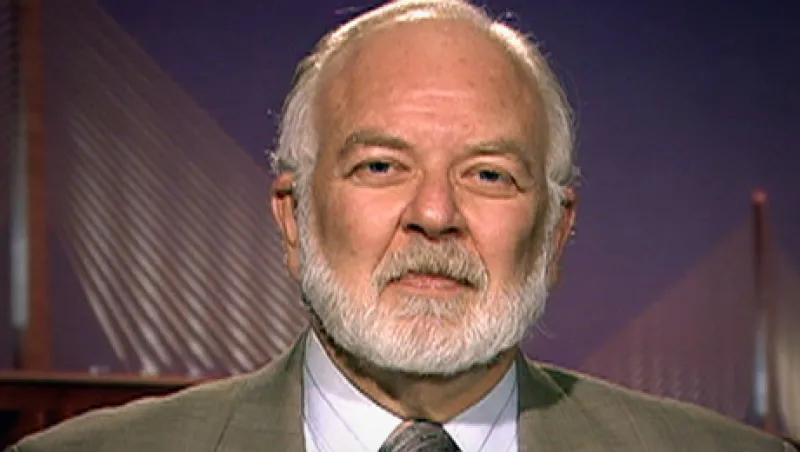

It doesn’t always pay for an analyst to be right, especially when regulators are way behind. Just ask bank analyst Richard Bove.

Bove certainly wasn’t looking to become the poster child for retaliation by a company he followed when he wrote a report titled, “Who is Next?” in July 2008. In the wake of IndyMac’s failure, he used two metrics to rank the banks he thought were at the greatest risk from the growing real estate bust. Within days, BankAtlantic Bancorp — No. 10 by one metric and No. 12 by the other — sued him for defamation.

Bove was with Ladenburg Thalmann at the time, and he says he left the firm in February 2009 rather than go along with a settlement under which the firm had agreed to pay the bank holding company a reported $300,000. (Ladenburg declined to comment on the settlement, citing a confidentiality agreement, or on Bove’s departure.) Now with Rochdale Securities, Bove hired his own attorney, racking up $800,000 in legal bills, and he says he still “owes $700,000, not a small amount to me.” He settled with the bank holding company in June 2010 but without any admission of liability on his part, and “I paid them nothing,” Bove says. But, he was forced to drop his coverage, he says and was told, “If you open your mouth about this company again, we’ll sue you again.”

So how does Bove feel now that the Securities and Exchange Commission has finally filed suit against the Fort Lauderdale–based bank holding company and its CEO and chairman Alan Levan?

“I don’t feel vindicated,” Bove says in an interview with Institutional Investor, “I feel upset, frustrated, annoyed that the system simply doesn’t work for independent research.”

Bove is deeply paranoid about being sued again and struggles with what he wants to say on the record. But he notes that “it’s a fact” that the bank holding company was already under investigation by the SEC in 2007 because that disclosure was made in its publicly available SEC filings. If the SEC had moved sooner, “instead of doing nothing for that five-year period,” Bove says, “not only would investors have avoided losing all that money they lost, but that lawsuit [against Bove] would have fallen apart.” When Bove wrote his report on July 15, 2008, the stock was a split-adjusted $23.47. As of this January 30 it closed at $3.01 for a loss of 87 percent.

The SEC announced its lawsuit on January 18th. Levan was charged with making “misleading statements in public filings and earnings calls to hide the deteriorating state of a large portion” of the bank’s real estate loan portfolio as far back as the first two quarters of 2007. For instance, the SEC quoted an email exchange between “two senior BankAtlantic loan officers” in which they described the loans in its commercial residential portfolio as “ticking time bombs” and “explosive piles of crap,” less than three weeks before the July 25, 2007 second-quarter earnings call, during which Levan “maintained his position that the bank was concerned only about the BLB [builder land bank] loans,” the SEC charged. Levan has, of course, fired back. In a press release issued the same day, he promised “when this case goes to trial, we will have our opportunity to address each and every one of the SEC allegations.”

The SEC wouldn’t comment on whether the publicity over the lawsuit against Bove peaked their interest or whether they used any of his research materials. “We don’t talk about our investigative steps,” says Glenn Gordon, the associate regional director for the SEC’s regional office in Miami.

But Bove’s attorney, Thomas Holt, a partner with K&L Gates in Boston, says that he received a subpoena from the SEC asking for written materials from the lawsuit such as “transcripts of depositions of individuals at BankAtlantic,” and he complied. There are also newspaper reports out of Florida that note that the “explosive piles of crap” quote has been seen before in a shareholder lawsuit.

While Levan is bemoaning the fact that BankAtlantic Bancorp has “to spend time and money in defending this [SEC] action,” Bove is currently pursuing a case against Ladenburg Thalmann for the $700,000 in legal bills he racked up after he left the firm. Ladenburg, for its part, says that it “paid significant legal fees on Mr. Bove’s behalf.”

Meanwhile, citing Bove’s troubles with BankAtlantic Bancorp, the Investorside Research Association, the trade organization for independent research providers, is once again trying to gain some attention for the issue of “issuer retaliation.”

The organization released a white paper in September 2010, noting that “there are many examples of instances where [independent research providers] sounded an early warning on companies headed for trouble,” and got sued by the companies.

“What I learned is that your freedom of speech is limited to the amount of money you have to defend it,” says Donn Vickrey, a member of the subcommittee that produced the report and the director of research at Gradient Analytics, a Scottsdale, Arizona, independent research provider that focuses on the quality of earnings.

In 2005, Gradient was sued by online discounter Overstock, and Vickrey says his firm spent “over $1 million, for sure” to defend itself at a time when the company had about $6 million in revenues. “It was a pretty big hit,” he says. Gradient settled that case for an undisclosed amount. In 2006, his firm was also sued by Biovail, a Canadian pharmaceuticals company, and that was “a very nasty campaign” that included a “60 Minutes” piece alleging that Gradient (then known as Camelback) was “somehow in cahoots” with Steve Cohen of SAC Capital Partners to drive down the stock, “though we didn’t know him,” Vickrey says. But in that case, at least, the SEC got involved pretty fast. The SEC sued Biovail in March 2008, and it settled. There were other regulatory actions as well. When Biovail’s lawsuit against Gradient was thrown out of court in 2009, Gradient turned the tables and brought a lawsuit against Biovail for malicious prosecution. “We settled about a year ago and did quite well,” he says.

Still, as a result of the lawsuit, “we changed what we do considerably,” says Vickrey. “We don’t cover companies for as long as we did or report as frequently,” he says. In the Overstock case, the company argued that “we were trying to knock the price down by reporting repeatedly when it wasn’t our intent to do that,” he says. As a result, Gradient now limits its reports on a company to “one, possibly two, in a quarter.” And the firm has decided not to cover a company for “much more than a year,” he says. Gradient’s focus has always been on timely ideas, so it was always the case that it would cover a company for longer than that only “if we found a company we thought was problematic,” he says. They covered Overstock for two or three years, but they’ve now decided “if our thesis doesn’t play out in a year, maybe it’s time to move on.