Illustration by II

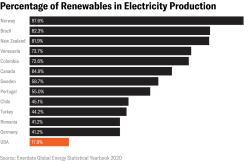

Energy transition is a thing. And it should be, because the environmentalists are winning: As of 2020, renewable energy accounted for 20 percent of U.S. power generation.

There’s a lot of well-deserved excitement about recent progress toward renewables, but despite the popularity of renouncing oil and gas, it will be decades before clean sources like wind and solar fully replace fossil fuels. We can’t flip a switch and have clean energy. New technologies need scale and storage that can only grow as fast as the infrastructure builds out.

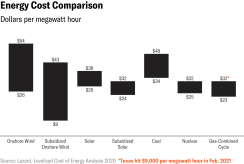

Full decarbonization of the electric power sector is pivotal to the global climate mitigation efforts outlined in the Paris Agreement, which President Joe Biden signed on his first day in office. Unfortunately, energy replacement isn’t as straightforward as one might presume by looking at the familiar cost metrics. Marginal costs of production are converging toward grid parity, but simple cost comparisons aren’t easy, very accurate, or reliable. First of all, comparing technologies operating in stand-alone mode is absurd since they have to be operated in combination. More importantly, nobody has any real idea what natural gas prices — or the prices of anything — will be in the future.

No Model Is Perfect

It doesn’t even matter what the numbers are because transitioning U.S. energy supply to 100 percent renewable power sources will not be feasible for the next several decades. No, it’s not because solar panels do not produce energy when the sun isn’t shining. And it’s not because turbines do not produce when the wind isn’t blowing, either. Comedian Ron White’s best sketch is about a guy who ignores a hurricane warning and ties himself to a tree because he thinks he’s in good enough physical condition to withstand hurricane winds. White observes wryly, “It isn’t that the wind is blowing. It’s what the wind is blowing. If you get hit with a Volvo, it doesn’t matter how many situps you did that morning!”Similarly, the obsession with the relative costs of alternative energy sources completely misses the point.

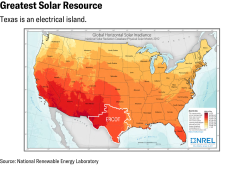

For the U.S. to begin producing more renewable energy, the renewable energy that’s generated must have somewhere to go. Today, that can’t happen because there isn’t one unified U.S. grid. Even if it started raining windmills and solar panels, we couldn’t do much with them because our grid is in the way. There is a nearly impermeable electrical seam that divides America’s power grids. The current grid is divided into three major parts: The Eastern Interconnection, the Western Interconnection, and Texas (which has its own separate grid because it isn’t really part of the U.S.). While all three of these grids are connected, they operate almost entirely independently of one another, with little ability for one to send excess electricity to help meet the demands of another. In fact, they barely interact at all — exchanging approximately one-tenth of 1 percent of their power.

This is why the country’s two largest states — California and Texas — can’t keep the lights on when there’s a heat wave or winter cold snap. While their political leaders waste time trading barbs, both have intermittently been “unable to perform even basic functions of civilization,” as Senator Ted Cruz infamously tweeted during a recent California heat wave. And none of this had to happen. A unified grid would have addressed today’s problems.

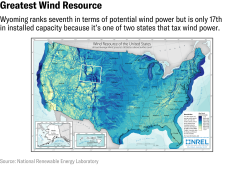

The current grid was built under a 19th century paradigm designed for gas lighting. It’s a one-way model in which power is generated at centralized sites and sent through distribution lines to end users. But renewable energy generation facilities — particularly large-scale solar and wind farms — are more widely distributed. And not equally: Fifteen states account for 87 percent of U.S. wind energy potential, most geographically far from the urban load centers where most of the country’s energy is consumed. We need a 21st century vision. To unlock the full potential of renewables, there needs to be a single, continent-wide supergrid that can transmit electricity in any direction. China gets it, Europe gets it — why doesn’t the U.S.?

It won’t be possible for the U.S. to throw off fossil fuels until it can get the abundant wind and solar energy in the central part of the country to the cities on both coasts. You can have all the renewable energy in the world, but if you don’t have transmission, you have nothing.

The problem is not the technology or even the cost. The problem is political. But that’s another story.

Large amounts of wind, solar, and storage will be needed in varying densities in many locations and transmission will be critical to move energy from where it is produced to where it is consumed. Sunlight can be harvested in the winter months, so an increasing number of small farms in Minnesota are planting solar panels instead of crops — and funneling electricity to the grid year-round. But you need a national market for clean energy in the same way you need a national market for fresh produce, and for the same reason: Home vegetable gardens don’t have enough scale. Even if everybody had rooftop solar and a battery in their garage, the physics just don’t work — it would only be part of the solution. Carbon-free electricity can’t be done with software and batteries alone because it would require a crazy number of batteries. Batteries are complements to, not substitutes for, transmission. Wires are cheaper.

A Transmission Renaissance

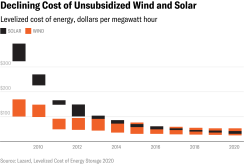

Building national-scale transmission is not a new idea. Nearly 100 years ago, a Chicago newspaper trumpeted the value of a truly interconnected grid. A unified grid makes sense whether the energy source is all coal, all gas, all nuclear — or a mix of anything. Maybe hydrogen will be a savior energy source; maybe it won’t. Either way, it will require a smart, continental-scale, 21st century grid that can spread it around and balance the flow of power more efficiently.There have been dramatic improvements in the cost-competitiveness of wind and solar, but timing is everything because cross-seam transmission has a substantial impact on the location, size, and type of wind and solar that can be developed in each region. Solar farms are a third more powerful today compared to 2016. Wind currently generates more than 7 percent of the nation’s electricity, and it will only keep rising. Giant wind turbines generate about twice as much energy as smaller ones, and the next generation will be taller than any building on the mainland of Western Europe. The metric everyone in the industry fawns over is the levelized cost of energy (LCOE). It’s the amount of energy generated divided by the cost of building and operating the plant. In English, that means it’s cheaper to build new renewables than to keep the old crap we have.

The cost to produce wind and solar has declined by 70 percent and 90 percent, respectively, over the past decade. Solar and onshore wind are now the cheapest sources of new-build generation for at least two-thirds of the globe, and there are plenty of innovations in the pipeline that will drive down costs further. So there is a path to zero-carbon electricity.

The International Energy Agency recently declared solar power to be the cheapest form of electricity in many places around the world, and in the best locations solar is now “the cheapest source of electricity in history.” Unlike fossil fuels, which get more expensive as we pull more from the ground, renewable energy gets cheaper as we make more, yet it’s not being deployed anywhere near fast enough because the U.S. transmission grid is inadequate. The grid we have today is congested and old. In many places, you can’t pump any more electrons onto the grid because it would overload the system. Most transmission and distribution lines in the U.S. were constructed in the 1950s and ’60s with a 50-year life expectancy. The broken, century-old, 3-inch hook that may have started the deadliest wildfire in California history was purchased for 56 cents around the end of World War I. A grid upgrade will require a doubling or tripling of the size and scale of the nation’s transmission system, and until the grid is connected we are going to have to keep burning coal and natural gas — and lots of it — for decades to come.

The Path Back to U.S. Competitiveness

Transmission is the lever for increasing production of electricity from the sun and wind, but we take infrastructure for granted. The grid is collapsing because it’s boring to people. Nobody gets too excited about high-voltage transmission lines because they’re ugly. They’re tall and they emit a penetrating, incessant buzz. But the U.S. needs more because the places where the sun shines brightest and the wind blows hardest aren’t where most people live — and there is essentially no storage of electricity on the grid. To bring the energy from areas of the U.S. where power is produced cheaply and with few environmental impacts to the people requires a strong transmission network. Since the sun shines and the wind blows at different times of the day in different parts of the country, long-distance transmission reduces the impact of the variability of wind and solar. It can address over-generation issues and increases the reliability of the electrical grid.Of the new energy capacity added to the electrical grid last year, 78 percent came from renewable sources. Wall Street can’t throw enough money at wind turbines, solar panels, and batteries, but transmission and substations — not so much. The technology is on the shelf; it hasn’t changed in decades. We know how to hang wires and ship power hundreds of miles. The grid is what Tesla invented — Nikola, not Elon. It’s not complicated; no magic technofix is needed. Upgrading the bulk power transmission network would create millions of new, local, and non-exportable jobs, but the stuff people get really excited about in 2021 involves door-to-door food delivery, e-commerce, robots, cloud-to-edge integration, or artificial intelligence.

Overlooked is the fact that Industry 4.0 and the “digitization of everything” require electricity, making it one of the economy’s most important costs. Businesses moved offshore in the 1980s because human costs were lower; those firms can come back because those costs are less important today. Data centers want to go to the places with the lowest energy costs. Similar to how the interstate highway system drove down business costs across the country, low-cost electricity will enable America’s prosperity and power economic growth. It’s fast becoming the input of greatest importance to North American competitiveness.

Transportation now accounts for one-third of America’s greenhouse gas emissions each year, and every carmaker has an electric vehicle on the market or in the pipeline. In 2019, the Tesla Model 3 was the best-selling car in the Netherlands. Not the best-selling electric vehicle, the best-selling car. Full stop. Electric vehicles are coming, and coming fast, but society won’t register the full potential of electric vehicles because clean transportation and clean energy aren’t the same thing, and the overwhelming majority of our electricity still comes from fossil fuels. Electric vehicles don’t burn gasoline, but that doesn’t make them “clean” transportation. A Tesla charged in West Virginia, Wyoming, Missouri, Kentucky, Indiana, Utah, North Dakota, Nebraska, Ohio, Wisconsin, New Mexico, or Colorado is a coal-powered car. These states generate more than 50 percent of their electric power from coal, and Montana — at 49 percent — just missed the cut. Greener electricity lifts all boats and the grid is getting cleaner over time, but it’s still not at zero emissions. If every American switched to an electric car, the country’s electricity use would go up by 25 percent.

Virtual Storage

The most ambitious interpretations of clean energy aspire to more than simply decarbonizing the power system; the real goal is a net-zero economy. To avert the possibility of catastrophic climate change, we must stop burning things; that means converting all of our transportation, residential, commercial, and industrial systems so they are powered solely on electricity, with most of that newly generated juice coming from forests of wind turbines and oceans of solar panels. “Everything on the Net” and “Electrify Everything” are green mantras, but achieving this would require U.S. electricity production to increase by a factor of three. To meet all this demand with variable energy sources like wind and solar, you have to do two things: overbuild the capacity and connect all the seams.Perhaps even more important than how much electricity will be consumed is the question of when it will be consumed. With a macro grid, power can flow to the eastern U.S. when demand peaks there on weekday mornings, then shift westward as the day goes on. Meeting demand like this reduces the need for constructing new generating plants or adding battery packs; grid planners call this virtual storage. Sunny regions that produce solar power during the day swap with regions that produce wind power at night.

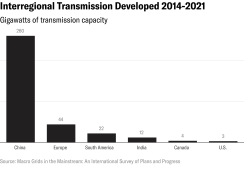

To ensure America best fulfills its renewable energy potential, our electricity grid technology must be upgraded and expanded. To date, such planning has not featured prominently enough in public conversation and government policy; yet the time frame to get the licensing and environmental approval to begin construction of a transmission line is about ten years. Google, Facebook, and Amazon are notable among a clutch of U.S. technology giants leading the corporate procurement of green energy, but they’re not investing in the grid. With the current antiquated electric grid and transmission system, the U.S. is way, way behind its peers in the development of a more interconnected, next-generation power grid capable of moving electricity from one distant geographic region to another. By enabling the integration of higher levels of dispersed renewable power, a modern, climate-resistant infrastructure will help America compete internationally with countries that have already built high-voltage, long-distance lines.

Interest in interregional transmission has grown worldwide, on every continent, because there is a strong appreciation for the high economic value of sharing bidirectional power flows. In 2020, for the first time, renewables generated more electricity than fossil fuels across the European Union.

Over the past two decades, Germany has spent a lot of money to accelerate its uber-ambitious, renewable-centric energy-transition plan, Energiewende. With a goal of taking renewables from 2 percent of all German electricity to nearly 40 percent, it is by far the most aggressive renewable push in the world. And the U.K., a leader in offshore wind, in 2019 generated over 40 percent of its power with wind and only 2 percent with coal. To replace big coal with thousands of smaller wind and solar units, Europe has been connecting its grids. On December 8, 2020, NordLink — the massive “Green Cable” — was energized, creating, for the first time, an interconnection between Norway and Germany. The soon-to-be-energized IFA-2 will connect the U.K. grid with France’s power grid by year’s end. Europe is well on the way toward the creation of a supergrid interconnecting the whole of Europe and neighboring countries and linking the rich wind resource of the North Sea with the solar resources in northern Africa, Italy, and Spain.

Europe’s not the real threat, however. There’s that pesky country that starts with the letter “C.” China recently completed five times more high-voltage interregional transmission than Europe and over 80 times more than the U.S. And China plans to invest close to $900 billion more in the next five years to further develop its power grids.

A Green Electric Backbone

Updating the grid is going to be expensive: at least $150 billion of investment and probably closer to $200 billion. That’s a lot of coin, but here’s the good news: These investments will earn 9 to 11 percent because that’s the regulated return on transmission assets. This is what’s allowed under the regulatory compact that was first laid out in the Binghamton Bridge Supreme Court case of 1865 because transmission is a natural monopoly. This isn’t like the deregulated power generation market; there’s actual competition there so independent power producers like Calpine Corp. can — and do — go bankrupt. Investors can lose everything. Not here — these returns are guaranteed.The formula is pretty simple. I won’t bother to explain it:

Total revenue requirement = rate base × allowed rate of return + expenses

Hope-and-Pray Trades

The opportunity is massive because we all have the same problem, whether we’re the CIO at a pension fund or retirees managing 401(k)s. Everyone is asking, “Where can we put our money, earn a yield, and not structurally lose it?” While cheap borrowing costs have been a boon for corporate America, the same can’t be said for pension managers, endowments, and insurance companies that need to generate returns that match their long-term obligations. As debt rated A or above paying 5 percent has virtually disappeared, institutional players have elbowed out banks as lenders in leveraged buyouts and to junk-rated companies — often accepting few safeguards to lend. Spurred by a desperate search for returns, asset owners are throwing caution to the wind and pushing deeper into lower-rated debt and progressively more complex investments across asset classes, including real estate, infrastructure, private equity, and credit in an effort to juice returns. Why?Biden just unlocked private investment in the grid. It is the most fundamental infrastructure there is — a giant power cord that connects supply with demand. These are valuable assets so the private sector should be lining up to invest. David Swensen made his reputation by championing investment in novel asset classes, and this one is sitting right in front of us: X marks the spot. Pensions and large companies like Apple, Alphabet, Microsoft, and Amazon are sitting on mountains of cash that should be jonesing for private finance initiative projects to build transmission for the federal government, give operational control to a regional transmission organization, and receive the approved return from ratepayers. Do more than consume the power — bank the returns!

It’s good for the pensions, it’s good for employment, it’s good for the earth; it’s win-win-win. Win cubed!

Loopy pinwheel turbines are a hassle to build, the biggest Ikea furniture-assembly projects anyone’s ever seen — just buy the ugly towers that connect them. The American Society of Civil Engineers gave energy infrastructure a D+ and estimated weather- and age-related outages to have cost the U.S. economy a number with a denomination that starts with a “T.” Is there anybody who doesn’t think improving the resilience, reliability, and security of the electricity delivery system is a good idea?

Tearing Pages From an Old Playbook

We can do this. America is at its best when backed up against the ropes. We put a man on the moon in under ten years back in the ’60s. In fact, the grid’s greatest leaps forward took place when the federal government instructed regional utilities to interconnect during World War II to ensure a steady flow to Automation Alley to build tanks and planes. Another leap took place during the Cold War and the space race when the government directed utilities to send excess power from huge hydro dams in the Pacific Northwest to Southern California via the 846-mile, 3,100-megawatt Pacific DC Intertie (which was a fan-flipping-tastic investment for the Bonneville Power Administration and the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power).The ultimate solution to zeroing carbon emissions is going to take a holistic approach balanced across all our assets. The key is working together. The U.S. needs a national electricity policy. Interregional transmission is a job that was never clearly assigned to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, the Department of Energy, or any other entity, so the grid is influenced by a variety of decision makers, including over 200 investor-owned utilities, ten federal power authorities, over 2,000 publicly owned utilities, about 900 rural electric cooperatives, seven regional transmission organizations, 48 state regulatory bodies, and many state and federal agencies. It’s understandable why Texas wanted to create an electrical island, but ERCOT is short for the Electric Reliability Council of Texas. Don’t laugh; it takes away from the message. Energy from neighboring states could have helped Texans survive their extreme winter storm.

The quick development and deployment cycle of multiple vaccines in response to the Covid-19 pandemic showed us what science is capable of when experts set their minds to achieving a common goal. Pandemics pose a significant and immediate threat to the world’s health and economy — but so does global warming. Embracing the new generation of electrification technologies, powered by renewable energy, will help us decarbonize the economy. We can do this quickly: 2020 taught us that immediate action can be taken when met with unprecedented crises.

If you want to save the planet and you want to do it fast, the biggest contribution you can make today isn’t to run out and buy a Tesla; it’s to deliver Ron White’s punchline.

The roadmap for a 100 percent renewable future is only feasible if we fix the grid — and no one’s even talking about it.

The grid is the Volvo.

Aaron Bloom works for an energy developer and is on the board of Energy Systems Integration Group, a nonprofit educational organization whose mission is to chart the future of grid transformation and energy systems integration. Its latest thinking can be found here.

Richard Wiggins is a CAIA charterholder. The CAIA Association is the professional body for the alternatives industry with a mission to improve investment and societal outcomes for investors.