When many global investors look at Asia these days, they see the spectre of sluggish growth. Take China, for instance. The world’s second-largest economy expanded by only 7.4 percent last year, its slowest pace since 1990, and will likely increase by just 7.2 percent this year, according to the Asian Development Bank.

The growth rate across all of developing Asia was 6.3 percent in 2014, and that’s unlikely to change this year or next, the Manila-based bank predicts.

But seen through the eyes of the region’s corporate leaders, Asia offers an almost overwhelming array of opportunities that they have only begun to tap. After all, while the real gross domestic product figures may signal a slowdown, the continent’s economies, taken together, are still the fastest growing in the world.

They’re also host to a mushrooming middle class that companies are keen to court. The Paris-based Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development predicts that by 2030, Asia will comprise 66 percent of the world’s middle-class population and generate 59 percent of middle-class consumption — more than double its current allocations.

With prospects like these it’s no wonder that some corporate chieftains see an upside to the slowdown. Budi Sadikin, CEO of Jakarta-based Bank Mandiri, says the Indonesian market is a fertile place for expansion, but rapid growth brings its own set of problems. “The challenge is, how can we develop infrastructure and human capital availability as quickly as we want?” the 51-year-old asks.

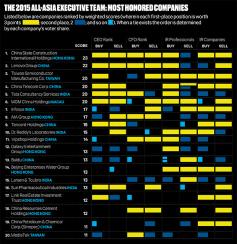

Similar questions are being asked by many of the leaders voted on to this year’s All-Asia Executive Team, Institutional Investor’s exclusive annual ranking of the region’s top CEOs, CFOs, investor relations teams and IR professionals. The 2015 team reflects the opinions of 820 buy-side analysts and money managers at nearly 500 firms that collectively manage an estimated $1.09 trillion in Asia (ex-Japan) equities, and from 625 analysts at 94 sell-side institutions.

When Sadikin joined Mandiri — the highest-ranked Indonesian company for a third year running — as managing director of micro and retail banking in 2006, the firm’s market capitalization was roughly $3.3 billion. By the end of 2014 (Sadikin’s first full year as CEO), that figure had ballooned to more than $20 billion, and Sadikin plans to reach $55 billion by 2020. Such breakneck growth is possible, he says, mainly because of Indonesia’s expanding middle class, which over the next 15 years will grow by 50 million — roughly equal to the entire population of South Korea — to 141 million, according to estimates from Boston Consulting Group.

“The 50 million Indonesians entering the middle class will need basic banking products like savings accounts, car loans and mortgages,” he observes. About one in four of Indonesia’s 240 million people currently have savings accounts, Sadikin adds, while only 15 million have credit cards and fewer than 5 million are mortgage holders. “Mandiri will definitely be in a very good position to ride the growth of the market,” he beams.

Late last year the bank entered a joint venture with two of the region’s largest vehicle distributors, Asco Automotive and Tunas Group, that allows Mandiri to extend car and motorcycle loans. The newly created company, Mandiri Utama Finance, is already the country’s third largest in terms of monthly car bookings.

In March, Mandiri purchased an 80 percent stake in PT Asuransi Jiwa InHealth Indonesia, a state-owned health insurance services provider.

These acquisitions have certainly helped the bank broaden its retail outreach, but its biggest boost has come from mobile and Internet-based banking, Sadikin says. “We are quite lucky because we can use the latest technology to push the expansion in retail banking,” he observes. “We don’t have to carry the burden of the old legacy system. We can piggyback on the infrastructure of our friends in the mobile companies.”

Back in 2006, Bank Mandiri had 600 branches, and 65 percent of retail transactions were conducted in person at those locations. Today the bank boasts 2,300 branches, but 92 percent of transactions happen through electronic channels — at ATMs or via mobile and Internet banking. Its Mandiri e-Cash mobile payments application, launched in May of last year, already has nearly 3 million subscribers and continues to grow. “Hopefully, in the next two to three years, [e-Cash] will accelerate the penetration of hundreds of millions of Indonesians that don’t have bank accounts,” Sadikin says.

Also sensing big opportunities in the growing demand for mobile services is China Telecom Corp., the nation’s largest fixed-line and third-largest wireless telecommunications services provider. CEO Xiaochu Wang, 57, says the Beijing-based outfit is undergoing “an Internet-oriented transformation,” and he sees “blue ocean opportunities” — that is, the possibility of building businesses where competition does not yet exist — in big data, cloud computing, information and communications technologies, the so-called Internet of Things, mobile Internet and mobile payments.

Still, Wang recognizes that collaborations have been important in moving into some of those spaces. Last year the company, which ranks third in China and fourth overall on this year’s All-Asia Executive Team, joined forces with two of its rivals — China Mobile Communications Corp. and China United Network Communications Group Co., known as China Unicom — to create the country’s first joint network infrastructure company. The new entity, China Communications Facilities Services Corp., will build base stations and telecom towers, among other projects.

In February, China Telecom received a long-awaited 4G license, which enables the company to provide faster access for web browsing and streaming music and videos, and by the end of March, it had signed up nearly 17 million 4G subscribers. The company hopes that figure will reach 60 million by the end of the year.

Computer, smartphone and tablet manufacturer Lenovo Group, which ties for first place (with web services provider Baidu) among companies in China and is No. 2 overall, has experienced phenomenal growth since 2009, when CEO Yuanqing Yang launched the Beijing-based company’s “protect and attack” strategy to maintain its core business in its home market and aggressively expand into emerging markets and the U.S. Revenue has more than tripled, from $15 billion to $46.3 billion in the fiscal year that ended in March, and the company’s share of the global PC market vaulted from just over 7 percent to roughly 20 percent.

Intensifying competition and a cooling of the Chinese consumer market’s hyperfast growth have made diversification increasingly important for Lenovo, Yang notes. Mobile is a central part of the company’s strategy, as evidenced by its most recent revenue breakdowns: PC sales generated more than 80 percent of revenue just a year ago and 63 percent in the first three months of this year, while the share of mobile sales nearly doubled, from 14 percent to 25 percent — even with record PC performance.

“We have become a diverse company, with three growth engines in PC, mobile and enterprise, and an expanding ecosystem/cloud business,” says Yang, 50. The rapid diversification has been aided by recent purchases: In October, Lenovo completed acquisitions of the Motorola Mobility smartphone business from Google, for $2.91 billion, and IBM Corp.’s x86 server business, for $2.1 billion.

Yang also plans to “attack” the increasingly competitive market in part by heading online. Lenovo’s new Internet-based smart device business, ShenQi GongChang, began operations in April with an online-only presence. Though many of Lenovo’s devices still sell through carrier relationships and offline, ShenQi’s online business model is a sign of things to come from the company — and a way to reach more of the market, he says.

Natarajan Chandrasekaran, CEO of India’s highest-ranked company for a fourth consecutive year, Tata Consultancy Services, believes the Mumbai-based information technology services provider — which pulled in $15.5 billion in revenues for the fiscal year that ended in March — will also find creative ways to foster growth. Through its Co-Innovation Network, or COIN, which includes the company’s own innovation labs as well as academic institutions and venture funds, TCS scans start-ups across the globe, and at any given point has a shortlist of some 200 fledgling enterprises that could be acquisition targets. Chandrasekaran has also overseen a restructuring of the company so that it is organized into 23 self-sustaining units focused on specific industries and clients within those sectors. Staying nimble, he says, allows TCS to “stay relevant.”

“We think that every industry will have to go through a massive transformation,” the 52-year-old says. “We call it the ‘digital reimagination.’”

Disruption is so inevitable, Chandrasekaran adds, that even TCS will have to find ways to reconsider and possibly reposition its business model. In early June it announced a new artificial intelligence product, Ignio, that could begin to do just that. The CEO describes Ignio as a “software robot” that will be able to discover ways to automate services and eliminate unnecessary or redundant processes currently performed manually, thus lowering operating expenses. He acknowledges that Ignio will take over some of the services that TCS personnel have long offered, but he’s not concerned about shrinking demand. “The market size is so huge that Ignio will open a lot of new possibilities,” he declares.

Oversize markets aren’t always a good thing. Casino and resort operator MGM China Holdings, the top-ranked company in Macau, is pulling back after a period of unprecedented expansion. “When we [went public] in 2011, I don’t think anyone, looking into the future, would have seen the growth spurt we encountered,” says CEO Grant Bowie. “In that regard, one of the great challenges of being in China is the level of unpredictability in this marketplace. Sometimes people believe that demand will always exceed supply.”

MGM China’s stock price peaked in January 2014, at HK$35.15, and has since fallen steadily, to HK$12.68 in late June 2015. Casino operators in Macau (the only place in greater China where gambling is legal) have struggled in part because of government crackdowns. Chinese President Xi Jinping has urged the local government to take a more aggressive stance to staunch the flow of illicit funds, and policymakers have recently proposed limits to the number of tourists allowed to enter the region.

Bowie, 57, concedes that between 2012 and 2014 “the market in Macau got ahead of itself.” He sees many of the changes being imposed by regulators as positive for his industry and company. “The critical point about sustainable industries and sustainable businesses is usually that they can evolve over time,” Bowie notes.

For example, diversification — one of the Chinese government’s objectives for Macau — is also an important commitment of the company. “As a pure gaming play, we need to diversify,” the CEO says. “We need to provide more opportunities into other entertainment and leisure activities to ensure that we and Macau retain our viability and success.”

To that end, MGM China has begun offering more restaurant, retailing and entertainment choices. But even there, predicting the best direction for the company’s evolution is proving difficult. “It’s a challenge because the notion of entertainment is evolving rapidly in China as the historical and cultural context of the country is experiencing this notion of modernity,” the New Zealand native explains. “Chinese stories, entertainment, art, music and culture are extremely deeply rooted, but Westerners can bring a new way of packaging it.”

Changing consumer tastes is also an issue for beverage and packaged foods distributor Universal Robina Corp., the No. 1 company in the Philippines.

“People are very busy — they tend to graze rather than eat full meals,” says Lance Gokongwei, CEO of the Pasig City–based concern. “The overall strategy of URC is to build a foundation of a consumer-based company following the trend of a growing middle class whose members are looking for affordable indulgences in their lives.”

In July 2014, Universal Robina paid $606.6 million for Griffin’s Foods, New Zealand’s largest snack-food producer. The acquisition will also allow URC to build a presence in Australia and New Zealand. “This means we can translate Griffin’s into a premium brand for the aspiring middle class in our region,” says Gokongwei, 48.

The past year has also brought two joint ventures — one with France’s Danone, with whom Universal Robina will be making and distributing beverages, and one with Calbee, Japan’s largest snack maker, which establishes a partnership in the Philippines to make potato-based products.

More and more people are looking for the types of affordable, quickly consumed goods the company offers. The next challenge is to expand the number of outlets, such as convenience stores, through which URC distributes its products, and Gokongwei has a plan for that too. “We just have to execute,” he says.