How well hedge fund managers describe their strategies in writing may say a lot about their performance, according to a new paper from four academic researchers.

A well-rounded vocabulary — defined in the paper as “lexical diversity” — could be an indication of better cognitive ability and trustworthiness, leading to higher returns, “superior” Sharpe ratios, lower volatility, and fewer regulatory and legal problems, according to Aalto University’s Juha Joenväärä, University of Oulu’s Jari Karppinen, Singapore Management University’s Melvyn Teo, and University at Buffalo’s Cristian Tiu.

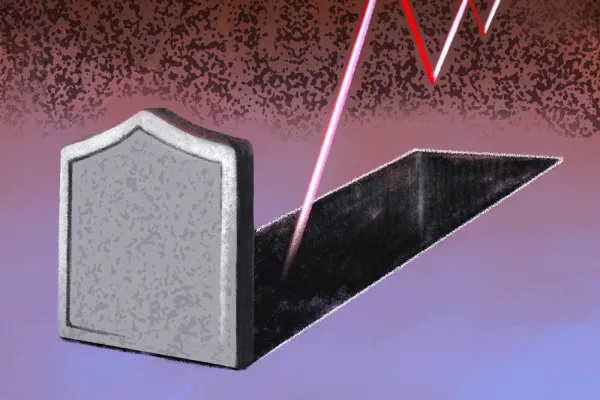

At the same time, strategy descriptions made up of overly long and convoluted sentences — “syntactic complexity” — could be a sign that managers “have something to hide,” Tiu, an associate professor of finance at the University at Buffalo School of Management, said Wednesday in a phone interview.

“It’s somewhat surprising because strategy descriptions aren’t something you expect to be that informative,” said Tiu. “They’re written once in the beginning of a fund’s life and the hedge fund could hire a marketing firm to write a description for them.”

[II Deep Dive: Hedge Funds with Strong, Powerful Names Attract the Most Money]

Still, Tiu and his three co-authors found ample evidence that expansive vocabularies were linked to higher returns, even after accounting for other possible causes of outperformance that would correlate with writing ability, such as the manager’s education. Overall, they found that hedge funds with the most lexically diverse strategy descriptions outperformed funds with the most lexically homogenous write-ups by 3.63 percent annually.

Funds with large lexicons also tended to “eschew idiosyncratic risk and tail risk,” the authors found, resulting in annualized residual volatility of 3.63 percent, compared to 4.19 percent for funds which used more repetitive language.

When examining hedge fund syntax, meanwhile, Joenväärä, Karppinen, Teo, and Tiu found that more elaborate sentence structures were tied to more regulatory actions, investment violations, and other civil and legal infractions.

For example, the authors quoted the strategy description of the Fairfield Sentry fund, which “gained notoriety as one of the feeders for Bernard Madoff’s fund.” According to the paper, one sentence of the strategy summary read as follows:

“The establishment of a typical position entails (i) the purchase of a group or basket of equity securities that are intended to highly correlate to the S&P 100 Index, (ii) the purchase of out-of-the-money S&P 100 Index put options with a notional value that approximately equals the market value of the basket of equity securities and (iii) the sale of out-of-the-money S&P 100 Index call options with a notional value that approximately equals the market value of the basket of equity securities.”

“This is the quintessential example of a fund whose strategy descriptive obfuscates rather than clarifies,” the authors argued.

In the phone interview, Tiu said that the findings could potentially be useful for investors looking to identify talented, trustworthy managers — or detect red flags. According to the study, investors might already suspect some connection between writing and investment abilities: The authors found that investors allocated more capital to funds with lexically diverse strategy descriptions compared to hedge funds with complex syntax.

“However, the capital that investors allocate to lexically diverse hedge funds is not sufficient to erode away their positive alphas,” the paper concluded.