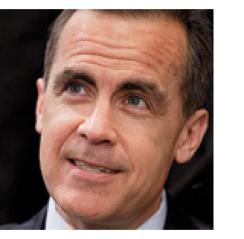

For a former Goldman Sachs banker from North America, Bank of Canada governor Mark Carney gets remarkably good press in the U.K. Expectations are high for Carney’s next posting as governor of the Bank of England. The first foreigner to take on the role, he’s untouched by the Libor scandal that has stained the reputation of some domestic contenders. As chairman of the Basel-based Financial Stability Board, he has strong reformist credentials. But it’s not clear how Carney, 47, can rescue the economy or protect British interests in the European banking union (see page 6). His disappointment could be compounded by an uncomfortable life in the media spotlight.

Describing the onetime Harvard reserve ice hockey goalie as “a hard-working, earnest guy, not a superstar,” one old friend thinks Carney will need lots of luck with the macroeconomic environment. The International Monetary Fund calls for the sluggish U.K. economy to grow just 1.1 percent in 2013 after a slight contraction this past year. In October the IMF said Britain was doing everything possible to relax monetary policy through quantitative easing and low interest rates, which suggests Carney will struggle to make an impact after he replaces Mervyn King in July.

Meanwhile, the euro zone is driving the European banking union. Carney could negotiate safeguards for his adopted country that would stop the currency bloc from imposing its rules on other European Union members, but such terms might be decided before he arrives. Being a Canadian and an outsider may not help. “The Europeans will find a North American an awkward proposition,” says one veteran regulator who knows Carney. But Carney is no stranger to Britain. He earned two graduate degrees at Oxford, where he met his wife, Diana Fox, a U.K.-born economist.

Leading the BofE will be a big administrative burden too, reckons Philip Shaw, London-based chief economist at bank Investec. Seasoned deputy governors Paul Tucker, who was passed over for the role, and Charlie Bean may both step down in 2014. Carney’s friends in Ottawa, Canada’s low-key capital, have other fears. Noting that “Mark and his family have never lived in a fishbowl before,” one of them worries that they will get a “rude awakening” from the British tabloid press.