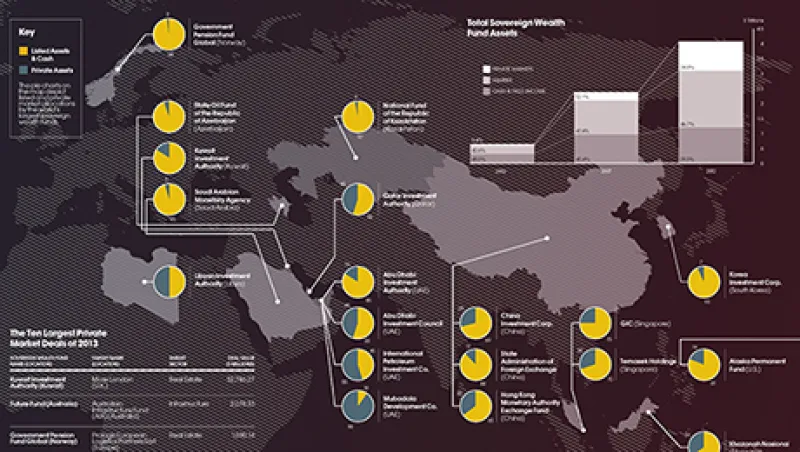

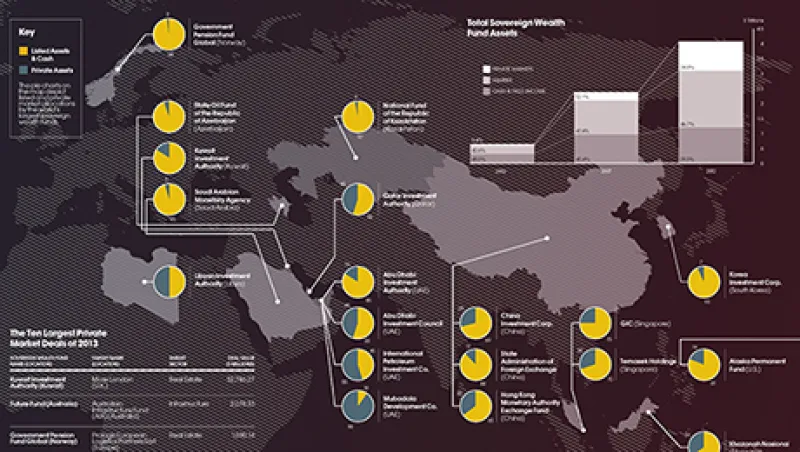

The World’s Largest Sovereign Wealth Funds Go Private

Sovereign funds are turning to private market investments to diversify portfolios and boost returns.

Georgina Hurst

September 22, 2014