I was driving home the other day from Stanford University — where I work — and turned on NPR. I happened to catch Krys Boyd of Think asking West Virginia University’s Reed College of Media assistant professor Alison Bass, “Who becomes a prostitute in America?” What followed blew my mind. “[It] ranges from women who are paying their way through school . . . to people paying off student loans.” What? Consider me naive, but I don’t think students should be forced to sell their bodies to pay for college. But, sadly, they are.

When I got home, I googled and found brothels that attract sex workers by promising to help them pay off student loans. There are websites to connect rich men with college students who need money. I found a U.K. study that showed 10 percent of students know other students doing sex work. Another study, from Germany, found 7 percent of college students had been sex workers. In the U.S. a website that connects students with “benefactors” claims it has 58,000 women registered in the New York area alone. So, yeah, perhaps Bass was correct to call out tuition and college loans as big drivers of prostitution. Sigh.

It seems the labor market distortions from student debt and tuition are felt throughout our society. Doctors gravitate to niche specialties that pay more to dig out from mountains of debt. Students with big loans are forced to sidestep their chosen careers for a job in, gasp, private equity. In the U.S., student loans are a bigger drain on families than credit cards or auto loans; second only to mortgages. And this doesn’t even speak to the many students who never get to finish college because of the cost.

There has to be a better, less distortionary, way to finance higher education. And I think there is! But it requires some creative thinking and an open mind. Bear with me.

I’m going to make a case for university endowments — and other deep-pocketed, long-term investors — to help finance college education in a manner that minimizes the deleterious effects of its high cost. I’m proposing that endowments take their PE investments — the same ones that they are taking heat over as fees paid to general partners dwarf the tuition assistance provided to students — and redirect that capital into an investment, with similar risk-adjusted returns, in their students. I’ll explain how in a moment. But first, here’s some background.

It’s important to note that college graduates earn $1 million more over their lifetime than people who do not have a degree. According to a 2014 Brookings Institution report, “student debt levels are not large relative to the estimated payoff to a college education in the U.S. Rather, there is a repayment crisis, with student loans paid when borrowers’ earnings are lowest and most variable.” In other words, even with the high price tag, it still pays to go to school. And that’s a good thing. From a financing perspective, we can thus focus our attention on finding new ways to finance education that more equitably and efficiently distribute its cost, future gains and potential losses.

Specifically, I think university endowments should consider investing in their students’ human capital directly and, in turn, participate in their future successes and failures.

Some of you are already rolling your eyes because you know where this is going. Yes, my friends, I am about to suggest, as many others have, using income share agreements (ISAs) and human capital contracts (HCCs) to provide an investor (say, a university endowment) a share in an individual’s future earnings in exchange for up-front investments in human capital (i.e., education). (Student X receives tuition from Investor Y. In exchange, Student X pays a percentage of his or her future income to Investor Y.) But before you click away, please note that the difference in this case and this article is that I’ve spent a career helping the biggest investors on earth, the Giants, actually do these sorts of innovative things. And I think, perhaps naively, that with the right structure they’d really do it.

First, the Giants I know are proactively seeking out assets that will produce decades of cash flows explicitly tied to wage levels and inflation; investing in human capital via an HCC would achieve that. Second, a back-of-the-envelope calculation finds that an investment in students’ future earnings can, without too crazy of assumptions, generate an unlevered 10 percent internal rate of return over 30 years. (This assumes four $20,000 “investments” in a student over four years; graduate salary is $60,000 with a 6 percent growth rate over 30 years; income share is 10 percent over 30 years.) That’s enough to raise the eyebrows of any endowment. Overlay a bit of leverage and you’ve got a replacement for your private equity book (and the fees). Focus only on graduate students, with their higher graduate salaries, and you’d get another big bump up in returns. If we can find a way to get over some of the creepiness of pricing people the way we price companies, I think the Giants would be ready investors in human capital.

Encouragingly, there are a few income-based repayment plans for student debt offered by the government that provide inspiration. They are loan products but are a step in the right direction. Also, income-share agreements are as old as apprenticeships. Even poker players often use ISAs to stake a seat at a table. It may seem utterly distasteful to think that we as human beings can be “priced” in this manner. But we already do it in the form of credit scores correlated to interest rates. If you can wrap your head around long-term investors owning hospitals, parking meters, ports, or elder care facilities, why not this? Why not a share of your student population’s future earnings? Think of this as an investment in our collective human infrastructure or the aggregation of many individuals’ human capital. And if you still find this concept distasteful, ask yourself if you find it more or less distasteful than a student being pushed into prostitution to cover the costs of education? Hmm? Or is it worse than a physics Ph.D. with a job offer from NASA choosing instead to go to work for a hedge fund?

Binding a student to a debt instrument, which is ultimately designed to minimize the risk to the lender, seems to me a complete misalignment between the financing and the underlying asset we are trying to cultivate. An equity-like structure for student financing is more appropriate because equity is generally associated with earlier, riskier investments oriented toward upside and growth. In my view, this aligns more naturally to the payoffs from education. In theory, the investor (i.e., the university) would be highly motivated to produce successful young adults. The externalities would be positive, as we developed a culture of “being in it together.” When human capital becomes investable in this manner, it evolves into something that must be properly nurtured, much like a venture capital firm works with start-ups.

But, Ashby, the cost of capital on the equity is higher than for the loan! Well, that’s true. And the reason is that the investor is taking higher risk. The student has no liability. Similar to backing a start-up, if the investment does not pay off, we lose our money. Even students who drop out would be better off under an HCC structure than with a loan, as they wouldn’t have the benefit of higher wages that go with the college degree. They would simply pay the income share in connection with the investments that had been made, and that share could be considerably less than full student loan costs. Consider the way student loans work: If borrowers default, the government will garnish their wages to the tune of 15 percent until their debt is paid. That’s risk that most students don’t appreciate when building up debt.

HCCs and ISAs simply seek to provide flexibility to students. There’s nothing in the contract that spells out what the graduates need to do with their lives. They get to choose their future. The trade-off for this flexibility is that they share some of their earnings — the highs and the lows — with the investor that paid for their education.

So how do you design such an investment program? There’s actually plenty of precedent out there to help you get comfortable with these contracts and approaches. To be sure, you’d want to avoid adverse selection and onboard as much of a university’s student population as possible. That’s in part why I think starting with endowments as investors is appealing. Some of the recent start-ups that were going on their own toward HCCs — without a big university partner — ended up having to pivot because of these adverse selection problems. I’d also suggest we not repeat Yale’s mistakes from its 1970s experiment with income-share arrangements. That university failed to see such financing as the development of a portfolio of independent equity interests, instead articulating it as cross-subsidization of loans. Yale asked that all members of the class continue paying their share (depending on income) until the loans of the entire class were paid off. The alumni revolted, I think, because this was still conceptualized as a loan. Yale should have built a diversified portfolio of human capital (equity) assets that were independent. In the same way that a VC portfolio has a few big winners, a bunch of average performers and a few failures, so too would a portfolio of HCCs. The big winners will pay more than the others, which will juice returns for the investor. But the assets themselves aren’t linked. All this is to say that although there are big challenges with HCCs, the right program design can mitigate adverse selection and negative effects while offering something new and constructive to students.

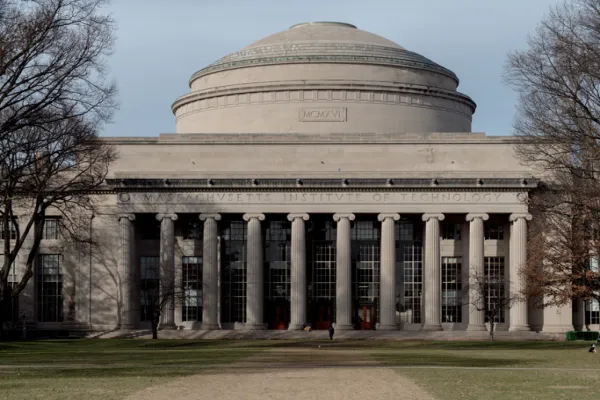

Let me sum up here because this is getting long: Benjamin Franklin once said that an investment in knowledge pays the best interest. What he didn’t specify, however, was to whom that interest needs to flow or how it should be structured. As an educator with affiliations at Stanford, Oxford and the University of California, I find it very disconcerting that the way we finance and repay university tuition today creates such negative consequences for students. I would gladly take my pension and invest all of it in Stanford, Oxford and UC students. And this wouldn’t just be an investment in their human capital. It’d be an investment in a more sustainable human infrastructure.