire.’ So I’d fill the silence, just change the subject. And then the FBI would listen to it later. And they’re just like, ‘You have to stop filling the silence.’ They were sort of hard on me at first.”

With coaching, Hardin eventually got good at coaxing information out of people. But one encounter rattled him. It was with the manager of a small hedge fund, who exchanged information with Hardin once a quarter or so. Hardin had had roughly a dozen conversations with the man, but he never said much, and Hardin got the impression that the man might be suspicious of him. Then, out of nowhere, the man invited him to Sunday dinner at his home in Connecticut to discuss something. Hardin told the FBI agents, who excitedly met him at Grand Central and set him up with a wire.

The man picked Hardin up at the train station. “Tom, good to see you,” he told Hardin. “I brought swim trunks for you. We’re going swimming at my mother’s house.” They drove to an old mansion, where the man started to change into his swimming trunks in front of Hardin.

“He starts disrobing in this room, so he wants to see if something is taped to my chest,” Hardin says. “He’d probably talked to a lawyer who said, ‘Sounds like that guy’s wearing a wire. See if you can prove it.’”

Hardin had just watched an episode of The Sopranos, the HBO series about life in the mafia, in which a central character was murdered.

“My heart was pounding. I’m like, ‘I’m not getting undressed in front of you. I’m going to go to the restroom and do it.’ So I excused myself and I took the wire out and put it in my jeans and put these swim trunks on.”

They walked outside. Hardin remembers that it was eerily quiet. He also remembers the shovel, propped up against the house, next to a hole in the ground.

“I’m thinking, ‘Oh my God, is this guy going to try to kill me or something?’” Hardin recalls, that Sopranos episode fresh in his mind.

They went into the pool, where the man grabbed a tennis ball and engaged Hardin in an awkward game of catch. After a couple of minutes, the man finally confessed that he thought Hardin had been acting strange. “I have one question for you,” the man said. “Have you been approached by the SEC? I need to know.” Hardin said no — a technically honest answer. The man opened up, answering some of the questions Hardin had been asking him about inside information. But none of it was caught on tape. The man, whom Hardin declines to name, is managing money to this day.

At this point, Hardin’s connection to the investigation had not yet been publicly revealed. But in May 2009, the FBI told Hardin he should probably get a lawyer. Still, he wasn’t outed as Tipper X until early 2010.

“This idea of, ‘Who am I hurting? It’s a victimless crime,’ just starts to unravel” when that happens, Hardin says. “It touches a lot of people.”

Due to repeated delays, his sentencing got pushed back until 2015. Hardin had moved to the suburbs and started a family by that time, but with a felony conviction he found it impossible to restart his career. He became depressed, and his weight ballooned to 215 pounds. A stern warning from a doctor pushed him to take up running, which became a kind of therapy.

After his wife signed him up for a 5K, he kept at it, eventually running marathons and then ultramarathons. He filled his days by taking care of his kids, volunteering, and making extra cash through what he calls retail arbitrage, buying products on sale at drugstores and reselling them online.

Then, in August 2016, he got the FBI speaking gig. He took it seriously, explaining how someone in his situation feels and how it’s important to gauge a target’s mental state, reminding them that some accused insider traders — such as Visium Asset Management’s Sanjay Valvani — have committed suicide after being caught.

“It was really eye-opening for these young agents to hear the story from my side,” Hardin says. “They felt like my life must be going well, because I helped them so much. No, actually, I’m a convicted felon. I just found out that I couldn’t coach my daughter in soccer because of the felony.”

A few of the agents told him they felt others in the industry would benefit from his story. Hardin found that speakers’ bureaus wouldn’t work with him because of his felony conviction, so he built a list of hedge funds from scratch and sent out blind pitches. Of several hundred initial emails, one resulted in a speaking gig, but it was enough to get more gigs via word of mouth. Since then he has told his story to more than 150 audiences, including 90 hedge fund firms.

He acknowledges that he’s not exactly a motivational speaker.

“I’m not like somebody who had some crazy life event that just happened to them, and they overcame it. It was all self-inflicted. I call it ‘overcoming self-inflicted career decimation,’ which is a smaller niche,” he says dryly.

But he’s grateful: his marriage survived; his children are healthy. And while he can never work as a trader again, he is finding some satisfaction in offering advice to young traders on how not to end up like him.

Whether it’s being heard by the people who need to hear it most is unclear.

“It’s interesting — the hedge funds bringing me in all have great cultures of compliance,” he says. “The ones where I know I should be going are never going to have me in.”