After five years of tepid growth, investors can be forgiven for wondering if the U.S. is headed for a decades-long slump like Japan’s. While the U.S., like Japan before it, is suffering from the repercussions of a massive real-estate, stock-market and banking-system collapse, we see three reasons why the U.S. economy and stock market are likely to escape Japan’s fate.

Faster Postcrisis Deleveraging

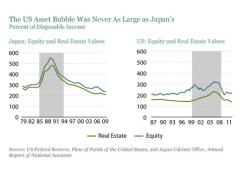

Purging the enormous debt amassed during the global credit bubble is the biggest challenge facing the U.S. (and most developed countries). Though daunting, the U.S. debt problem is much smaller than Japan’s, in part because asset prices were never as inflated. At the height of their respective bubbles, the ratio of equity and real estate values to disposable income in Japan was roughly double the ratio in the U.S., as shown in the display below.

Further, in Japan, aggregate income was falling along with asset prices, while debt loads remained constant. In the U.S., aggregate income has grown as debt levels and service costs have declined, further easing the burden.

A key factor behind the U.S.’s deleveraging success has been its ability to sustain economic output. The U.S. Federal Reserve slashed interest rates, which lowered borrowing costs and weakened the dollar, which in turn lifted exports. The early boost in federal-government spending — even as tax revenues plunged with the recession — helped offset cutbacks by businesses and households, and remains an economic support.

The U.S. also moved much more swiftly than Japan to deleverage its banking system. In Japan, the government propped up insolvent (so-called zombie) banks for over a decade. In the U.S., banks were forced to write off many of their toxic mortgage assets, particularly those held in securitized form; as a result, the banks had to recapitalize.

Corporate debt was a huge problem in Japan, but Japanese companies did not move aggressively to restructure; “zombie” companies persisted in Japan too. U.S. companies, less leveraged to begin with, improved their balance sheets and cut costs. Household debt, which had skyrocketed during the credit bubble in the U.S. but was not a major issue in Japan, has fallen sharply since 2008, both as a percentage of disposable income and in absolute terms, largely due to defaults. It has even returned to its long-term trend.

As a result, the U.S deleveraging has progressed much more rapidly, although it will take many more years to return to balance. While government debt has risen, we expect strengthening economic activity and rising tax revenues to ultimately help reduce government deficits. History shows that the faster a country deleverages after a financial crisis, the less overall damage to the economy and the better the prognosis for future growth.

Lower Deflation Risk

Deflation is a destructive force. Once it takes root, as it has in Japan, it becomes self-reinforcing and extremely difficult to dislodge. It also makes it much harder to dig out from under excess debt.

Applying lessons learned from Japan’s experience and the U.S. Great Depression, the U.S. Federal Reserve moved quickly and aggressively to combat deflationary pressures at the onset of the recession by injecting massive liquidity into the financial system via ultralow interest rates and quantitative easing. Though the Japanese ultimately followed the same path, they took more than a decade to get started, far too late to outrun expectations of deflation.

Today, U.S. inflation is expected to remain positive, but low. With nominal interest rates extremely low, real interest rates are negative. This situation is terrible for savers, but stimulates consumption and investment and helps banks to recapitalize, because they earn a spread on their higher-yielding investments. Ultimately, negative real interest returns should encourage investors to shift to more risky assets in order to improve returns.

Better Demographics

Japan’s shrinking workforce and longer life spans are causing significant structural imbalances: there are ever fewer workers to generate tax revenues to support growing retirement and healthcare programs. The ratio of workers to nonworkers is higher in the U.S. than in Japan and should stay that way for decades to come, thanks to a higher birth rate and a more open immigration policy. While the rising cost of government healthcare programs remains an issue in the U.S., it is primarily the result of escalating medical costs. We believe that it remains solvable with a bit of political will.

In sum, more aggressive government and corporate actions to deal with problems in the U.S. are bearing fruit. Indeed, corporate profits have eclipsed precrisis levels, and the financial health of American corporations has never been better.

For now, however, all investors can see are reasons for worry. They have responded by shortening their investment horizons and dumping equities in favor of safe-haven assets, such as U.S. Treasuries and gold.

But this won’t always be the case. As current economic and financial imbalances resolve, we expect investors to regain their confidence to take more risk.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AllianceBernstein portfolio-management teams.

Joseph Gerard Paul is chief investment officer-North American Value Equities at AllianceBernstein.