In the early 1990s, Oak Investment Partners was a venture capital trendsetter. The firm pioneered the recruitment of female Harvard Business School graduates as associates; the industry affectionately (if chauvinistically) dubbed them the Oakettes. Oak charged management fees and carries that were among the highest in the industry and eschewed traditional compensation by rewarding deal makers — partners and associates — with a share in the profits of their own deals. When some of Oak’s limited partners challenged the firm’s practices, they were “disinvited” from participating in Oak funds.

The firm could get away with that then. Today, not so much. Oak now finds itself in an existential crisis. Its post-2000 funds have generated low-single-digit returns. Many of its early partners have retired, and the firm has suffered defections. Worst of all, Oak has been slammed by allegations that what it called a “rogue” partner committed a fraud that authorities say went on for more than a decade. There’s even talk the firm may be considering shutting down its most recent fund and returning the remaining cash to its investors.

In fact, the scandals at Oak, which include insider-trading and money-laundering charges, raise broader questions about venture firms and whether they operate with adequate controls and accountability. How closely are these firms, with their long cycles and often illiquid, private and opaque investments, monitored by LPs, gatekeepers and regulators?

Oak was founded in 1978, about the same time venture firms such as Accel Partners, Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, Mayfield and Sequoia Capital were launched. The firm was not based in Silicon Valley but in Westport, Connecticut. Edward Glassmeyer, a former marine, got his MBA from Dartmouth College’s Tuck School of Business before starting at Citicorp Venture Capital in 1968. Glassmeyer left Citi for a new venture firm, Sprout Capital, launched by Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette. There he met Stewart Greenfield, who had organized the advanced programming technology department at IBM Corp. in the 1950s before joining Sprout in 1971.

In 1974 the pair formed Charter Oak Enterprises, a merchant banking operation, while raising money for what would become Oak Investment Partners in 1978. The first Oak fund, with investors such as American Express Co., Citicorp, Connecticut General, Corning, Harvard University and 3M Co., totaled $25 million.

The firm focused on early-stage technology, such as mainframes, disc drives, PCs and software. Returns were high, which led to more funds, each larger than the last. But as the funds grew, returns fell, Oak investors say. The firm explored new investing areas and recruited Gerald Gallagher, a former DLJ retail analyst (later vice chairman of Minneapolis-based department store chain Dayton-Hudson), to head specialty retailing. It prospered from investments that included Staples, Office Depot and Whole Foods.

The dot-com meltdown of 2000 took its toll, and like many venture firms, Oak scrambled to escape the carnage. It shifted its focus overseas, although many in the industry were skeptical that it had the expertise. But Glassmeyer was confident: “It makes less of a difference where you are,” he said in a 2009 interview with the National Venture Capital Association (NVCA). “We’re doing a lot of work in Korea, China and India, and we haven’t really touched on that, and our companies need to be globally aware, and able to compete at ‘world prices’ — think Huawei [Technologies Co.],” a Shenzen, China–based telecommunications business.

By then Oak had become a multistage firm, with partners operating independently and coming together to raise money. Greenfield began splitting his time between Connecticut and Santa Fe, New Mexico, where he had gotten involved in conservation issues. Bandel Carano operated solo in San Francisco. And the firm recruited young foreign talent like Iftikar Ahmed, Angel Saad Gómez and Allan Kwan to gain access to emerging markets.

Ahmed, a native of Assam, India, arrived at Oak in 2002. Known as “Ifty,” he had graduated from the Indian Institute of Technology in New Delhi, been a Baker scholar at Harvard Business School and worked at Goldman Sachs Group and Fidelity Investments. His wife, Shalini Aggarwal, came from an affluent Indian immigrant family; attended Connecticut boarding school Lawrenceville, Princeton University and HBS; and worked at Goldman Sachs.

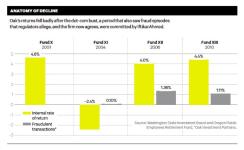

Oak’s four funds launched after 2000 were relative disasters: Funds X, XII and XIII generated internal rates of return from 4.6 to 4 percent (see chart, above) and Fund XI lost 2.4 percent. In 2009 one of Oak’s largest investors, the Washington State Investment Board, exited venture investing. Oak’s XIII Fund struggled to raise slightly more than half of the $1.5 billion it had targeted. As fundraising grew difficult, the firm focused on sectors such as health care, financial technology, even private investments in public equity (PIPEs). Last year three Oak partners — Andrew Adams, Patricia Kemp and Ann Lamont (the last an Oak managing partner) — announced they were forming Oak HC/FT Partners, with Glassmeyer, now 73, as a special adviser. They then closed the first round of a $400 million fund.

In April, Oak’s problems escalated. The Securities and Exchange Commission announced an indictment against Ahmed, 43, an Oak general partner since 2004, and his friend Amit Kanodia, a private equity investor at Boston’s Lincoln Ventures, for insider trading. The two allegedly made more than $1 million trading in shares and options of India’s Apollo Tyres as it tried to acquire Findlay, Ohio–based Cooper Tire and Rubber Co. Kanodia, the SEC charged, had picked up an inadvertent tip from his wife, who at the time was Apollo’s general counsel, then passed it along to Ahmed and a third “tippee.”

Then in May the SEC announced even-more-devastating charges: that Ahmed had transferred $28 million in illegal profits to accounts under his control at the expense of Oak investors. The agency froze his assets and charged him with fraud and self-dealing. The firm wrote to LPs that its review of investments in which Ahmed had directly participated suggested he was “only” involved in three, from Funds XI, XII and XIII that totaled $31 million. The deals represented 0.71 percent of LP capital commitments for Fund XII and 1.44 percent of Fund XIII.

Oak quickly brought in FTI Consulting, a Boston-based financial forensics firm, and New York’s Schulte Roth & Zabel, its outside counsel, to investigate further. And it hired New York crisis management firm Sard Verbinnen & Co., which assigned the job to Ellen Davis, a former public information officer for Preet Bharara, U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, who had prosecuted hedge fund firm Galleon Group’s Raj Rajaratnam for insider trading. Oak’s strategy against Ahmed pretty much followed the Bharara playbook. The firm fired Ahmed and relied on a few friendly journalists and releases from the government to tell the story.

After the internal investigation, Oak shared its findings with the SEC. Oak in a statement to Institutional Investor said: “After we discovered Mr. Ahmed’s fraudulent conduct, we commenced a comprehensive investigation of all his transactions and immediately reported the matter to law enforcement. Based on our investigation, we determined that Mr. Ahmed was a rogue employee who repeatedly circumvented Oak’s policies and procedures in carrying out the criminal scheme. We also engaged in a thorough review of our internal controls and are taking the necessary steps to enhance those controls.”

The rot was more extensive than anyone imagined. In August the SEC noted that the U.S. District Court in Connecticut had granted its motion for a preliminary injunction to extend the freeze to as much as $118 million in assets, including those in accounts held by Ahmed’s wife. The SEC alleged that Ahmed had been running the fraud for ten years, regularly depositing cash into accounts held in his and his wife’s names.

Still, while insider trading is notoriously difficult to monitor, the size and nature of the alleged fraud cases at Oak raise questions about how Ahmed could have executed them, some while he was a relatively junior employee, without someone noticing.

In one recent transaction, according to the SEC, Ahmed persuaded Oak to commit $20 million to a joint venture that provided e-commerce services in Asia. The venture was formed with a Cayman Islands company based in China and a Singapore business controlled by a British Virgin Islands–registered entity. Ahmed provided documents and valuations, which the SEC alleges he falsified to justify the “grossly exaggerated purchase price,” changing $2 million to $20 million. Oak paid $2 million to the Cayman company and $18 million for shares owned by the BVI entity, which turned out to be a personal account Ahmed controlled.

A Federal Bureau of Investigation veteran who advises private equity firms questions Oak’s internal controls. Who was doing due diligence? Who was responsible for reconciling terms of the investment? How could the firm have authorized a payment, then not checked where the money ended up?

In 2009, Oak had lobbied against stricter oversight and greater accountability to LPs, part of an NVCA effort to keep venture funds from being categorized as potentially systemic risks.

“Venture capital is a trust-based business,” says a Silicon Valley investor whose fund has coinvested with Oak. “VCs don’t keep watch on their partners. But precisely because of that, it relies on internal controls and external auditors to keep the numbers straight. Where was Oak’s CFO? What was she doing?”

Oak’s internal controls were managed by COO Grace Ames, a Smith College graduate who had joined the firm in 1999. Ames reportedly testified in federal court, “There is a basis of trust that’s required within the partnership.”

That trust may be the problem. LP gatekeepers including Philadelphia’s Hamilton Lane and West Hartford, Connecticut’s Fairview Capital Partners would not comment on their investments in Oak or what they may have done to get compensation. At a May 2014 conference, Andrew Bowden, then head of the SEC’s compliance and examination unit, noted that agreements between LPs and GPs were vague on critical points, giving the latter too much latitude for misconduct. “If the limited partners were willing and able to stop these abuses, they would have done so long ago,” he added.

Until a few years ago, most LPs were reluctant to ask fund managers for hard financial data, says Scott Zimmerman, Ernst & Young’s Americas market leader for private equity. “Until the market meltdown in the late 2000s, superior investment returns from asset managers placed them in the driver’s seat, allowing them to pretty much dictate terms of engagement,” he says. In its 2015 Global Private Equity Survey, EY noted that LPs were requiring greater accountability, information and customized reporting.

Jennifer Choi of the Institutional Limited Partners Association, a Toronto-based trade group, agrees. For some LPs this need for information may have been triggered by a bad experience, she says. Others are trying to make sense of data presented in a variety of formats. But how revealing is better data if the firm itself can’t detect problems?

Limited partners have grown more aggressive. In March 2014, 13 LPs of San Francisco–based Burrill Life Sciences Capital Fund III removed G. Steven Burrill, the fund’s GP, after an audit found that the fund had paid $19.2 million to his designees and affiliates to “prepay” management fees or fund loans.

And what about the SEC’s role? Should the agency more rigorously monitor activities of private equity firms, especially when it comes to internal accounting and investor communications? Or are these instances of fraud private matters?

Meanwhile, in May the man at the heart of the scandal disappeared. Despite a court order restricting his travel to three U.S. states, Ahmed fled the country. In late July he surfaced in India. His lawyer said he was arrested by Indian authorities upon arrival and had been granted bail. (India has no formal extradition treaty with the U.S.) In August, Ahmed’s wife, Aggarwal, went to court in the U.S. on charges that she and her husband had engaged in money laundering. “Ms. Ahmed is 100 percent innocent of any wrongdoing. The government charges are no more than guilt by association — or here, guilt by marriage — and our laws require actual proof, of which there is none,” Priya Chaudhry of New York–based Harris, O’Brien, St. Laurent & Chaudhry told legal website Law360.com.

Chaudhry, who did not return calls from II, said Ahmed had been diagnosed with cancer in 2013 and that’s why he transferred assets to his wife.

Meanwhile, Oak’s trials have only begun. The scandal that started as an insider trading case now is an indictment of practices of a once-top-tier venture firm and the industry as a whole. Venture capital may never be the same.