Active share, a simple measure of the distance between a portfolio and its benchmark, has seen widespread adoption in the past few years as a way to gauge the degree of active management in a portfolio. Many asset managers tout their active share, several leading investment consultants emphasize the measure as a key ingredient for manager selection, and some institutional investors have even gone so far as to embed a high active share requirement in their investment guidelines.

We at AQR Capital Management find that although active share may be a useful means to understand the degree of a manager’s active risk, we see no support — either in theory or in the data — for the argument that high active managers generate better performance.

Active share has gained prominence because its proponents have boldly claimed that it can predict fund performance. Research studies from Martijn Cremers, professor of finance at the University of Notre Dame, and Antti Petajisto, portfolio manager in BlackRock’s scientific active equities group, among others, suggest that investors can improve their performance by more than 2 percent per year simply by selling their low active share funds and investing in high active share funds. Our research, however, shows that the measure’s predictability of manager performance is actually quite weak.

Clearly, to outperform, one needs to deviate from the benchmark. It might be tempting to suggest that the larger the deviation, the higher the alpha. Sadly, that is not how the world works. Being different from a benchmark will likely lead to differences in returns, but there is no basis for predicting why those differences should be positive rather than negative. Large deviations from the benchmark will lead to large active returns in absolute terms, the problem being the sign of those returns! It is also a challenge to explain why active share should work when other measures of activity do not. Tracking error also captures active risk, for example, but nobody claims it predicts performance.

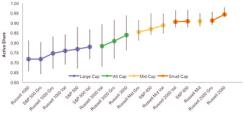

We explored the empirical evidence using the same active share data as the original studies (with thanks to Petajisto for making the data available). A first check of those data reveals an interesting result. The level of active share is highly correlated to the benchmark type (see chart 1). That is, large-cap funds have lower active share than all-cap funds, which in turn have lower active share than midcaps, which in turn are still lower than small caps. Furthermore, even the top quartile of active share of large-cap funds is lower than the bottom quartile of small-cap funds.

Chart 1: Active Share (Average and Inter-Quartile Range) by Benchmark

Source: AQR using data from Petajisto (2013) http://www.petajisto.net/data.html.Data is from 1990-2009.

Click to enlarge

This pattern has important implications for the headline performance results shown in the original — and subsequent — studies purporting to show the predictive power of active share. All that those results say is that small-cap funds had more success beating their benchmarks than did large-cap funds over the sample time period. Given this link between active share and benchmark, more work needs to be done to test the true efficacy of the measure.

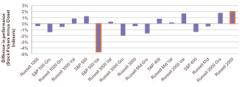

The most obvious way to identify whether active share can identify outperforming managers is to simply compare high and low active share funds within each individual benchmark (see chart 2). Take the S&P 500 (again using data from Petajisto). On average, 356 funds in the sample chose this index as their benchmark. The data show that the performance difference between high and low active share funds is positive — good news for active share — but statistically unreliable. The second-most-popular benchmark, used by an average of 123 funds, is another large-cap index, the Russell 1000 Growth. Here, however, high active share predicts lower performance. Overall, we find that active share predicts higher returns in about half of the benchmarks but predicts lower returns in the other half — hardly an endorsement of active share’s predictive success. Rather than analyze one benchmark at a time, we can also look at the entire universe of funds at once. In doing so, we find that the set of more-active funds — those with relatively high active share within their own benchmark, irrespective of index — generates performance that is statistically indistinguishable from the set of funds that have a relatively low active share within their own benchmark.

Chart 2: Annualized Difference in Performance Between High and Low Active Share Funds by Benchmark

Source: AQR using data from Petajisto’s website; CRSP Mutual Fund Database. Data is from 1990-2009.

Click to enlarge.

The apples-to-apples, within-a-benchmark comparison indicates that active share does not predict performance. Any relationship with performance is unreliable: sometimes positive, sometimes negative and in most places insignificant — about what you would expect from random noise. Once you control for the correlation between active share and benchmark type, there is simply no evidence that active share might help investors choose better-performing managers. So, with no economic reason to expect such a relationship in the first place, the data actually do line up well with theory.

Although active share has no meaningful predictive power for manager skill, it can be helpful in understanding the degree of a manager’s active risk. This information can be useful, most obviously for gauging appropriateness of fees. Fees should be in line with the amount of active risk that funds take, whether you measure it by active share, forecasted or realized tracking error or any other measures of portfolio activity.

Andrea Frazzini, Jacques Friedman are principals and Lukasz Pomorski is a senior strategist at AQR Capital Management , an investment management firm in Greenwich, Connecticut.

Get more on indexing.

This material is the opinion of the manager, is subject to change and has been provided for informational purposes only. It should not be considered as investment advice or a trade recommendation.