Photographs by Jonno Rattman

It’s night in New York City. Steam from a manhole billows across Wall Street. An American flag flies in the foreground as a camera pans from an office overlooking the city’s lights to a solitary woman watching her Bloomberg terminal flash the plummeting stock chart of Canadian drug company Valeant Pharmaceuticals.

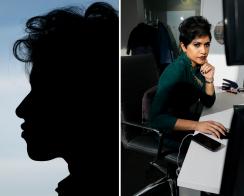

With the Empire State Building in the background, Fahmi Quadir comes into full view. “I was always this Pollyanna growing up,” she says — the first words uttered in her starring role in the Netflix documentary series Dirty Money, whose third episode, “Drug Short,” tells the epic tale of the Wall Street battle over Valeant, which lost 90 percent of its value between 2015 and 2016, taking down billionaires and making an internet heroine of Quadir, one of a small group of short sellers who bet, correctly, that the drug company’s price gouging, questionable tactics, and massive debt burden could not be sustained.

Yet the film’s noirish setting takes Quadir far beyond the world of Pollyanna. Instead, it casts her as something of an exotic femme fatale, continually draped in dark: dark hair, dark nail polish, dark, deep purple suede designer dress.

“I do my work in the shadows,” she says in a later scene, riding in a taxi through the streets of Manhattan, her dark eyes shielded from the sun by mirrored sunglasses.

Few people had ever heard of Quadir before the release of Dirty Money in January of last year. She has since stepped out of the shadows. At the age of 27 — after working only two years as an analyst at the small hedge fund that had shorted Valeant — Quadir launched her own hedge fund last January. The child of Bangladeshi immigrants who settled in the Long Island town of New Hyde Park, the young woman called her new firm Safkhet Capital, named after the Egyptian goddess of mathematics and wisdom.

At the start of 2018, Safkhet had two employees (both women) and about $6 million — a tiny amount for a hedge fund, even one dedicated to the risky business of short selling, a technique that bets that a stock will go down in price. Nonetheless, Quadir planned big. She immediately registered Safkhet with the Securities and Exchange Commission, looking forward to a big future that would draw in the type of institutional investors that largely eschew a fund whose manager has such a slim track record as hers.

Fortune favors the bold: 2018 would end with a market meltdown that left famous hedge fund managers nursing losses and facing redemptions. Quadir, on the other hand, is on the upswing. She starts 2019 with more than $35 million and five investors, with most of them signing up during the second half of last year. She’s also boasting a net gain of 24.14 percent during a year when the S&P 500 fell 4.4 percent.

“To start a fund and to make it through a year, there's nothing that makes me more proud than that,” Quadir exclaims in Safkhet’s sparkling midtown Manhattan office in a Sixth Avenue skyscraper, its third home since launch.

Safkhet is all the more impressive since the number of women running their own hedge funds is a minuscule fraction of the total. Only 2.5 percent of the approximately 10,000 hedge funds are headed by women, according to Meredith Jones, who tracks diversity in finance and authored Women of The Street: Why Female Money Managers Generate Higher Returns (and How You Can Too).

Short selling is also largely a man’s game — one that lost so many players in the decade-long bull market that Hedge Fund Research quit posting returns for a short-biased index at the end of 2017. But if recent trends are any indication, women can also play what can sometimes be the nastiest, most testosterone-dripping game on Wall Street, one replete with Twitter wars, lawsuits from target companies, and all types of intimidation.

At former hedge fund manager Whitney Tilson’s most recent short-selling conference, held in December in New York City, five out of 22 presenters were women short sellers — although none are well known.

That seems to be the way most of them like it. When contacted for this story, one well-regarded female short seller — 221B Capital's Jillian McIntyre, whose Twitter page background affirms that “she is badass” — firmly said she was “not interested” in participating.

Quadir, however, is not shy in expressing her opinion on the subject. “All short sellers are outsiders,” she offers. “And women are especially outsiders in this world.”

Quadir’s decision to run a short-only fund with only a few investments raised concerns among more experienced short sellers and investors — a point she alluded to in her first-quarter letter, as she thumbed her nose at the “naysayers” who said launching her fund would be “impossible, unwise, and certainly not executable by two millennial women with less than a decade combined of financial market experience.” She giddily reported that Safkhet had managed to post a 15.8 percent net return during the quarter — its very first.

“Perhaps one day the naysayers will say, ‘We told you so,’ but we’re betting they won’t and we promise you we will fight like hell to continue to prove them wrong,” she wrote.

The naysayers were saying just that by the end of the very next quarter. By June, Safkhet had given away nearly all of those gains, ending virtually flat, at 0.18 percent net. “This past quarter we were in a near constant battle against the faceless algorithms driving the ‘short squeeze’ bandwagon’s momentum,” she confessed. “Never did we expect that on such a compressed timetable, we would have such polarized performance.” (Faceless algorithms, of course, are the enemy du jour for any market move a manager didn’t foresee.)

Quadir had not anticipated having to trade constantly just to stay above water. But by the end of June, she said she had closed out seven shorts — or 30 percent of the fund’s positions — accounting for a 0.2 percent loss. In general, she has a one-year horizon for the shorts to pan out. “If we don't see it playing out, then we'll exit,” she says. The fund currently has 15 short positions, which Quadir says is “the limit of our intellectual capacity.”

Following the second-quarter reversal, she turned sanguine. “Knowing you’re right but that the market will always think you’re wrong at least until you become insolvent is the short-seller lesson everyone knows but few adhere to,” she wrote in the letter. “Knowing you’re wrong before the market knows you’re wrong is an adage I have yet to be told, perhaps reflective of an industry where the most common pitfall is a dearth of self-awareness and unwillingness to look inward.”

Thinking back now on the comments made in her first letters to investors, Quadir has no regrets.

“I don't take back my comments about saying ‘fuck you’ to the naysayers,” Quadir says, knowing that people are still wondering whether she is — as she puts it — just a “one-hit wonder” for her Valeant short.

In a nod to her famous short, Quadir has a dartboard of former Valeant CEO J. Michael Pearson on the back of her office door on a coworking floor at 1345 Sixth Avenue. There’s not much room for anything else. Both Quadir and her sole employee, analyst Christina Clementi — a newly minted MBA from Yale University’s School of Management who previously was at Kelso & Co. and Arden Asset Management — work in a 200-square-foot box of an office. (The floor has spacious conference rooms and lounging areas.)

Quadir’s route to hedge-fund land was less obvious. She had worked as a consultant at Deallus Consulting covering the pharmaceutical industry, a job she landed shortly after graduating from Harvey Mudd College in Claremont, California, where she’d majored in mathematics and biology. “I thought I would be an academic,” she recalls — the common profession for Harvey Mudd graduates. “I thought I was going to be a mathematician, a scientist, a professor; just devote my life to knowledge.”

Plus, she had disdain for the world of high finance.

“I'm pretty sure on numerous occasions up through college, I said, ‘I will never work on Wall Street,'” she laughs, noting that she started college in 2008, the year of the financial crash. “Seeing these multimillion-dollar hedge fund managers, bankers, executives that were, in my view, getting away with murder, whereas looking across suburban Long Island, you saw people struggling. That kind of income disparity always bothered me.”

Yet finance is in her genes. Her father, now retired, was a small-business banker in Long Island at New York Community Bank during the financial crisis. Her elder sister — whose husband is a hedge fund manager — is a corporate attorney at Citigroup in charge of foreign-exchange compliance.

It was perhaps only natural that the social justice warrior of the family would end up on the short side of things. “I am driven by unsavory businesses,” she says, explaining what motivates her to look into a company as a short target.

A chance encounter with a woman she met at the National Museum of Mathematics in Manhattan — a Harvey Mudd alum hangout — led her to hedge fund manager Michael Krensavage, who was seeking to hire someone to look into short selling ideas in the healthcare industry for his eponymous firm, Krensavage Asset Management.

Once Quadir joined, Krensavage turned to his old friend and well-known short seller Marc Cohodes to train her on the techniques of short selling. The two hit it off. “Marc played a major role as far as helping me get the exposure at Krensavage that I needed, as far as my positions, sizing them up, and being able to take concentrated short bets, because that wasn't something that Krensavage was used to,” says Quadir.

Both Krensavage and Quadir had been eyeing Valeant, which had become more of a short target after its ill-fated attempt at taking over Botox-maker Allergan in 2014.

But the catalyst for the stock’s initial dive didn’t come until more than a year later, in September 2015, when then-presidential candidate Hillary Clinton began talking about predatory drug pricing, and Valeant's stock began to fall. News about suspicious behavior of Philidor Rx Services, the specialty pharmacy that marketed Valeant’s high-priced drugs, broke in October, and the stock never recovered.

It was a moment of serendipity for Quadir. She’d put on the Valeant short in June 2015 — just as the stock was nearing its peak. At more than one point, she says, Krensavage — a $300 million long-short equity fund — was 10 percent of all the short interest on Valeant.

Soon other short sellers began to pile on, but Cohodes was still on the sidelines. “I convinced Marc to go short Valeant, which was difficult,” says Quadir, who thought Valeant’s price increases and its debt burden were on a collision course of unsustainability. She notes that Cohodes’ reluctance was personal: He is close to Jeffrey Ubben, co-founder of ValueAct Capital, the hedge fund that more or less created Valeant by hiring the now-disgraced Pearson, who led the debt-fueled acquisition binge that drove the stock sky high for years.

The young woman’s ability to turn Cohodes’ head on Valeant led to an alliance that has continued. One of her first non-pharmaceutical shorts was Canadian financier Home Capital Group, a well-known Cohodes short. While at Krensavage, she also shorted Concordia Healthcare Corp. In all of these cases, the hedge fund did not publicize its research or positions, leaving the public attacks to Cohodes, who was also short.

Though Krensavage’s Valeant short helped the firm earn a 14 percent return in 2016, Quadir abruptly left Krensavage in the spring of 2017 for somewhat mysterious reasons. “The situation was untenable,” says Quadir, who declined to explain what happened, except to acknowledge that a legal situation between her and Krensavage is “unresolved.”

What she will say is that “as a young woman who is starting out in this industry, I had a lot of great opportunity at Krensavage. My experiences there, and how well I was able to do there, allowed me to start this fund. But a part of starting the fund is also making a change in the industry, and being my own boss and creating the culture as I see fit.” (Krensavage did not return a call for comment.)

By August 2017, Cohodes was publicly promoting Quadir’s new fund in a Bloomberg article that said Safkhet expected to raise $200 million — although so far it has fallen far short of that.

“It is a hard world for a female,” says fraud consultant Sam Antar, who met Quadir through Cohodes and visited the Krensavage office to discuss accounting issues at Concordia. “To make it in the financial world, if she can get a patron like Marc to help her along, she’s going to do it.”

Cohodes, who recently said he was quitting the world of short selling — at least for suspected frauds — declined to comment for this story. Quadir said he is not an investor in Safkhet.

“So young, so early in her career,” explains one sympathetic short seller, referring to her fame. “I feel that can impose a decent amount of insecurity: ‘Do I have another trick up my sleeve?’”

Her meteoric rise has certainly led to some skepticism from peers.

“My impression is that she’s definitely intelligent — but also, I would say, overzealous and argumentative,” says a short seller who has socialized with Quadir, adding, “I find her a difficult person to be around.”

It’s clear that Quadir may have to do more to prove herself, not just to her fellow short sellers but also to investors — especially institutional ones.

“It comes down to a chicken-and-an-egg situation. If you have multibillion-dollar allocators, they need to invest at least $100 or $200 million, and they don’t want to be 50 percent of the fund,” Quadir says.

Safkhet requires investors to place at least $3 million in the fund. “I really want investors who understand what we're creating. And we're completely unhedged, short only. So it's a small investor base; you really have to understand the kind of volatility that will come with it,” she explains. The fee structure is also complicated. To collect performance fees, Safkhet has to have both positive alpha (i.e., do better than the market) and positive absolute returns (i.e., above zero). The incentive fees are calculated on a sliding scale, and there is a management fee of 1.5 percent.

Getting off the ground led Quadir to sink her entire net worth into working capital, including paying for the expensive midtown digs and the costs associated with setting up an institutional fund. “I've had to put all my money into legal expenses,” she says, noting that most funds her size aren’t registered with the SEC. “But I wanted to set up the fund and have all the infrastructure in place.” Safkhet is also set up in the Cayman Islands, but has not yet launched an offshore vehicle.

If big institutions balk at her lack of experience, a select few relish the fire in the belly that often comes with youth. “I want them hungry. I want them eager,” says Donna Walker of Sire Management, a $150 million fund-of-funds that was one of Safkhet’s first investors.

Walker says recommendations from Cohodes, a former hedge fund manager, and Bronte Capital founder John Hempton — both of whom were short Valeant — led her to meet with Quadir as she began to market her fund.

“The more I talked to her, the more impressed I was. She looks under every rock,” says Walker, referring to Quadir’s research. Walker says Quadir is also good at what the investor calls the art of short selling: “The hardest thing about shorting is knowing when to press the button and when not to press the button.”

Cohodes may have helped teach Quadir that art. He has also been helpful in other ways. In its first year, Safkhet found that one of its most profitable shorts was MiMedx, the small, Georgia-based biopharmaceutical company that came under constant attack on social media from Cohodes — attacks that led to a visit from the FBI in 2017 after he tweeted that he would “bury” then-CEO Parker Petit in a shoebox. Petit has since been fired, and MiMedx now faces multiple federal probes into its accounting and sales practices. The stock fell 86 percent in 2018 to $1.79.

Qadir claims she didn’t get the idea from Cohodes, who only began shorting MiMedx in the fall. Instead, she says, the idea was first brought to her in 2015 by Elliot Favus, a doctor whose Favus Institutional Research offers consulting and research on healthcare companies and who previously worked as an analyst at Och-Ziff Capital Management.

But outside of talking about MiMedx to investors, Quadir has not joined the chorus of short sellers lambasting it on social media. She says she does not intend to become an activist short who broadcasts her research, leaving that to other short sellers with whom she shares information — like Cohodes and Viceroy Research’s Fraser Perring, a British short seller who has also been publicly critical of MiMedx.

“As for all of the noise that often comes with good short targets, I try to avoid it,” she says. “Sometimes it can become a battle of personalities, and less about the fundamentals and stock. So since launching the fund, I've tried to withdraw from that echo chamber.”

While she says she “absolutely” benefits from Cohodes' and Perring's trash-talking her short targets, she says she has to be more circumspect. “I'm running an SEC-registered fund. I'm managing other people's money, so I need to be judicious about the risks and the litigation risks that I take on.”

Yet even in her relatively quiet and brief time as a short seller, Quadir claims she has faced the dark side of the business — a side that, according to the 28-year-old, includes hacked printers, fake emails, and accusations of nefarious friendships.

Last year, Quadir filed a Freedom of Information Act request on a company she believed “to be involved in money laundering and fronting for criminal enterprises.”

In response, she believes, the company initiated “cybersurveillance, including numerous hacking attempts with aggressive measures to obtain sensitive information about us and our personal lives,” she wrote to investors in August.

“We are not fearful,” she bragged in that letter. “When companies resort to such intrusive and illegal tactics against a small fry, perhaps we are not as small as they think we are and more importantly, perhaps it’s the company that’s shaking in its boots,” she added.

Quadir declined to tell Institutional Investor the name of the company, but said she’d received emails falsely purporting to be a journalist she knew, leading her to believe it was an attempted hacking.

That wasn’t all.

“We've received documents from lawyers, but it's not actually from those lawyers. And there was a time in my home — I have a basically defunct printer at my home — when suddenly, in the middle of the night, I think it was like 2:00 a.m., the printer just turns on and starts printing emails from whistleblowers. In the middle of the night!”

Quadir has since brought on cybersecurity experts “to clean everything,” she says. “I'm not concerned for my safety; I think this just comes with the territory. Did we expect it to all happen in the first year of launching? No. But it's just the lengths these companies go to intimidate.”

Quadir has also faced criticism for her relationship with Perring — whom she met through Cohodes and calls a good friend. Some of that was from Intellidex, a South African research firm, which accused Perring of plagiarizing a report written by a British hedge fund and suggested that Quadir is feeding him research.

The British investor has also become controversial in short-selling circles. In addition to the statements in the report by Intellidex — which was commissioned by advocacy group Business Leadership South Africa —Munich prosecutors have reportedly “issued a penalty order seeking to fine” Perring for suspected manipulation of one of his short targets, according to Reuters. (Perring, to Reuters, claimed that “he had not been informed of any possible financial penalty and that he had received conflicting information about the outcome of the investigation.”)

To her peers’ surprise, Quadir took the unusual step of defending Perring in one of her letters to investors. “We stand in solidarity with people and firms like Viceroy that have sought to expose criminality and fraud,” she wrote in her second-quarter letter, referring to what she called a “hit piece” for targeting Perring and Viceroy. She accused Intellidex of “propagating the mystique of a short-selling cabal. We unequivocally denounce the report along with its allegations and innuendos.”

“Cabal” may be too strong of a term, but there is little doubt that short sellers often share ideas and information. Quadir doesn’t deny offering research to Perring, saying, “Whatever company we're short, [we] will work with whatever we feel is the right strategy to distribute information. On a case-by-case basis, I'll discuss certain names if I think they can add value.”

That’s not illegal. But coordinated trading to try to bring down a company could be viewed as market manipulation by regulators. That’s an area she avoids. She says neither Perring nor Cohodes knows what’s in her portfolio, nor do they know her trades.

Moreover, some of Safkhet’s biggest hits in 2018 aren’t well known, including a short on Conn’s, a subprime retailer in the southern U.S. that finances home appliances. The company, which has not been targeted by activist short sellers (but has seen a few negative tweets from Cohodes), saw its stock drop 47 percent last year as its portfolio of loans suffered increased delinquencies. The company has attributed the drop to stricter immigration policies.

“When there's so much money available at such low rates, some of that money goes into the hands of bad actors. We've just seen such an explosion at these companies that have taken advantage,” she says.

One example that has gained some currency in short-seller circles is Health Insurance Innovations, which claims to offer short-term health insurance to those out of work. One of its partner companies, Simple Health, is under investigation by the Federal Trade Commission. Quadir believes the two companies are one and the same.

“It essentially covers nothing, and the consumers don’t even realize it.” she says. Health Insurance Innovations just last month became a focus of a barrage of negative tweets by Cohodes and Perring. Her short on it was also one of the biggest contributors to Safkhet's performance last year, Quadir says.

Some consider Tesla an inappropriate short for Safkhet. “If you’re a short seller and managing $30 million of other people’s money, you can do better than shorting Tesla,” says Citron Research founder Andrew Left, who went from being short Tesla to going long after he sued the company and learned more about it. “She is a bright girl. I know she’s capable of doing better than shorting Tesla.”

While smaller companies like MiMedx are easier to take down for a fund her size, Quadir says she’s not shying away from bigger ones. “We are short one of the largest companies in the world,” she says — coyly declining to disclose the name.

Ticking off a list of shorts may go a ways to proving to the world that Quadir has more to offer than her star turn in Dirty Money. The hedge fund manager acknowledges that she was fortunate in that case. “A lot of my circumstances, some of it's serendipitous, and maybe not even repeatable,” she says.

That said, “When you're so young and you have a big short under your belt, people are going to be skeptical. We're not all macho, testosterone-driven guys that are looking to see the world burn.”

But, she says, “I believe that they will always be skeptical.”