The recent sharp decline in oil prices will likely be at the top of the agenda at the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) meeting this Thursday in Vienna. Yet despite this pressure, our research suggests that the underlying economics of production should eventually drive oil prices higher from present levels.

Since August the price of Brent crude has fallen by more than 20 percent, to about $80 a barrel. That comes after three relatively stable years in which the price has hovered in the range of $90 to $110 a barrel. Several factors have triggered the decline. Demand growth has slowed, particularly in emerging markets and the euro zone. Non-OPEC production growth has stayed strong, driven primarily by the revolutionary extraction of shale oil in the U.S. And OPEC production has also increased as Libyan facilities have started coming back online. Meanwhile, there’s growing concern that Saudi Arabia is rethinking its commitment to play a balancing role in world markets.

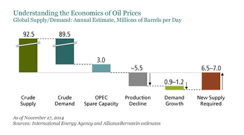

Oil prices are underpinned by the full cost of new production, plus a security premium that is influenced by the availability of spare capacity to surmount potential supply disruptions — like the recent civil war in Libya or the imposition of economic sanctions against Iran. Oil demand grows slowly, by about 1 to 1.5 percent a year. That may not sound like a lot, but producing enough to keep up with demand that’s increasing by some 900,000 to 1.2 million barrels per day (bpd) is no easy task. Unlike most other commodities, oil needs intense investment just to keep production flat, because producing fields decline by about 6 percent a year, or 5.5 million bpd. So the world needs new projects to deliver about 6.5 million to 7 million bpd of new supply just to preserve spare capacity (see chart 1; click to enlarge).

Additional supply from U.S. shale will help meet some of that demand growth. But we believe new investments in ultra-deepwater and oil sands are still needed. According to our analysis, some of these projects require oil prices of at least $80 a barrel to be economical.

Spare capacity matters for these calculations. Saudi Arabia controls most of the industry’s spare capacity, which amounts to about 3 million bpd, according to our estimates. That’s not really a lot, considering that troubles in a major producer like Libya, Iran, Iraq, Nigeria or Venezuela could curtail supply by more than 1 million bpd. It also feeds into the security premium. Consumers are eager to sustain a smooth supply no matter what, and will tend to pay to secure it when capacity is tight — or when there’s a perceived threat to supply. This explains why the oil price spiked in June as ISIS drove on Baghdad. We believe the security premium adds about $10 to the price per barrel on average.

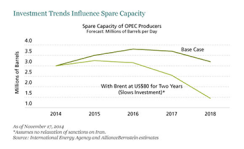

Taken together, all of these factors suggest an equilibrium oil price of $90 to $100. Of course in the short term, if production rises faster than demand, a glut of oil can push prices below this range. But if low prices persist, investment will be suppressed and spare capacity will tighten (see chart 2; click to enlarge). Then, prices would likely begin rising again.

Short-term swings in demand and the phasing in of new supply can cause the price to fluctuate. In recent years Saudi Arabia has adjusted production to keep the market balanced and prices fairly stable. Saudi officials recently suggested that they might no longer be willing to cut supply to balance weaker demand and U.S. supply growth. This may be a negotiating stance ahead of the big OPEC meeting tomorrow, or it could reflect a desire to reduce investment by non-OPEC producers.

If OPEC moves to curtail production in the coming months, Brent prices could rise back into the $90 range fairly quickly. Alternatively, a Saudi tactical shift could keep prices lower for longer — but not forever. If $80-a-barrel oil is sustained for a year or more, we think the impact on investment will be significant, and the seeds of a future spike in oil prices will have been sown. It’s only a matter of time before the market begins to recognize this — and starts to push oil prices back up.

Kevin Simms, based in New York, is chief investment officer, global and international value equities, and Jeremy Taylor, based in London, is a senior research analyst and portfolio manager, both at AllianceBernstein.

See AllianceBernstein’s disclaimer.

Get more on macro.