In early August, CaixaBank, Spain’s third-largest lender, made a purchase that looks positively nostalgic: voluntary carbon credits to offset its greenhouse gas emissions.

The credits, validated by the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) established in the Kyoto Protocol and now overseen by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), were generated from a wind farm and a natural-gas plant in Colombia. They’re meant to offset the 658 metric tons of carbon that Barcelona-based CaixaBank produced through its power use, water consumption, waste management and employee travel last year.

For companies seeking to shrink their carbon footprints, offsets have fallen out of favor in recent years. It’s a far cry from 2006, when “carbon neutral” was the New Oxford American Dictionary’s Word of the Year, and actor Leonardo DiCaprio, the Rolling Stones and media baron Rupert Murdoch boastfully climbed on the bandwagon. Google pledged to go carbon neutral in 2007, the Walt Disney Co. announced the same commitment two years later, and General Motors Co. followed suit in 2010.

Is the CaixaBank purchase a quaint throwback or a sign of more activity to come? Advocates remain hopeful that carbon offsets will soon see a resurgence. Others say corporate clean energy initiatives are increasingly skipping carbon offsets — and that this trend is a good thing.

Offsets began losing their shine after the global financial crisis blew up talks about establishing a mandatory carbon market framework in the U.S. Also, the failure to hammer out a deal on a binding international market at the 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen (a meeting of the parties to the UNFCCC) distracted and disillusioned many would-be voluntary offset buyers (see also “Climate Change and the Years of Investing Dangerously”).

Hugh Sealy, the St. George’s, Grenada–based chairman of the CDM’s executive board, says a new global carbon agreement at the next U.N. Climate Change Conference, scheduled for December 2015 in Paris, could throw carbon offsets back into the limelight. Don’t bet on it, counters Brian Jones, a Concord, Massachusetts–based senior vice president at environmental consulting firm M.J. Bradley & Associates. “I feel like offsets had their day, and if they were going to take off, we needed a carbon market [in the U.S.],” Jones says. “It’s almost like the dialogue has moved beyond them.”

There’s evidence to support this view. In 2013 the global value of the voluntary carbon market was just $379 million, according to Ecosystem Marketplace, a research initiative of Forest Trends, a Washington, D.C.–based environmental nonprofit. That’s a 52 percent drop from the $789 million peak in 2008, when Ecosystem Marketplace began publishing its annual report on the market.

The initiative has drastically scaled back its growth predictions: Last year’s report stated that the voluntary carbon market could reach between $1.6 billion and $2.3 billion by 2020, whereas the 2014 publication slashed that forecast to anywhere from $900 million to $1.8 billion.

The smaller numbers reflect the fact that “people have become more realistic about where the market is right now,” says Allie Goldstein, an associate with Ecosystem Marketplace’s carbon program and a co-author of the 2014 report. In 2013 clean-energy developers continued to see dampened demand for the voluntary credits their projects were generating, she adds.

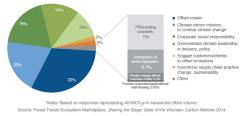

Offsetting Purchases: Voluntary carbon offset market share by buyer motivation, 2013

It doesn’t help that companies have been moving away from carbon neutrality as a way to assert their green credentials. “Corporations are getting more intelligent about climate change risks, and they’re doing more internally,” M.J. Bradley’s Jones says. Rather than reach for offsets, he explains, businesses are tempering their greenhouse gas emissions and reporting on that progress to investors and to carbon disclosure groups such as CDP (formerly the Carbon Disclosure Project). “They’re seeing that those moves are cost-effective, that they provide bottom-line benefits,” Jones says. “Offsets are really designed, in my opinion, as a last resort” (see also “Why Investors Should Care About Climate Change”).

Tanya Weekes, a portfolio manager at Climate Change Capital, a London-based asset manager that helps develop clean energy projects and sells the resulting carbon offsets to corporate and government buyers, notes that her firm has seen the supply of voluntary offsets far outstrip demand during the past few years. “You can still usually sell them at a profit, just not enough of a profit to create a new business around it,” Weekes says.

However, the U.N. is still pushing voluntary offsets through the CDM, probably because it has invested time and resources in the mechanism, which facilitates the sale and trading of its certified emission reduction (CER) offsets. Launched in July, the UNFCCC’s Climate Neutral campaign calls on U.N. staff and their families to voluntarily purchase CERs to compensate for their emissions. Eventually, the campaign will be expanded to engage companies and regional and civic governments on carbon neutrality.

Adam Bumpus, an assistant professor of environment and development at the University of Melbourne, agrees with the CDM’s Sealy that the upcoming Paris discussions might be a turning point for carbon offsets. “I’m virtually positive there will be a global agreement on climate change with legally binding targets, including a new market mechanism,” he says. “That could really invigorate this market.”