Plunging oil prices since mid-2014 have led many equity investors to shun energy stocks. We think that’s a mistake. By studying the aftermath of previous oil shocks, we believe, investors can gain insight to prepare for a possible rebound.

The price of oil has recovered in recent weeks from a trough. Brent crude has climbed 32 percent, from a low of $45.25 per barrel on January 26 to nearly $59.79 on February 20. And investors pumped $4.9 billion back into U.S.-domiciled energy sector exchange-traded funds in December and January, according to data from New York–based consulting firm Strategic Insight.

But timing a big rebound isn’t easy. The recent uptick in oil prices has been driven by an accelerated decline in U.S. drilling activity, a squeeze on short positions and events in the Middle East — which can all change quickly. Since so many variables affect the oil price, another leg down might yet precede a more sustained recovery.

It’s better to take a long-term view. As my colleagues explained in a recent post, we believe that over time the underlying dynamics of production will push oil prices back up again.

Understanding the context of energy shocks is the first step to investing. Some are driven by supply issues, whereas others are caused by demand. In early 1986 oil collapsed after Saudi Arabia flooded the market with excess supply. But in 2009 oil prices tumbled on concerns that year’s global economic slowdown would undermine demand.

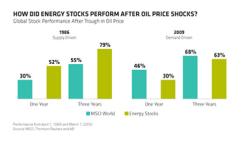

So, what happened with energy stocks? In 1986 global energy stocks outperformed the broader market for a year and three years after the oil price bottomed (see the left panel in chart 1; click to enlarge). By contrast, in 2009 energy stocks underperformed the broader index (see the right panel in chart 1). U.S. stocks posted similar patterns in both cases.

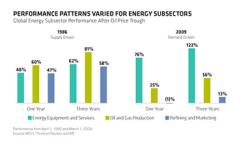

Taking a closer look, we find that the performance of energy subsectors was varied (see chart 2; click to enlarge). Equipment and services companies surged in 2009 yet lagged behind production companies in 1986. Refiners and marketing groups stagnated after the 2009 episode. These observations highlight the need to take a selective approach to the energy sector by evaluating how current conditions may unfold and affect diverse companies in an oil price recovery.

Today the situation is largely driven by supply. Energy stocks are trading at extremely low valuations, and dividend yields are extremely high. For example, today the dividend yield of the three U.S. oil majors versus the S&P 500 is higher than it has been for 20 years, implying a fear that companies may be forced to slash payouts to shareholders.

These trends can help investors make informed choices. First, look for energy companies with a structure and business model that are likely to work well even without a full recovery of oil to $100 a barrel or more. Some exploration and production companies, as well as integrated groups, can do well with oil above $70 a barrel, our research suggests. Our checklist includes companies with high-quality oil fields, lower-cost production and resilient balance sheets to support dividends. Companies that don’t depend on capital spending to generate earnings also have a much better chance of maintaining dividend payouts through stressful times.

Second, be selective with oil services companies. Some investors have started to move back into services, recalling the sharp rebound in 2009. But that was a demand crisis. Today, even if oil starts to bounce back, we think it could take a while for companies to ramp up new supply that will increase demand for services, thereby suppressing profitability in the subsector for longer. Some services groups are technical leaders, however, playing a vital role in the long-term development of deepwater fields, where most incremental oil supplies are found. These companies also tend to have strong balance sheets that should help them through the current downturn.

Third, the outlook for refiners and marketing companies is complex. These businesses are not as sensitive to oil prices as are other parts of the sector. Here, profits are driven mainly by spreads — between oil prices, as well as between crude prices and product prices. Global overcapacity in refining could constrain profitability, even if demand begins to pick up. Still, some U.S. refiners have big cost advantages and could benefit from wider spreads between U.S. and global supplies, as well as from a buildup of crude because U.S. producers aren’t allowed to export.

Avoiding the energy sector is a risky strategy that could leave investors behind in a recovery. Yet investing in energy sector ETFs means that an investor will have indiscriminate exposure to the energy sector at a time when a discriminating approach is especially important. By focusing on valuation, cash flow and business-specific fundamental analysis, we believe, investors can gain conviction to reconnect with energy stocks for a long-term recovery.

Sharon Fay is head and CIO of equities at AllianceBernstein in New York.

See AllianceBernstein’s disclaimer.

Get more on equities.