Few companies “go big or go home” with more gusto than Fairfield, Connecticut’s General Electric. By announcing a $50 billion stock buyback, the global industrial conglomerate joins yet another elite club. Only Cupertino, California–based Apple’s buyback program, now pegged at an astounding $200 billion, exceeds the scale GE has proposed. GE’s buyback commitment is five times larger than its previous stock repurchases over the eight quarters through the end of March. Subject to price fluctuations, GE expects to retire up to 20 percent of its shares by the end of 2018.

The GE buyback is clearly tied to the company’s recent strategic decision to sell its finance unit, GE Capital, a move that will eliminate a big source of profits. Generating earnings per share will be a challenge despite the agreement to acquire Levallois-Perret, France–based power generation and distribution giant Alstom for $13.5 billion. The buyback, says analyst Steven Winoker at New York money manager AllianceBernstein, “is meant to offset dilution associated with the exit of GE Capital.”

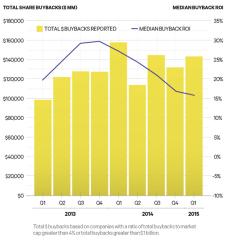

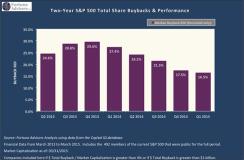

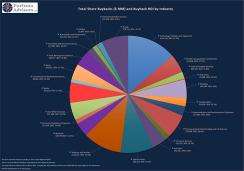

GE highlights a stock buyback trend that has not significantly eased even as pricier shares make so-called capital return programs, which combine repurchases and dividend payouts, riskier. In the eight quarters through the end of March, some 276 companies in the Standard & Poor’s 500 repurchased 4 percent or more of their market capitalization. In the first quarter of 2015, buybacks approached $144 billion, a brisk pace, if just behind the $158 billion in the first quarter of 2014. Since Institutional Investor initiated the Corporate Buyback Scorecard in 2013, companies meeting the 4 percent threshold have diverted $1.2 trillion to buybacks, or a median $128 billion per quarter.

“S&P firms know that annual revenue growth is slowing at this late stage in the cycle,” says John Blank, the chief equity strategist at Chicago-based Zacks Investment Research. Slower growth prospects combined with a strengthening dollar, growing piles of cash and low borrowing rates contribute to the case for buybacks. “Buybacks are the easy way to build up EPS when fundamentals are so soft,” he says. “It’s probably a signal of both weak operating earnings growth and, somewhat paradoxically, weak revenue growth performance.” The heart of that paradox is when buyback volume exceeds earnings.

| Buyback Scorecard THE S&P 500 AS STOCK REPURCHASERSBest & Worst CompaniesIndustry Comparisons |

Companies continue to spend heavily to buy back shares. Nineteen companies each repurchased more than $10 billion worth of stock in this scorecard. The latest GE initiative, scheduled to be completed by 2017, exceeds its 2014 earnings by more than three to one and its 2014 capital expenditures by a similar margin. GE’s buyback performance, however, has been lackluster over the past two years. Its repurchase program generated a 4.6 percent return on investment, putting it at No. 209 in 2015’s first quarter, down from No. 180 in the first quarter a year ago. In the first quarter of 2013, GE ranked 82nd, with an ROI of 26 percent.

Volume, timing and motives differentiate individual buyback programs. Some companies want to absorb excess shares in the wake of divestitures or shares issued to facilitate acquisitions. Cincinnati supermarket chain Kroger Co. has a long record of using cash flow from its stores to repurchase shares ever since it issued new shares in 1999 to merge with the Fred Meyer chain. “We started a buyback program to reduce dilution,” Kroger chief financial officer J. Michael Schlotman told Institutional Investor in 2014. At 71 percent ROI, Kroger currently ranks No. 3 in buyback ROI.

Apple’s buybacks served to placate activists like Carl Icahn and others who saw few better uses for the company’s huge amount of cash. The most recent scorecard shows that those buybacks have produced stellar results. Two years ago Apple’s buyback ROI was in the basement. But in this scorecard the company records the sixth-best ROI, at 54 percent. Apple’s buyback ROI exceeded its buyback strategy, a proxy for total return to shareholders, by 12 percent.

Buybacks often beget more buybacks. Apple recently announced a plan to boost its capital return program from $130 billion to $200 billion by March 2017.

Not everyone has performed as well as Apple, with an uncertain market taking its toll. In the first-quarter scorecard, median two-year buyback ROI for the S&P 500, in which companies retired at least 4 percent of market capital, ticked down from the previous quarter by one percentage point, to 16.5 percent. A year ago median buyback ROI for the S&P buyback cohort was 25.2 percent, off its peak of 26.8 percent at the end of 2013.

Current scorecard leader Dallas-based Southwest Airlines repurchased shares in all eight quarters, from a low of $39 million in the fourth quarter of 2013 to $315 million the following quarter. All told, Southwest bought back shares worth $1.7 billion, or 5.7 percent of its market capital. The investment nearly doubled in value, to $3.3 billion.

No. 2 on this quarter’s scorecard is Orlando, Florida–based Darden Restaurants, which owns and operates more than 1,500 family-style restaurants. Darden, which has been the target of hedge fund activist campaigns, deployed a portion of the proceeds from the sale of its Red Lobster chain to buy back shares. An accelerated repurchase program took shares off the hands of two institutional investors, Goldman Sachs and Wells Fargo Bank. Buyback ROI at Darden surpassed 82 percent.

Some buybacks, like Darden’s, are intended to mollify activists, whereas others grease the wheels of strategic alliances. For example, buybacks helped Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, drug distributor AmerisourceBergen Corp. ink a purchasing pact with Deerfield, Illinois, drug retailer Walgreens Boots Alliance. Terms of the deal allowed Walgreens to buy 7 percent of AmerisourceBergen plus warrants amounting to 16 percent of the drugstore company’s outstanding shares, exercisable between March 2016 and September 2017. Anticipating potential dilution when warrants are exercised, notes analyst Ann Hynes at Mizuho Securities, AmerisourceBergen began repurchasing shares. So far, the company’s timing has been excellent, and it ranks No. 5 on the current scorecard.

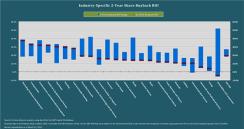

Three other health care equipment and services companies join AmerisourceBergen at the top of the scorecard: Irvine, California, heart valve manufacturer Edwards Lifesciences (No. 4) and managed care health insurers Anthem (No. 7), based in Indianapolis, and Humana (No. 8), headquartered in Louisville, Kentucky. Humana announced a $2 billion buyback in September 2014 after reporting a dip in net profit as benefit costs increased.

Atlanta’s Delta Air Lines (No. 9) and Cambridge, Massachusetts, biotech Biogen (No. 10) fill out the top tier.

At the other end of the ranking are two capital goods companies, a media company and a consumer durables and apparel retailer. Four energy companies ended up in the basement as well, hurt by the slump in oil prices. In dead-last place Houston-based oil and gas equipment supplier National Oilwell Varco saw its repurchased shares lose 62 percent. One spot above, London-based Noble Corp., a contract oil and gas driller, lost 52 percent. By contrast, Tesoro Corp., a San Antonio, Texas–based refiner, ranks at No. 11 with a buyback ROI of 51 percent.

For the past two years, six sectors come in near the top of their buyback ROI ranges and 14 are near their bottoms, with a handful — telecom services, utilities, and consumer durables and apparel — somewhere in the middle. Technology hardware and equipment, transportation, and food and staples retailing still show strength. But with so many sectors near their lows, the S&P 500 in the latest scorecard languishes near the bottom of its ROI range.

Click chart to enlarge.

In this scorecard a median company retired shares equivalent to 6.7 percent of its market capital. Buybacks at 13 retired more than a fifth of market capital. One of the latter is CF Industries, at No. 47, which bests all but two of 15 companies in the materials sector, beating the median ROI in its peer group by two to one.

Click chart to enlarge.

Buyback strategy at CF is part of a rigorous approach in managing a global competitor in the manufacturing and distribution of nitrogen-based fertilizer products. “We really think of this as a machine in trying to grow cash generation through nitrogen capacity per share,” Kelleher says.

A string of buybacks in combination with new revenues from acquisitions tested CF’s metric. CF now generates 143 tons of nitrogen capacity per 1,000 shares of stock, a three-fold increase since 2010.

A market climate favorable to buybacks can override earlier guidance from the company. CF had warned analysts to anticipate a pause in buybacks during the first quarter of 2015. When conditions unexpectedly favored buybacks in that period, CF returned to the market. “We took the view that we had a good handle on cash flow, knew where we were going and that it made sense to be in the market after saying we would not be in the market,” Kelleher says.

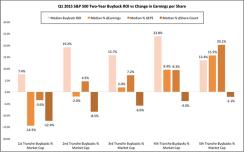

No matter what motivates companies, buybacks share a common effect: As the number of shares falls, EPS tends to rise. In the current scorecard Fortuna analyzed this relationship by matching buyback ROI quintiles with changes in EPS. Overall, the data confirms what we expected: Buyback ROI and EPS generally move in tandem. The top tranche in median buyback ROI recorded the top median percentage change in EPS. Lower tranches behaved similarly, with the fifth tranche recording the lowest median percentage change in EPS.

That’s a general observation that applies to companies in aggregate. Results for individual businesses are more difficult to predict. Houston’s Cameron International Corp., a supplier of measurement and control equipment for oil and gas producers, repurchased almost a fourth of its shares, a higher percentage than any other company in the current ranking, over the eight quarters through the end of March. Nonetheless, its EPS slid by more than 57 percent as buyback ROI took a pounding, falling by 23 percent.

Grouping companies in buyback ROI quintiles highlighted similar reductions in share count. However, the median change in EPS for each group fell sharply descending through the quintiles. In the top buyback ROI quintile, a median company reduced share count by 6 percent and posted a 36 percent increase in EPS and 40 percent buyback ROI. The bottom quintile did not feature aggressive buybacks as a rule. The median company in that group bought back 6 percent of its shares but posted an 11 percent decline in EPS and an 8 percent slide in buyback ROI. Instead of signaling good news, buybacks at a fifth of the companies signaled that they would be generating lower EPS in the future.

Across the board, companies hoping to improve market performance or EPS with buybacks, rather than by growing the business, will often find the going rough. As Fortuna CEO Gregory Milano concludes: “Our study showed that EPS growth from buybacks added about half the value versus EPS growth from operations.” Operations still matter.

Get more on equities.