KKR recently took a trip to Ireland to visit our local partners as well as to meet with macroeconomic players, government officials and business leaders about the state of the country’s economy. From almost every vantage point, we believe the Irish economy is moving in the right direction, though plenty of rebalancing remains.

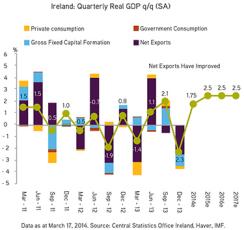

Our biggest takeaway from the visit was that Ireland’s story has moved beyond being just one of financial services restructuring or improving exports. Somewhat to our surprise, economic momentum seems to have spilled over to the domestic consumption market. How strong is this force? Well, one executive indicated that with job additions running 3 percent year-over-year, out of the companies he surveyed, 40 percent are likely to increase wages by 3 percent during the next 12 months. Meanwhile, government employment has become less of an economic drag, with the public payroll shrinking to 295,000 from 325,000. We believe Ireland’s government debt likely peaked in 2013 at 123 percent of GDP, and it is running with nominal GDP greater than nominal interest rates, which is key to overall long-term fiscal rebalancing.

An important message we took from the folks on the ground in Dublin is that going forward we should expect a different financial services landscape in Ireland. On the one hand, we are looking for further consolidation of the retail deposit-taking business by just a few players. In the end, we expect somewhat of an oligopoly structure in Ireland where a few tightly regulated, low-leveraged retail banks enjoy leading market share positions.

On the other hand, we are looking for a more disaggregated wholesale banking market, which bodes well for third-party, direct-lending businesses. Key to our thinking are the following considerations: First, many weakened local banks are not likely to get the necessary ratings upgrades required to be competitive in an environment of oversight by the European Central Bank. Second, in addition to those in Sweden, many leaders throughout Europe have agreed that dispersing credit risks — if done properly — is a better solution than leaning on the bank-heavy lending model. Third, relying on cross-border lending, as has been the case in Europe, also has significant shortcomings, given the high correlation risks.

Although we do not think the U.S. private credit lending model can be transmitted overnight to Europe, we do think macroeconomic tailwinds have been blowing much stronger in favor of outside, third-party capital than in the past.

Economic trends are, for the most part, looking positive, yet Ireland still has a few macroeconomic factors to take into consideration. Beyond the two-tiered economy, the mortgage credit market is still developing poorly, despite an improvement in the job market. First, according to one source, 75 percent of the defaults have been from mortgage customers with jobs. Moreover, debt-to-income ratios are manageable at 28 percent.

Second, the lending market is still clogged, particularly on the retail side. In fact, our research indicates that 55 percent of all housing market transactions in Ireland in 2013 were done in cash.

Third, the supply side of the real estate market is also stagnant, with many unable or unwilling to sell at present prices. This characteristic is particularly evident in Dublin, where 40 percent of recent transactions have been estate sales. Short supply was a key driver of the 15 percent surge in Dublin prices in 2013, compared with the 40-basis-point decline outside of the capital, but the situation is unlikely to persist. About 15 to 20 percent of residential mortgages remain in arrears, and whereas we expect that many of these cases will resolve themselves as the market improves, others will become short sales.

Our overall view is that we are entering a new phase in Europe with peripheral economies like Ireland leading the pack. If phase one started in 2010 with weakness in the periphery, it ended on July 26, 2012, with European Central Bank president Mario Draghi uttering the words “whatever it takes.” If we use Ireland as a proxy, sovereign yields presently are at or below precrisis levels.

Phase two, which seems to be coming to an end, has been centered on restructuring and austerity. The third and final phase of Europe’s economic recovery, which we think will play out over the next few years, should center on what we call the normalization process: GDP would move back toward long-term growth of 1.5 to 2 percent, inflation would remain low, and consumption would slowly recover as fixed investment and exports rebound from trough levels. If we are right, then our marginal thesis trade likely means more equity market catch-up for Europe.

Henry McVey is head of KKR’s global macro and asset allocation team.