Illustration by Yarek Waszul

“Tax reform has delivered for workers!”

So proclaims a recent editorial in The Wall Street Journal by Gary Cohn, former director of the National Economic Council under President Donald Trump. The onetime Goldman Sachs senior executive mounts a vigorous defense of the 2017 tax bill, calling it a victory for supply-side economics and for the American people.

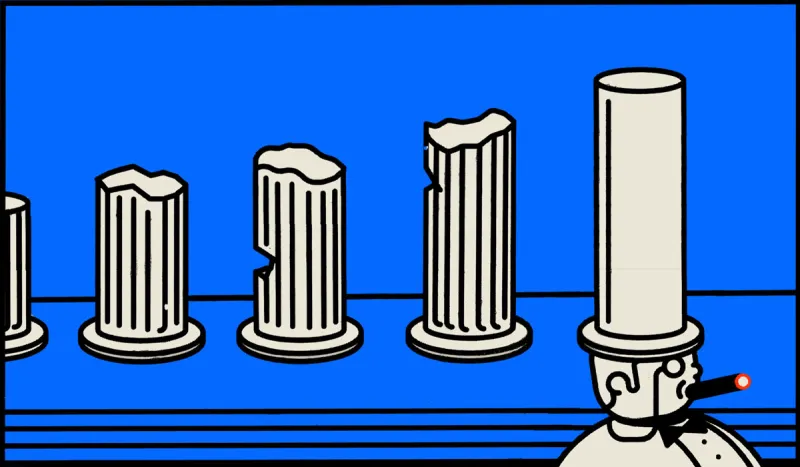

In the past decade the gap between income growth for ordinary Americans and that for their wealthiest countrymen has widened at a rate unseen since the Gilded Age. As a result, populists now openly challenge neoliberalism from both the left and the right. Talk of tax cuts and trickle-down effects by financial elites is a rearguard action fought on behalf of a crumbling economic consensus. Like the delusional Vietnam War–era generals who pointed to rising body counts as progress toward victory, Mr. Cohn, President Trump, and others frequently refer to a soaring stock market and low unemployment as indicators of a “surging economy.”

At this point many of us understand that beneath the hood, the once powerful American engine of mass prosperity is malfunctioning. When 10 percent of the American population owns 80 percent of equities, a 35 percent gain in the Nasdaq is a vanity metric rather than a true indicator of system performance. Similarly, low unemployment rates mask the neo-serfdom of the sharing economy — and thus tell only part of the story.

The Stadium of Franklin Delano Roosevelt stood on a New Deal consensus from the mid-1930s until well into the 1970s. Policymakers in both parties sought to limit the concentration of economic power, decentralize the corporate sector, and ensure free and fair competition for small business. In the mid-1970s, American politicians abandoned this accord for the Stadium of Ronald Reagan, where subservience to the free market and an abiding skepticism of government became shibboleths in both parties. It may have been Reagan who convinced Americans that their government was out to get them, but it was a Democratic president from rural Arkansas who gutted the federal bureaucracy in the mid-1990s and then used his State of the Union address to brag about it.

The one thing — perhaps the only thing — that the left and the right seem to agree on today is that the current field of play no longer seems so prosperous for the average citizen.

Following leaders like Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren on one team and Marco Rubio and Josh Hawley on the other, people are looking for the exits. Where they will go is unknown, but whether closure comes in 2020 or a few years later, the lights are flickering in the House that Ronnie Built.

Matt Stoller’s Goliath: The 100-Year War Between Monopoly Power and Democracy is a timely guide for those looking to understand how, where, and by whom the next stadium will be built. Goliath’s central assertion is that to understand why our economy distributes its fruits so unevenly, you must recognize what many elites and policymakers struggle to see: The present-day prevalence of monopolies and other significant concentrations of economic power is unprecedented in American history.

His time on Capitol Hill during the financial crisis propelled Stoller into a decade-long exploration of American economic history. In Goliath he unearths a century’s worth of antitrust debates to show the consequences of monopolization and economic concentration. For decades, American antitrust battles were led by a seemingly forgotten assemblage of anti-monopolists that includes John Sherman, Louis Brandeis, and America’s most famous class traitor, Franklin Roosevelt.

The book’s unlikely hero, however, is Congressman Wright Patman, the son of an East Texas tenant cotton farmer. The populist Patman’s 46-year career in the House of Representatives, launched on the eve of the Great Depression, mirrors the rise and fall of the New Deal economy. Patman was instrumental in passing the Bonus Bill for World War I veterans; he also led impeachment proceedings against then–Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon. He was, as one eulogizer said, a man who “comforted the afflicted and afflicted the comfortable.”

In 1975 a group of newly elected Democrats known as the “Watergate Babies” deposed the elderly Patman as chairman of the House Financial Services Committee. That Patman’s ouster came neither at the hands of Republicans nor at those of his enemies on Wall Street is a central point in Goliath: In their zeal to end the Vietnam War and enact civil rights legislation, Democratic legislators ceded thought leadership on matters of political economy to a rising technocratic elite. Patman — elderly, white, and Southern — fell victim to the grandfathers of today’s woke capitalists.

A credentialed technocracy soon led the Democratic party astray. Well-intentioned, corporatist liberals undermined the New Deal consensus, allowing Chicago School libertarians to peddle simplistic views of the relationship between the government, the citizen, and the economy. Stoller reserves his sharpest critiques not for Big Business or Wall Street, but rather for educated elites on his own team who, after a century of looking out for small businesses, farmers, and workers, quickly abandoned them for free trade, private equity, and, eventually, Amazon.

To ensure the complete and lasting victory of neoliberalism, its forces buried the New Deal vocabulary. Financial elites, their allies on Capitol Hill, and a not-yet-discredited cadre of libertarian economists dismantled the guardrails on capitalism erected by New Deal policymakers from both parties. Thereafter, to suggest that the market might need some degree of oversight was to invite scorn and derision.

The resurrection of the anti-monopoly lexicon and its history is a positive step toward a new economic consensus. So is the fledgling movement to build a 21st-century industrial policy, incubated by intellectuals on the right and now embraced by mainstream politicians. Business culture also appears to be shifting, and it has once again become possible to be “pro-business” while objecting to returns earned through labor arbitrage. Even JPMorgan Chase’s Jamie Dimon now suggests that the efficiencies-over-everything-else shareholder economy might not be right for our democracy.

Throughout Goliath, Stoller asserts that the past century’s antitrust struggles can and, indeed, must inform the challenges in front of us. A conversation about Amazon is incomplete without understanding the pitched battles that unfolded in the 1930s between federal regulators and the A&P chain store. It might surprise young investors and managers today to discover that for decades, American law protected producers’ ability to price their own goods. The monopoly issue is also one of national security: As we grapple with the implications of Big Tech’s cozy relationship with an ascendant, cyber-forward China, we might look to the 1930s, when the federal government belatedly intervened to prevent Standard Oil and Alcoa from helping Hitler reconstitute the German war machine.

For investors it is Stoller’s discussion of the impairment of small business that is most valuable. From the turn of the 20th century until the mid-1970s, American policymakers deliberately structured the economy to support the producer and reward production. Reaganism — with plenty of help from the New Democrats — inverted this order of operations, asserting the consumer as the prime mover (and beneficiary) of American capitalism. As Amazon shows, anticompetitive and illegal behavior, not to mention widespread labor abuse, is now tolerable, as long as the annual letter to shareholders proclaims the right amount of “customer obsession.” Stoller rightly points out how neoliberalism’s consumer focus not only distorts our economy, but also perverts the economic rights of democratic citizenship, reducing them to opportunities to obtain goods quickly and buy them cheaply.

For all of the bleating about innovation at business schools and elsewhere, American entrepreneurship is in a perilous state. Despite a ten-year bull market, annual small business formation is still at only two thirds of its pre-recession levels. Over a longer horizon the picture only grows bleaker. In the 1970s new firms (defined as those less than one year old) accounted for approximately 15 percent of all American businesses. Forty years later that percentage hovers in the mid-single digits. Our winner-take-all economy is creating fewer businesses and, as a result, inferior investment opportunities. Our business culture now seems purpose-built to celebrate founders and companies whose entire business model can be described as seeking monopoly, while avoiding mention of the collateral damage to other sectors of the economy.

Populism has long been a dirty word to the business community. When it comes to the crude, incoherent Trump variant, corporate America may be forgiven for being dismissive of what is far more likely to be a transitory presidency than one that results in a new ideological stadium. But the anger that propelled Trump to office is not an aberration. Behind the scenes a new cohort of conservative intellectuals are preparing for his departure, whether it occurs this year or in 2024. Like Fox News television host Tucker Carlson, they may disagree vehemently with liberals on the social issues, but when it comes to the economy, they are far closer to Elizabeth Warren than Paul Ryan. Their progressive counterparts have taken notice, laying the groundwork for the establishment of a new stadium in the near future.

But investors dismiss an increasingly bipartisan economic populism at their own peril.

As Julius Krein, founder of the “American Affairs” journal and an ardent critic of Reagonomics, highlighted recently, American class conflict might soon reach a front closer to home: Millennial HENRYs (High Earners Not Rich Yet) working in finance, law, and consulting have started to realize that when it comes to the fruits of a distorted, monopolized economy, they too will be on the outside looking in. America’s top 9.9 percent, who still depend primarily on professional labor to accumulate wealth, are on a strikingly different trajectory from the top 0.1 percent, who earn via capital gains. For the first time, America’s young bourgeoisie is calling into question the return on investment of an arrangement that requires outsize student debt, climbing coastal living costs, and delayed family planning.

These trends should interest those who allocate capital with a long-term view. As a new generation of antitrust crusaders in Congress takes up the debate, investors would do well to participate constructively in the conversation. A new stadium will be built, and its potential location and ground rules will be influenced, at least in part, by whether or not those who control and administer capital are able to confront just how bad things have gotten. This will be a challenging shift in mind-set — from the luxury boxes the game always looks pretty good.

Besides, in the nosebleeds they are celebrating their tax cuts.